Editor’s note: The names of some individuals have been changed for privacy and identity protection.

Like hundreds of other Central Oregon parents, Anthony Harper drops his 9-year-old son off at the bus stop and then leaves to go about his busy day with Zoom calls, chores and errands. Unlike most parents, however, Anthony is homeless. For the past four years, he and his son have split time between shelters and their small RV in various locations in and around Central Oregon where they can feel safe and seek refuge.

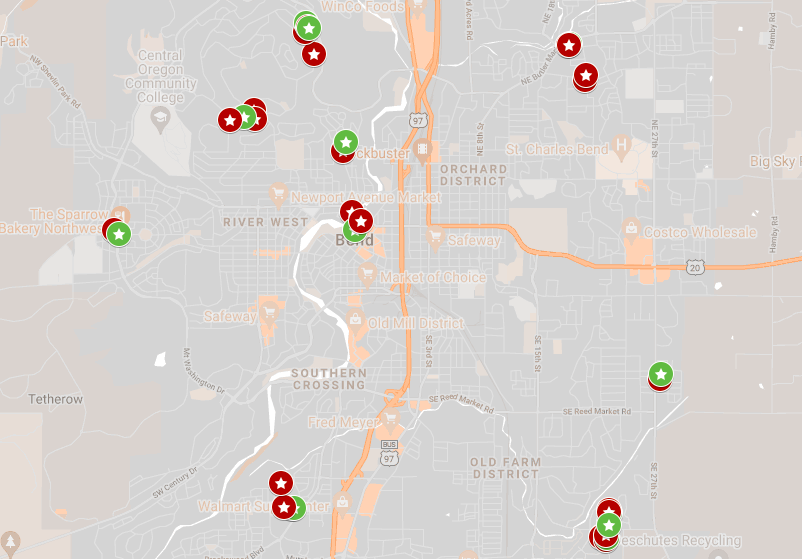

Anthony is one of a growing population of homeless in Central Oregon. According to the most recent Point in Time count (PIT), an initiative that counts the homeless population on a single night in winter, the number of homeless has grown in Deschutes County to 1,098 individuals—an alarming 13 percent increase from the previous year. Pair that with another 12 percent increase the previous year, and the city has seen a whopping 25 percent increase since 2019. These figures are likely low as well, according to Bend City Counselor Megan Perkins. “It’s not perfect. They take numbers on one night and there are a lot of people that are not reached,” she said. “The likelihood is that it’s much larger.”

The growth is visible. The number of pitched tents appears to have grown exponentially in the area over the past few years, with ramshackle camps sprouting up in vacant lots, deserted streets and on/off ramps around the city. Just outside of town, along areas such as China Hat Road, dilapidated RVs and trailers dot the forest roads where houseless individuals are living out of their vehicles. The numbers of tent camps and vehicles are difficult to estimate, but Anthony Harper says he’s seen the forest roads transform over the past few years. “It used to be you’d have to walk a good distance to find anyone,” he said. “Now, you’re surrounded by people.”

Our Neighbors without Walls

According to Colleen Thomas, Deschutes County Homeless Services Coordinator and Chair of the Homeless Leadership Coalition, which serves Deschutes, Crook and Jefferson counties along with the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, homelessness is very individualized as everyone has their own reasons for being homeless. “I’d be lying if I said there weren’t individuals in our community who do not struggle with either mental illness or substance abuse,” she said. “It’s a large percentage of the homeless population. Chronic homelessness and mental health or substance abuse go hand in hand.”

However, Thomas is also quick to debunk several stereotypes of the homeless, including that many are transient or just passing through town. On the contrary, most of the individuals are our former neighbors and classmates, according to Thomas. “Eighty percent of the people surveyed from the most recent point in time (PIT) count were last stably housed in Oregon,” she said. “When we look at chronic homelessness, it’s individuals who have been in our community for years.” Additionally, many individuals who are homeless are employed. “We hear a lot where community members think there are jobs available and wonder why they don’t work, but the reality is that many already do have jobs,” she said. “But ‘affordable housing’ does not always address what people can really afford, nor does it account for wait lists and other variables.”

Anthony Harper has experienced this himself. A Bend resident off and on since 1999, he previously worked as a skilled machine operator and prior to that had a photography business working with clients such as Hoodoo Ski Area. Due to financial struggles and unforeseen hardships, however, he was not able to keep up and eventually was forced to move into the RV. “I made close to $40,000 but still couldn’t find housing,” he said. “People don’t understand. You need rental history; you need IDs and letters of recommendation. You need insurance. And where do you wait while you’re on a wait list?” Eventually, after losing hundreds of dollars in application fees and getting nowhere, Harper says he gave up and turned back to the RV. Since COVID, he’s gone back to school full time and will be graduating from OSU this winter. Upon graduation, Harper says he’s done with Central Oregon. “Once I graduate, we’re out of here,” he said.

The Need for More Services

Affordable housing and financial struggles are primary reasons for many individuals being homeless, but Bend City Counselor Megan Perkins says the lack of services is a close second. “There are not enough treatment programs in Bend, not enough beds in the shelters and not enough mental health programs,” she said.

John Lodise, the Director of Emergency Services at Shepherd’s House, which provides emergency services for men, women and children in Bend and Redmond, said the demand for shelter continues to rise. “We now have more capacity than ever before but we continue to see more requests coming in to meet that demand,” he said. Lodise noted that this past winter, between Thanksgiving and March, 371 individuals utilized the Bend Shepherd’s House shelter and 106 stayed overnight at the Redmond facility.

Colleen Thomas agrees that more effort needs to be put toward service providers and acknowledges the current gap between policy and funding and actual execution. “Elected officials can throw money and policy at the issues all day long, but we need to think more about how we can support these projects with staffing and boots on the ground,” she said. “All of our service providers are at capacity and stretched thin.”

Shepherd House’s Lodise says the real challenge is with staffing and figuring out what is required to effectively provide the services needed to the homeless on the streets. “How many folks does it take to work alongside these individuals [in camps]?” he said. “We don’t know the answer to this, but it’s a lot. It’s hard work, and you have to find people who are committed to doing the work, which is difficult.”

The strong growth of the homeless population has forced the city to take notice and it has responded in several ways. According to the homelessness page on the city website, “The City of Bend is working with public agencies and community partners to support homelessness solutions for our community. This includes finding ways to keep people in their homes, provide temporary transitional housing and increasing the availability of affordable housing.”

Closing the Gap

Realizing the gap that exists between the policymakers and the service providers doing the work, the city established the Emergency Homelessness Task Force (EHTF), which began convening in early summer 2021. The group currently consists of a mix of government employees from the City of Bend and Redmond, the county and fifteen service provider liaisons. According to a City of Bend website, the group was established “to bring the most informed minds on houselessness together to inform both the city and the county on collaborative opportunities with countywide resources and to develop actions toward ending houselessness in Deschutes County including interim actions to address real-time needs.”

City of Bend Counselor Megan Perkins serves as the council liaison on the EHTF, and said she hopes the combination of government and service providers will bring a more unified front to the fight against homelessness. “One of the things we didn’t want to do was just barrel ahead without getting input from the people doing the work,” she said. “These are the people that respond most to the homeless in the community.”

Carolyn Eagan, who serves as the City of Bend’s Recovery Strategy & Impact Officer and EHTF member, said the task force is first prioritizing three main areas: creating authorized encampments, or managed camps, within the city of Bend, developing permanent supportive housing and formalizing emergency protocols to keep people safer during extreme weather events.

Eagan heads up the subcommittee to find a more permanent location for the managed camps. “We need these immediate authorized encampments,” she said. “The current camps are not safe places for individuals to camp.” Eagan said the target is to launch one camp before the winter season sets in to serve as a pilot, take the learnings and then apply those learnings to one-to-two additional managed camps. She said the camps would cost approximately $350,000 to $400,000 per year to run, which does not include the additional services by those on the ground. The city has $1.5 million in funds slated for the initiative while the county has $750,000 earmarked, with potential for an additional $750,000.

Eagan stressed that the solution is meant to be temporary until more permanent, affordable housing is built. Until then, the managed camps will provide a stable address for individuals. “It’s easy to become disenfranchised when you lose your home because you lose your address and everything attached to it,” she said. “But if we can find a semi-permanent location and give them an address, we can get them an ID, get them back on OHP [Oregon Health Plan] and get them treatment if needed. There’s a lot of concrete value in having an authorized encampment that’s properly managed.”

Permanent supportive housing (PSH) is the second priority being worked on concurrently by the group. Colleen Sinski, program manager at Central Oregon FUSE, a non-profit established to address frequent users of health care and law enforcement, is leading the initiative and subgroup for the task force. In a recent EHTF meeting, Sinski stated the goal is to “combine affordable housing with on-site services—health care access, substance abuse treatment, community programs—to meet the needs of folks who are the most vulnerable in the community.” She stressed the need for long-term funding for the project for it to work. “It’s not just funding the operations,” she said, “but how do we have 10 to 15 years of secure funding so that the residents have the support they need to be successful over the long term,” Sinski said funds would be pulled from dozens of sources and the group recently put out an RFP for consulting and development.

The third priority is developing and formalizing the emergency protocols to address real-time needs for the homeless during heat waves, fire season, cold and inclement weather, and other unforeseen or unpredictable circumstances. “What are we doing when the smoke or the heat don’t go away?” said EHTF member Carolyn Eagan. “We need to be formalizing this process to provide relief for folks that don’t have a place to go.”

According to the city webwsite, the EHTF has an aggressive timeline and hopes to have strategy and plans in place to begin executing the initiatives in winter. Eagan said the group is making strides but still has a long road ahead. “We’re making progress,” she said. “It’s been the easy progress so far, but the next few months are going to be the difficult progress.”

Still, the group is feeling optimistic. Deschutes County behavioral health homeless services coordinator and EHTF member Colleen Thomas said she feels Bend is finally going in the right direction. “I’ve been doing this work for a long time, and when we talk about homelessness and addressing it, there’s usually a buzz around the winter months or the holidays, and then it usually fizzles out,” she said. “But now it’s not fading anymore. The community is opening their eyes to the problem.” Thomas said she believes part of it is the shift in elected officials who are now looking to create solutions. “It’s a bumpy road, and there’s always room for improvement, but we’re heading in the right direction.”

How to Help

While the city and service providers strategize for both short-and long-term solutions, citizens can also lend a hand—or in some cases, just a smile. “Just greet someone and smile,” said Anthony Harper. “Even though we might not smile back it doesn’t mean we hate you. We’re just having a hard time.”

Colleen Thomas said the easiest and most impactful action the community can make is to treat all individuals with dignity and respect. “It seems very basic but it goes a long way,” she said. “The second thing people can do is educate themselves on the topic and the resources. And lastly, volunteer—serve meals, educate, advocate; help in any way.”