Poet Jarold Ramsey’s connection to the land of his youth eventually brought him back home.

Jarold Ramsey grew up on a farm perched at the edge of a canyon that connects two communities and two worlds. His home sat between the tribal town of Warm Springs and the farming community of Madras. This proximity to both cultures has shaped Ramsey’s life and his art ever since.

Recognized as one of Oregon’s literary legends, Ramsey’s poetry is influenced by the land and the people that shaped his earliest memories. He calls canyons “the memory of our landscape,” and has spent his life exploring the layered recesses of a collective cultural memory that is deeply linked to the land. His award-winning poems and short stories tapped into Ramsey’s own deep connection to the land of his youth and his reverence for traditional native culture.

The farm where his family made their home had once been a way station for bands of Wascos, Warm Springs and eventually Paiutes who lived on the Warm Springs Reservation. As they traveled to and from the Ochoco Mountains to dig camas bulbs and hunt, they left traces of those journeys and clues to a nearly forgotten history.

“Every time my dad would plow the field, my brother and I would be right there to pick up Indian artifacts,” Ramsey said. “That kind of cemented the connection with the Indians. I was aware that there was a dimension here that went way back, long before we were here.”

and their stories that, half-forgotten, nearly dead

for lack of telling, seem still to echo

my own voice along the rimrock . . .

In Ramsey’s youth, Central Oregon remained largely isolated from Portland, cut off by the steep walls of Mill Creek canyon. The Deschutes River had yet to be dammed. Change, though, was coming rapidly. By 1948 the Mill Creek Bridge opened what would become Highway 26 and the North Unit Irrigation project was completed, bringing a reliable source of water to Jefferson County farmers. Irrigation increased the value of the previously drought-prone land. Ramsey’s father, a dry wheat farmer, opted to cash out. He sold the farm, but kept the family home, and purchased an old sheep ranch to the east. They renamed it Sky Ranch, and switched to raising Hereford calves, work that Ramsey enjoyed. Meanwhile, he and his older brother Jim began pioneering climbs at Smith Rock and summiting Mount Jefferson, cutting unique trails in life.

Pulled between a life working Sky Ranch and the pursuit of language, Ramsey finally enrolled at the University of Oregon. His interests began to lead him away from the high desert. Ramsey earned a Ph.D. from the University of Washington, and in 1965 accepted a job teaching his specialty, Shakespeare, at the University of Rochester in upstate New York. He and his wife Dorothy, also from Eastern Oregon, departed for the other side of the continent where they raised three children and remained for thirty-five years.

Absence, however, made the heart grow fonder. Distance ignited a steady longing for the canyons of his youth, and for Sky Ranch. A friend in Rochester introduced Ramsey to the work of Oregon’s premier poet, William Stafford, whose descriptions of areas dear to Ramsey spurred him to capture in verse his own memories. He published his first book of poems, Love in an Earthquake, in 1973.

I close my eyes and there we are, you and I,

next summer maybe, in a humming meadow

by the boulder-rolling creek the Indians called Why-Chus

By now, Ramsey was drifting away from Shakespeare.“Back there in Rochester, with the isolation and homesickness, I began to delve into that part of what I thought was a neglected heritage,” Ramsey said. He recognized that “this was part of the American literary heritage,” one that was almost entirely ignored, “and yet there was wonderful material there to be read and enjoyed and celebrated.”

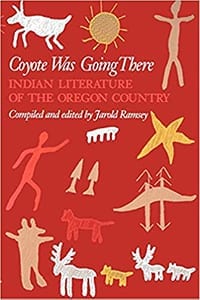

Traveling back and forth between Oregon and New York, Ramsey began to explore a new region of scholarship and to prepare a new book. He met with Warm Springs women including Alice Florendo, a Warm Springs tribal member who was raised on the reservation and managed to gain an education when few other women did. Florendo shared a few still-untranscribed stories from the Wasco oral tradition that had been handed down from generation to generation but never put to paper. Florendo also introduced Ramsey to Verbena Greene, another tribal member, who Ramsey called “an ambassador for her culture to the Anglo culture that was across the way.” Greene translated her stories as she told them to Ramsey, who included these rare tales in his groundbreaking Coyote Was Going There: Indian Literature of the Oregon Country, first published in 1977.

“My main concern was to bring examples of the original material, as transcribed, into the mainstream. But also to get opportunities for young Indian writers to be read, taught, and understood.” He wasn’t the only one interested in connecting with this history. A revival in Native culture was unfurling around him. “After that, I sensed there was a possibility to help create a new academic field, and that was Native American literature,” said Ramsey.

Warm Springs writer, and previous Oregon Poet Laureate, Elizabeth Woody came across Coyote in her late teens. Her family had heard the Wasco and Wishram stories before, “but nobody was telling them in my family directly,” Woody said. Now she could go to a book and not just read them, but believe them. “Jarold stayed true to the stories, and to their origins and sources. He wanted his scholarship to be part of something that would last.” And it has.

Indian, flat on your back in this cave

you made what I would, a prayer to your gods:

a sign to your people you were here

but left. I follow you into stone.

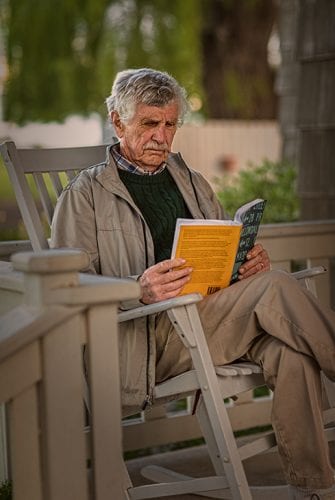

“Coming back into the canyon after a year’s or even a season’s absence is like rediscovering a fertile part of your mind that you’ve lost touch with,” Ramsey wrote in an essay titled The Canyon, included in his book New Era. In 2000, after retiring, Jarold and Dorothy returned to the same house where Jarold grew up, along the basalt rim of Agency Plains, which Dorothy calls his “other ‘spiritual’ home.”

Collections of historical and anecdotal writings followed. He and Dorothy co-authored a book on the life and poetry of a rebellious Irish priest, and Jarold’s poems of recent and old appeared in his book Thinking Like a Canyon.

Having returned to his sacred canyons and Sky Ranch, Dorothy said “Jerry was ready to give back, thus his interest in helping to preserve the history of the area.” Ramsey today serves as a director of the Jefferson County Historical Society, and publishes their journal, The Agate. His latest book, Words Marked by a Place: Local Histories in Central Oregon, arrived in 2018.

As a scholar, Ramsey devoted decades to collecting and publishing Oregon’s Indian stories. Kim Stafford, Oregon’s newest Poet Laureate, has known Ramsey since his father William befriended Ramsey in the 1970s. “Jerry grew up working with cattle and crops, and wandering, camping, fishing, climbing spires for the long view,” Kim said. “He is placed in Central Oregon, reading the history and living seasons of the land like a book of entrancing mysteries. He is our Shakespeare of that wider view from across the mountains.”