A Sisters ranch is poised to culminate the decades Kathy Deggendorfer has devoted to fostering an arts economy for Central Oregon.

Inside one of Oregon’s last remaining round barns, hand-built nearly a century ago on a Sisters ranch dating back to 1850, Kathy Deggendorfer is looking up at the elegant slope of the conical roof, supported by a swirl of wooden beams. She marvels at the craftsmanship, speculating about the Old World design origins of the space where horses had been trained for decades. A square opening cut into the wall frames a snow-dusted Black Butte, one of a swath of surrounding peaks. Beyond that, a grove of cottonwoods, some of the oldest east of the Cascades, rustles in the breeze. Whychus Creek winds by, singing its liquid song.

Along the creek, about a dozen more 1930s structures stand as sentinels to that era and make up what is called Pine Meadow Ranch. There’s a bunkhouse, caretaker’s cottage, woodworking sheds, tack rooms and a home designed by one of Oregon’s preeminent architects, Ellis F. Lawrence, the mind behind a score of historic buildings around the state, such as the University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in Eugene.

Relatively few in Central Oregon may know of Pine Meadow Ranch—yet. The 260 acres was ranched, farmed and beloved for nearly a half-century by aviatrix and rodeo stalwart Dorro Sokol, who died last year at age 90. With riparian stretches close to town being scooped up for development, Deggendorfer swooped in and bought it in November to preserve the land, the views and historic buildings, and with the hope of creating a center for exploration of the arts and sciences through the lens of life on a working ranch.

This vision builds on her three decades of shaping the cultural life of the region, from grassroots work in the early days of the Sisters Folk Festival and the Sisters Quilt Show to supporting arts, education, environment and social services in surrounding counties and around the state. Hundreds of these efforts have been funded through The Roundhouse Foundation, which she began in 2002 with her mother, Gert Boyle, known as “one tough mother” from ad campaigns for her company, Columbia Sportswear. (The 94-year-old lives in Portland and has had a longtime affinity for Central Oregon.) Their goal has been to help celebrate creativity, particularly efforts in which artists serve as positive role models and mentors for children, and to create a new arts-driven economy for Central Oregon. With the addition of Pine Meadow Ranch, Deggendorfer is poised to take her vision to a new level.

“I thought, ‘What can we manage and what can we do here?’” she said, strolling the ranch in black boots, her hands in the pockets of a Columbia barn jacket. “I was not willing to see the loss of the view-scapes and the loss of agriculture. I don’t really need to take on this whole other project at 67. I could be a person who plays bridge and golf, but I just can’t. It’s just not right. I want to make a community that we want to live in, and if it’s done in the right way, the rest of the country might come along.”

For her, simply complaining about things is not an option.

A Creative Vision

Throughout her life, Deggendorfer, an accomplished painter, has found that the most inspiring discussions, and the most creative problem-solving, happen when artists and scientists of seemingly disparate disciplines come together to think and work. As she began formulating her vision for Pine Meadow Ranch, she wanted to look at potential models of the concept, but she also wanted others’ perspectives, too, so through The Roundhouse Foundation, she awarded scholarships to eighteen artists for residencies around the nation and abroad. “I chose working artists who are strong-willed, rather than someone who might try to say what they think I’d hoped,” said Deggendorfer.

The artists reported on their experiences, which helped Deggendorfer crystalize a vision for Pine Meadow Ranch. Her dream is to foster a place to connect the arts and sciences with the crafts and skills integral to ranching life: managing livestock, growing crops, preserving food, training horses and dogs, doing leatherwork, woodwork, glasswork, metalwork, ceramics and textiles, painting, photography, music, managing and enhancing Whychus Creek, riparian study, sustainable energy, recreation and social events.

“It’s about honoring that can-do, gotta do-it-yourself spirit,” said Deggendorfer.

For now, it remains a vision. In the short term, her focus is on inviting artists to do individual residencies on land zoned for agricultural and forest uses. “We don’t know what it can be, because we’re honoring the land-use laws and working diligently with the county to see what we are allowed to do, what we can do and how we can work with them to achieve the goal,” she said.

Preserving the working ranch would fit synergistically with a new creative space emulating the agricultural history of Sisters. It would be easily accessible to the community, a ten-minute walk for Sisters schoolchildren coming to the ranch for historical tours, and for artists to contribute to village life, too.

“A farm is a place where things happen—things are grown there beyond food,” she said. “There is a sense of community and thought, such that someday the next cure for whatever ails might come out of an author meeting with a scientist and a woodworker, and saying, ‘Did you ever think of this?’ And it sparks a whole new idea.”

For instance, she pointed to Finland’s Aalto University, which is gaining global awareness of a new environmentally friendly manufacturing process for making textiles. The multidisciplinary science and art community emphasizes that new opportunities and products require open collaboration across organizational and national boundaries.

Like the celebrated, visionary Fab Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which lets anyone design and execute small-scale manufacturing digitally and cheaply, the ranch could offer myriad opportunities, from environmental study to learning songwriting or painting from a resident artist.

“Sisters is a perfect place for this because we have a terrific brain trust and philanthropic community that wants to stay engaged, share what they have and create a place for young minds to grow,” she said.

Back at the Ranch

Since buying the ranch, Deggendorfer and her husband, Frank, have focused on cleanup, salvaging whatever is useful or speaks to its past, from an old forge and branding equipment to a vintage sleigh and enamel cookstove. A monitor-style barn is made of lodgepole beams harvested from the property and has floors of Douglas fir from a nearby stand, now gone. The cat’s-eye pattern of the wallboards was designed by nature—the sweating of the hay stored in the loft. Those who’d gone to house concerts there years ago had described the acoustics of the space, above the adjacent cattle sorting-pens and squeeze shoots. “It was like being inside a guitar,” said Deggendorfer.

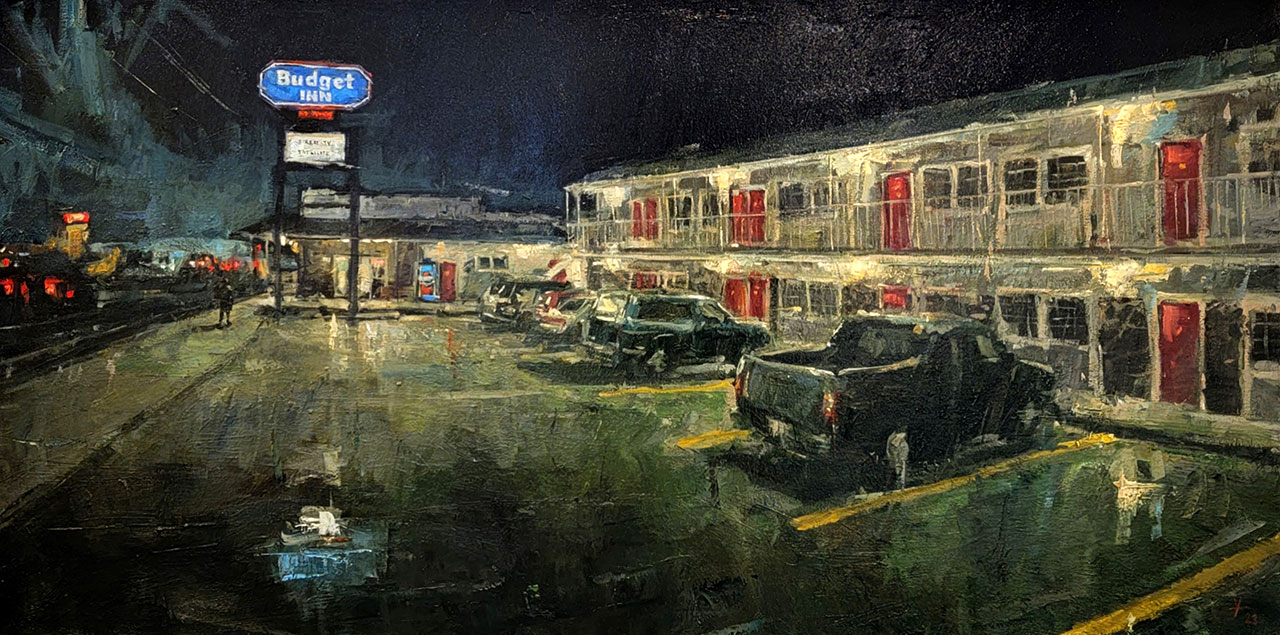

She hopes that in the next few years she will be inviting scientists, woodworkers, ceramic artists, painters, chefs and authors to the ranch for residencies and to join locals, exchanging ideas and creative thought. The concept is an extension of her 2014 exhibit, “Painting Oregon’s Harvest: The Art of Kathy Deggendorfer” at the High Desert Museum, which is now traveling to museums around the state. For that show, Deggendorfer visited working farms, fisheries, cherry, pear and apple orchards, vineyards, Bandon cranberry bogs, and ranches in Central and Eastern Oregon, depicting the beauty and bounty of Oregon-grown food.

“All that study I did is coming full circle,” she said. “It’s not just an art project anymore. The ranch is the opposite of the virtual world, it’s about whatever the body needs and sustains it. How do we honor this place where we are, and how do we not defile this place?”

One Tough Family

Transforming a ranch into a new-styled center for the arts and sciences would be daunting to most people, but Deggendorfer isn’t most people. Those close to her point to a personal history that has primed her for it.

In 1970, when she was 19 studying at the University of Oregon, her father, Joseph Cornelius “Neal” Boyle, died suddenly of a heart attack at age 47. Her mother, a 46-year-old housewife with no business experience, took his place at the helm of Columbia Sportswear, a small and financially struggling outerwear manufacturer that her father had founded in Portland.

Deggendorfer’s younger sister, Sarah “Sally” Bany, said this was a formative moment for all three children. “Mom jumped into the business, and we are all seeing mom doing that. One day you’re this, and the next day something like this happens, and you’ve just got to go for it,” she said. “It’s ingrained in all of us.”

Many expected Boyle to fail, but with her son, Tim Boyle, now the company’s president, CEO and director, they turned it into a leading global retailer of outdoor apparel, footwear and equipment with sales of nearly $2.5 billion last year. The ads featuring Gert as “one tough mother” made her an industry icon, but Deggendorfer said her childhood memories reveal her mother’s true self. “Employees would come to her strapped for cash, needing money for rent or to have their teeth fixed, and even though she didn’t have any money at all, she’d give them money or somehow take care of them, knowing they’d pay her back. She is a very generous person and has a lot of empathy for people.

“That persona of a tough mother, she’s the opposite of that,” she said. “She’ll definitely tell you what she thinks and is not going to take guff from anyone, but she’s protective, empathetic, caring … and taught us [children] all to be.”

Gert Boyle’s book, One Tough Mother: Taking Charge in Life, Business, and Apple Pies, chronicles her journey. She wrote it with Kerry Tymchuk, director of the Oregon Historical Society.

He said, “What Kathy has done for Sisters, turning it into a hub for artistic, creative minds is remarkable, and [Pine Meadow Ranch] is another step down the road of saving an architectural treasure and turning it into something to benefit the region. The fact that her mom is still going strong at 94 is just a little hint of where she gets it. Kathy’s just a force of nature, with a wonderful, self-deprecating sense of humor—she takes her vision of what she wants seriously, but doesn’t take herself seriously.”

In that vein, Deggendorfer quipped that Gert’s spirit may have “skipped a generation” to Deggendorfer’s daughter, Erin Borla. The 38-year-old of Sisters spearheads Columbia’s ReThreads program, which encourages customers to bring in their used clothing to be recycled into fibers for new products such as insulation, carpet padding, stuffing for toys and new fabric, diverting tons of waste from landfills. One of the barns at the Pine Meadow Ranch is also a temporary staging area for the company’s end-of-season coats, boots and other sportswear, which is sorted and delivered to nonprofits.

Columbia’s chairman of the board, who still works daily at her office in Portland, reflected on what shapes one’s work.

“As life goes on, you really think, ‘This is what I’d like to do,’ but I don’t think it should ever be written in stone,” said Boyle. “Things present themselves. I took over Columbia and that certainly was not in the plan, for my husband to die and I’d have to take over, but things present themselves, like the new ranch that Kathy and Frank bought. They were thinking about doing something like that, and the opportunity presented itself.”

At the ranch, the round barn mirrors a round house for which the Deggendorfers’ foundation is named. Kathy recalled that growing up, her family had a small house in Lincoln Beach, and Neal Boyle would tell his children they could wander no farther than the round house. “It was that thing that Dad would say to us kids: ‘Run to the round house! They’ll never corner you there!’”

All these years later, it seems she’s still listening.