As a helicopter pilot with Leading Edge Aviation in Bend, Nicole Orlich relies on high-tech weather forecasting every day. Aviation-specific platforms provide crucial atmospheric details for safe flying: she checks HEMS (helicopter and emergency medical services) to view low-level conditions in small areas, and Foreflight, an aviation app, to get weather briefings for her planned routes.

But Orlich’s advice to others for predicting storms is simpler, requiring no fancy technology: “Go outside and look up,” she said. “Weather apps and radars are important, but they’re not enough. Pay attention to how weather systems look and feel.” In that way, Orlich has developed a necessary instinct for weather that can change midflight.

While Nicole seeks out the calmest flight path between storms, her brother also keeps watch on the skies—in search of snow. Andrew Orlich flies closer to the ground than his sister, skiing in the backcountry or at Mt. Bachelor, where he is well known for his aerial maneuvers. Growing up in Central Oregon’s rugged climate taught them both to anticipate blustery weather, even on bluebird days.

Andrew bases his ski plans on weather cues from the jet stream, pressure systems and snow accumulation.

“Winds from the north bring cold air; wind direction tells me which slopes might load with snow. Low pressure systems bring precipitation, and temperature projections tell me how to layer for the day. Then I make an educated guess about how conditions might change, so I can pivot if needed and still have an awesome experience,” said Andrew.

Few Bend locals delve into meteorology as deeply as the Orlich siblings, yet life in Bend revolves around the weather, from the tourist economy to the water supply to whether we ski on velvet or crust. Working behind the scenes are skilled experts who track the storms, interpret the data and layer science with gut instinct. These are the storm forecasters—the unsung heroes of winter.

LOCAL FORECASTING IN BEND

Many forecasters are life-long weather enthusiasts. For Katie Zuñiga, meteorology is a recently discovered passion. As a KTVZ journalist, she’s moved from producing to anchoring the news, but working with local legend Bob Shaw on weather reports was the spark that ignited her love of meteorology. “I get energized by learning the science behind the storms—how high-and low-pressure systems translate into snow and wind. I love sharing that science with others,” said Zuñiga.

“Weather reporting is unique because it’s unscripted. We never use a prompter for the forecast,” said Zuñiga. On a typical day, she studies the weather synopsis from the National Weather Service (NWS) station in Pendleton. Then she’ll compare multiple forecast models and review satellite and radar images, pulling significant elements from each layer of information. “Sometimes models don’t agree. Identifying the most likely outcome comes from deductive reasoning and experience,” said Zuñiga.

Storm forecasting in Bend holds two unique challenges, Zuñiga explained, and both are related to the geography of Central Oregon. The first challenge is a lack of radar information. The NWS operates weather radars in Portland, Medford and Pendleton. The radars send waves upward at an angle. By the time the radio waves reach Bend, they are miles overhead. “We get high-level radar information, but a lot happens between the ground and the radar image,” said Zuñiga.

The second major challenge is caused by the ground itself—that is, the changing elevation and ground angles. “Mountain regions have so many microclimates. Creating one forecast is a struggle,” said Zuñiga. Despite the variability, all KTVZ forecasts rely on data from the Redmond Airport, the nearest NWS certified weather station. “When I predict a two-inch snowfall, I know some spots will get a dusting and some way more. Precipitation and temperatures vary wildly from Warm Springs to LaPine—even across town. But we are committed to using only measurements verified by the NWS,” said Zuñiga.

PENDLETON TO BEND: THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE

Meteorologists normally fall into two camps, according to Ed Townsend. There are forecasters who interpret and communicate current weather events, and there are researchers who develop new forecasting tools and technology. As the Science and Operations Officer at NWS Pendleton, Townsend gets to do both. He keeps one foot in operations—developing and defining forecasts—and the other foot in emerging science, leveraging new research into their daily work.

Pendleton may be more than 200 miles from Bend, but information from this office forms the foundation of every local forecast. Remote tracking of winter storms is more accurate than ever, according to Townsend, thanks to the latest generation of radar and satellites. “The advancements are staggering. High-resolution satellite snapshots map the movement of atmospheric rivers like the Pineapple Express, and our upgraded radars distinguish precipitation as rain, snow, or something in between,” said Townsend. Satellite images are especially important in places like Bend, where radar coverage is weak.

The recipe for Cascade winter storms involves three ingredients: a surge of moist air, mountain topography to lift the air, and freezing temperatures to support crystal formation. Add some atmospheric instability and voila! Bendites are in for fresh snow. Predicting whether the storms show up as howling blizzards or snow-globe-style powder dumps—that is where digital analysis and human instinct intersect, said Townsend. “Ultimately, our human strengths lie in recognizing patterns and extracting the critical pieces from big data,” he added.

Do the NWS models predict a ski-friendly winter season this year? Townsend is moderately optimistic.

“There are no guarantees, but the odds are tilted toward a weak La Niña pattern,” said Townsend.

Annual snowfall in the Cascades averages over 400 inches during a La Niña cycle. A bountiful snowpack impacts more than winter recreation: it’s critical for replenishing ground water and reservoirs throughout Central Oregon. After several years of below-average snowfall, much of the Cascades’ eastern slopes are experiencing serious drought.

As Townsend explained, climate change and meteorology are related sciences, but distinctly different in their scale and timeframes. The NWS Pendleton team stays focused on their core mission: analyzing current weather events and trends from the Cascades to the Wallowas, and providing solid forecasting data to support weather-related decisions made at a local level.

WINTER EXTREMES ON A VOLCANO

Understanding winter storms at Mt. Bachelor ski resort means adding a few key terms to the weather vocabulary: tree wells, wind slabs, freezing rime and storm recovery.

“This 9000-foot volcano is the first obstacle to interrupt weather systems coming from the Pacific, so we get the full force of those winds. Combine that with our northern latitude, perfect for supercooling moist air into freezing rime, and you get gnarly, challenging mountain conditions,” said Balderach.

In addition to their own weather stations, Mt. Bachelor contracts with a private forecasting company for daily reports. They also rely on the University of Washington School of Atmospheric Sciences for models that predict snowfall intensity, and charts that graphically intersect freezing level with windspeed and direction.

Yet according to Balderach, nothing replaces real-time reports from ski patrollers with seasons of experience on the mountain. Mt. Bachelor storms follow predictable patterns. Each chairlift has a microclimate: Northwest experiences the brunt of incoming storms, with the harshest winds and rime. The intensity softens as storms wrap eastward around the mountain. Ski runs accessed by the easternmost chairlift, Cloudchaser, often feel protected on storm days…until the lift pops above the tree line, fully exposed to gale force winds. And Summit? “There are days the anemometer is frozen solid. And days it’s like skiing inside a ping pong ball, no visibility. But when we can open it, Summit is the most special place, with amazing views and ski runs in every direction,” said Balderach.

Along with the thrill of fresh powder, multi-day snowstorms bring hazards for skiers. Ski patrollers check for unsafe cornices, wind slabs that could collapse and slopes with avalanche danger. Tree wells are more difficult to mitigate. These hazards form when the lower branches of pine trees prevent snow from packing around the trunk. Skiers can easily fall into the pockets of loose snow and become stuck. Skiing with a partner and avoiding tree well areas are the best ways to stay safe.

FORECASTING FOR BACKCOUNTRY ADVENTURES

Backcountry skiers like Andrew Orlich, who forgo the ease of a chairlift, need to understand both weather and avalanche risks before they venture into backcountry terrain. The Central Oregon Avalanche Center (COAC) is dedicated to educating the backcountry community about how to stay safe.

Aaron Hartz works as a forecaster for COAC, in addition to teaching avalanche safety classes and managing his business, Hartz Science Explorations. For Hartz, the snowpack tells a story; the snow layers reveal the history of that season’s weather events. One rainy day can create an unstable layer that lasts for months. Avalanche forecasting requires awareness of the entire snow season. Building the forecasts is like solving a puzzle, fitting together weather information to create a full picture.

Central Oregon’s freeze-thaw cycles reduce avalanche danger by creating snow layers that stick together, but avalanches do happen. “Any snowstorm dropping ten inches or more is concerning, as are strong winds that push snow into huge slabs or cornices,” said Hartz.

The COAC weather station on Moon Mountain sends basic-but-important measurements to their website by modem. Any backcountry adventurer can check real-time temperature, wind speed, relative humidity and air pressure before they venture out. Hartz advises that weather analysis shouldn’t stop there.

“Keep asking yourself throughout the day if conditions are what you prepared for,” he said. “Is visibility or snowfall changing? Do I need to adjust my route or timeframe?”

WEATHER ON THE ROAD

Monitoring the weather is always partially about safety, maybe in no area more than when it comes to car travel. “We are in the business of keeping roads open. That’s why we’re here. If a road is closed, know that there is a good reason why,” said Peter Murphy, Public Information Officer for Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) in Central Oregon. Murphy is responsible for sending out emergency road alerts to first responders, news stations and county road managers.

Murphy’s team bases decisions on NWS Pendleton’s daily conference call, and stays in close contact with plow drivers and emergency responders. Because Bend is a travel destination, they monitor both sides of the Cascades, plus weather along the Columbia gorge, explained Murphy. “Certain spots on roads to and from Bend are known for a classic combo of high winds and ice buildup, like the gorge or mountain passes,” he said.

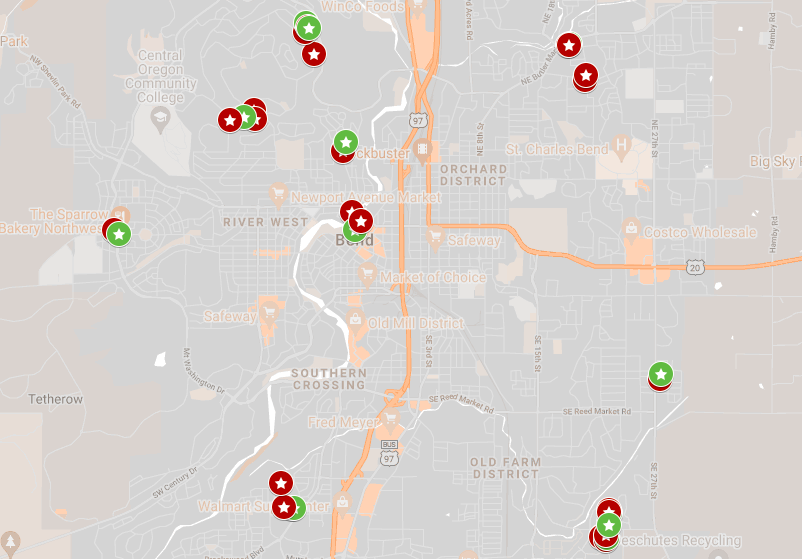

The best way to avoid winter road hazards is to use ODOT’s TripCheck.com, an online resource for road conditions and closures. Taking a moment before hitting the road lets drivers preview road conditions through live webcams and check the interactive state map for road closures and snow hazards where traction tires are needed.

This winter, when you think about the weather, perhaps you’ll think a little bit more like a scientist—or at least remember to thank a scientist for the forecast you consider. When in doubt, simply go outside and look up.

Read more about our vibrant Central Oregon community and the businesses, here.