The competing visions for the management of the upper Deschutes River, which has drawn people and sustained life for millennia, are as old as the West itself.

On the last Saturday in January, a bright, sunny affair when the promise of spring felt near, the Fly Fisher’s Place in Sisters was full of impatient anglers debating the merits of some of the shop’s 1,400 flies. But the light vibe turned serious when I asked Jeff Perin, the shop’s owner, about his connection to the Upper Deschutes River. Seated at a table in the back room of his meandering store, Perin spoke about the river wistfully, as though retelling the story of a once great athlete who had fallen upon hard times.

“I got hooked on the river the very first day we moved here, back in June 1980,” he said, his alert blue eyes shadowed by a stiff-billed fishing cap.

Perin, then in sixth grade, didn’t catch a single fish that day. In fact, he fell into the river. But his older cousin caught a slew of rainbow trout, enough to make a big impression and cement what would become a lifelong passion for the river. Perin can recall days of remarkably good fly-fishing on the Upper Deschutes as recently as three years ago, just before a devastating fish kill in October 2013 that galvanized attention to a problematic twenty-five-mile stretch of the river between the Wickiup Reservoir and Sunriver, where low streamflows have had a harmful impact on fish and wildlife.

“The river is oversubscribed for irrigation purposes,” he said. “The Upper Deschutes was once one of the best places in the country for trout fishing, but now it’s not even in the top 100.”

Most in Central Oregon agree that this stretch of the Upper Deschutes is sick, but there is no consensus on how to treat it. The conversation can be, in the words of one conservationist, a “clash of cultures” as fisherman like Perin, boaters, conservationists, state and federal agencies, municipalities, farmers and ranchers grapple for solutions and defend their turf. The debate will play out in meeting rooms and courtrooms, thanks to a lawsuit related to the Oregon spotted frog. It will continue in government offices, where officials will rule on a regulatory process initiated by eight local irrigation districts and the city of Prineville.

The competing visions for this river, which has drawn people to the region and sustained life for thousands of years, are as old as the West itself.

“There’s a reason why they say ‘whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting,’ ” said Shon Rae, communications manager for the Central Oregon Irrigation District (COID), a quasi-municipal group that has 3,623 members, mostly small farmers and ranchers.

Origins of the Last Great Problem in the Deschutes Basin

The Deschutes River runs north, covering some 250 miles, and has numerous tributaries and three sections: the Upper Deschutes, which begins at Little Lava Lake and runs down to Bend, the Middle Deschutes, which extends to Lake Billy Chinook, and the Lower Deschutes, which flows up to the Columbia River. The Deschutes is a spring-fed river that has been called the “Peculiar River” because of its remarkably consistent streamflow.

Early inhabitants of the Deschutes basin region included the Warm Springs, Wascoes, Paiutes, Klamaths, Modocs, Nez Pearce and Walla Walla tribes. Europeans began exploring Central Oregon as early as 1813. That year a pair of fur traders carved their initials and the date on a large stone on the banks of the Deschutes River, south of present day Bend.

In 1877, John Todd purchased a ranching claim along the Deschutes River he named the Farewell Bend Ranch. When travelers left the ranch and headed north, knowing it was the last bend in the river along their route, they would say, “Farewell Bend.” The nickname stuck but the post office shortened the town’s official name to Bend, since another community along the Snake River had already laid claim to the name Farewell Bend.

One of the first government reports on the water resources of Central Oregon, written by Israel Cook Russell, an early geologist and geographer, was published in 1905 and marveled about the river’s “conspicuously clear” waters.

It is a swift flowing stream … a delight to the beholder on account of its beautiful colors, refreshing coolness, and the frequently picturesque … impressive scenery of its canyon walls, as well as a blessing to the arid region to which it brings its flood of water for irrigation and other purposes. It is also an attraction to the angler and its waters are abundantly stocked with trout.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Bend evolved into a prosperous mill town along the banks of the river. The Shevlin-Hixon and Brooks-Scanlon companies opened mills on opposite sides of the river in 1916. They built a dam between them for log ponds, and the river was an indispensable conduit for transporting timber to market.

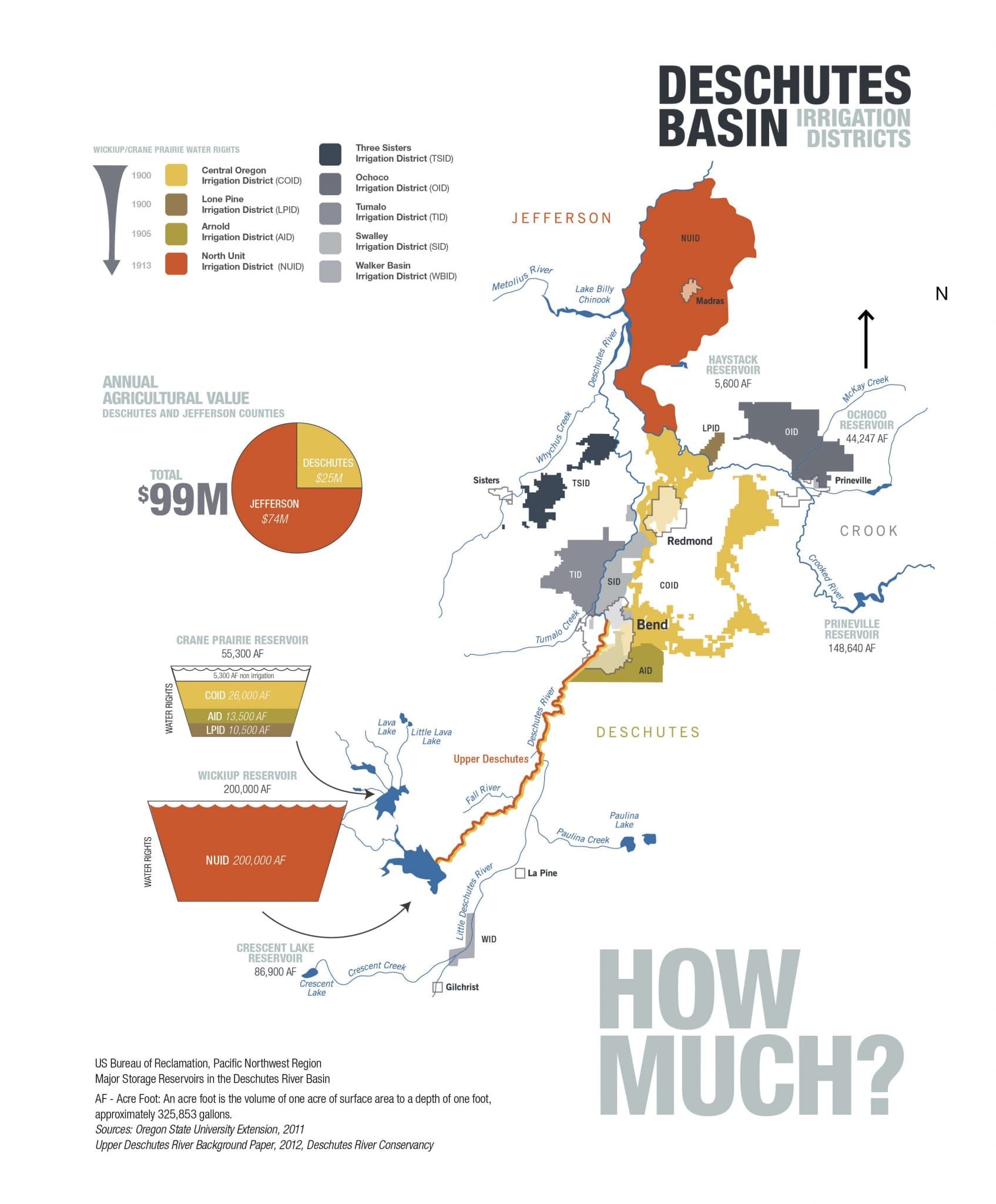

In 1894, Congress passed the Carey Act, which allowed private irrigation companies to erect irrigation systems and sell water to landowners in the arid Western states. A handful of irrigation districts were established in Central Oregon starting in 1904, and the state passed an agriculture-friendly water rights code in 1909 which encouraged farmers and ranchers to settle in the region, offering free land in exchange for the cost of irrigation. By 1924, 28,500 acres of land in Central Oregon were irrigated, supporting a population of about 10,000 people in Deschutes County.

The founding principal of the state water code was and still is—first in time, first in right—meaning the irrigation companies with the most seniority have first dibs on water rights. The eight irrigation districts in Central Oregon have “priority dates” ranging from 1899 to 1916, which dictate when and if they get their water.

A series of dams were built along the river starting in 1910, along with six reservoirs, including Crane Prairie (1940) and Wickiup (1949) on the Upper Deschutes. The Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), a government agency tasked with managing and protecting water resources, assigned irrigation districts to manage these reservoirs, which are used to store water during the winter and release it to district members during the irrigation season, April 15 through October 15.

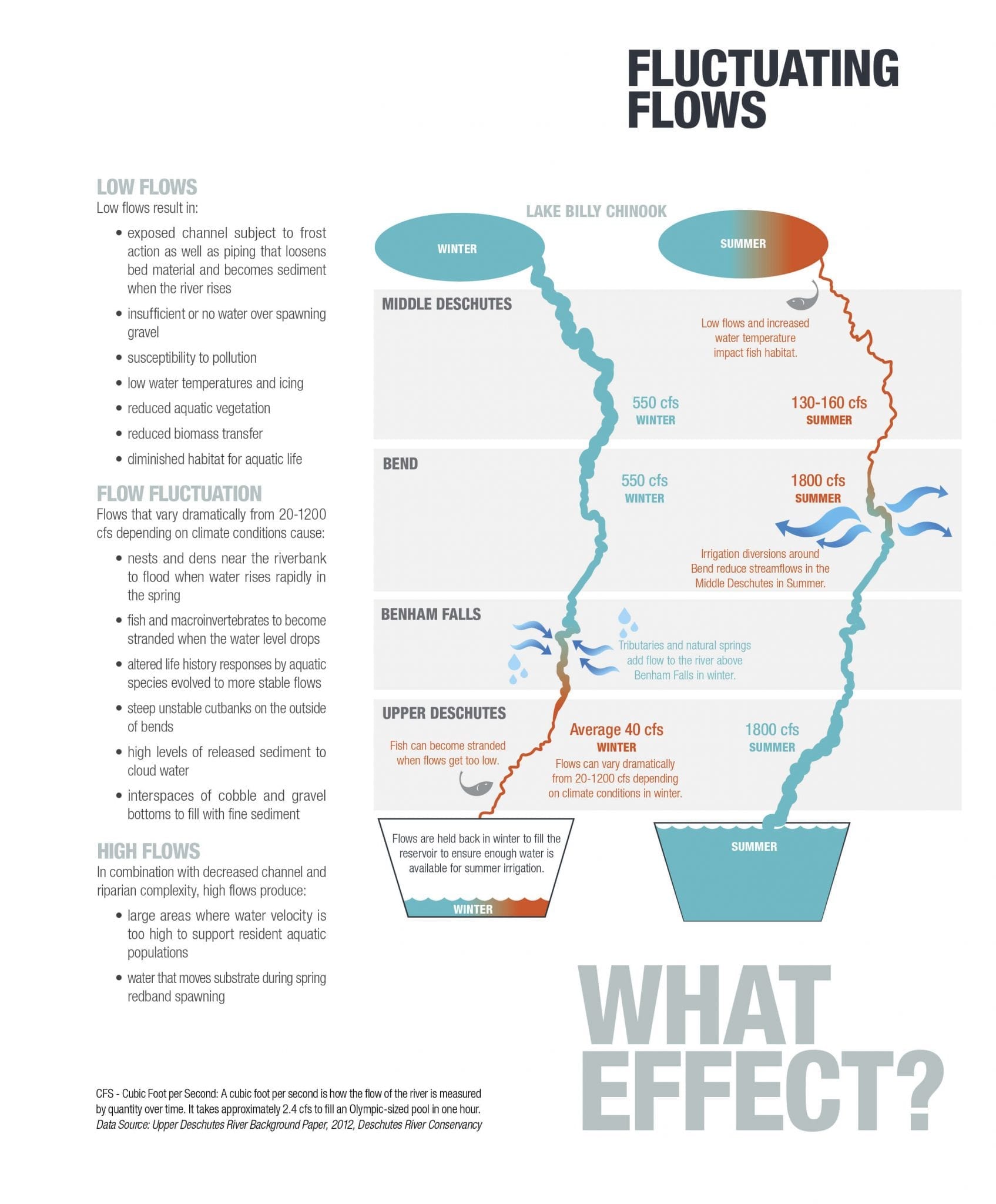

Conservationists argue that BOR and the Oregon Water Resources Department (OWRD) have allowed the irrigation districts to oversubscribe the river, hoarding water in the reservoirs in the winter and flooding the river during the summer irrigation season. The upper stretch of the Peculiar River that historically flowed at a remarkably consistent at 700 to 800 cubic feet per second (cfs) year-round, is slowed to a trickle, sometimes down to 20 cfs in the winter between Wickiup and Sunriver, and can roar to the tune of 2,000 cfs in the summer. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) has set the instream water right at 300 cfs, but that is essentially just a target—one that hasn’t been met in recent winters largely due to demand from the irrigation districts. (Climate change and a growing population in the region also play an important role.)

“It’s clear that fish and wildlife would benefit from a more natural river flow,” says Ryan Houston, executive director of the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council, a Bend-based nonprofit that takes a collaborative approach to trying to restore the Upper Deschutes. “But how do we get there? The devil is in the details.”

The Fishermen

Yancy Lind’s office is perched on a bluff above the memorable bend in the river where the Upper Deschutes morphs into the Middle Deschutes. As a financial manager who needs to follow the markets, Lind monitors four computer screens at a desk with a panoramic view of the river. But he’s also a board member of a fly-fishing group, Central Oregon Flyfishers—he’s a guy who owns no less than eighteen rods. His real passion lies beyond the screens.

“I’m obsessed with the river,” he said. Lind is intense, deadly serious when it comes to the Deschutes, and looked annoyed when I told him I was writing a story about the river.

“The river is many rivers,” he said, sweeping a hand toward the window and the view. “It has many different areas of ecological concern, and they are dramatically different. You cannot possibly write an article of any depth about the whole river.”

I conceded the point and asked him to grade the particularly problematic stretch of the Deschutes between Wickiup and Sunriver.

“If you’re going to quote me, I better be diplomatic,” he said, with a wry smile. “It’s a g**damn, f**king disaster. A complete ecological kill zone every winter. On a scale of one to ten, it’s a minus one.”

Lind is equally certain of what needs to change: the laws which grant, in his opinion, far too much latitude to the irrigation districts to manage the river. “The irrigation districts own 90 percent of the water,” he said. “And the law says that we cannot release any water instream solely for the benefit of the fish. People in Bend think we can just sit around a table and sing Kumbaya to fix this problem, but that hasn’t worked.”

When I asked about his obsession with the river, he declined to answer, insisting that my story should be about the river, not him. But when I asked again, he relented.

“People come to Bend for this ambiguous thing, quality of life, right?” he asked. “We live stressful lives. You see I’m monitoring four computer screens, and that doesn’t count my iPad and my phone. Some people do yoga, some go to church. But for me, and I think a lot of people, I go to the river. That’s what grounds me. And it’s my calling to try to make it better than it was when I moved here.”

Jeff Perin is equally passionate, but doesn’t shy away from his personal connection to the Deschutes. He holds one of just seven permits to guide anglers on the Upper Deschutes, and he was there before, during and after the October 2013 fish kill near Lava Island Falls that killed more than 3,000 fish.

“The year after that big kill, all those fish we were catching (and releasing) were gone,” he said. “If the river had been flowing at 250 cfs, it never would have happened, but at 20 cfs, those fish never had a chance.”

The Environmentalists

Paul Dewey came to Oregon in 1977, armed with a law degree from the University of Virginia, after reading a “go west young man story” in a magazine that described the state as a kind of progressive “Ecotopia.”

“I guess I was hoping it would be like a continuation of the ’60’s here,” he said.

After a stint working as a caretaker at a horse farm in Sisters, he became an attorney specializing in land use, environmental and Native American law. He founded Central Oregon Landwatch, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the environment, fish and wildlife in 1986, and has fought and won many legal battles over the years. When asked about the Upper Deschutes problem, he exhibits the energy of an idealistic college student and the passion of an evangelist.

On the afternoon I met him at Stackhouse Coffee in Bend, he was brandishing an enormous binder with materials from the Upper Deschutes Basin Study Group, a well funded, collaborative effort involving just about every water rights stakeholder in the region. I asked him if this group is likely to produce a solution to the streamflow problem.

“We’ve been studying the problem for thirty years,” he said. “Studying it is great, but we need litigation to affect change.”

The litigation he was referring to is a pair of lawsuits filed by two environmental groups, Water Watch and the Center for Biological Diversity. The latter sued the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), the former sued BOR plus the irrigation districts, alleging that their operation of the Wickiup and Crane Prairie dams is harming the habitat of the Oregon spotted frog, which is protected as a “threatened species” under the Endangered Species Act. The suits were recently combined by agreement of all parties.

Aside from what he views as antiquated water laws, Dewey pointed to “two-llamas-and-a-Prius gentleman farmers” whom he claims don’t know how to conserve water. “They use their farming losses as a tax write-off, and they don’t even grow anything,” he said. “The state considers almost anything a ‘beneficial use’ of water, so they use their water on big lawns, water features and so on.”

Ryan Houston and his group, the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council, believe in a more collaborative, less litigious approach to the problem. He says that the river has been fundamental to every stage of Bend’s evolution—from early Native American and European settlement, to its heyday as a mill town, to today’s tourism and recreation-focused economy. Houston says that we’re still wrestling with the ecological impact of Bend’s logging days—in those days, the river was cleared of much of the dead wood that rivers need to sustain a healthy ecosystem to facilitate moving logs up the river. That damage can take decades, even centuries to right, so his organization is helping to restore that habitat balance by placing dead wood back in the river. But boaters, floaters and others who recreate on the river aren’t always happy about that.

“People floating the river don’t want a huge 150-foot-tall ponderosa pine in their way as they float down the river,” says Houston, a native of Southern California who moved to Bend in 2001.

And so, the debate over how to manage the river isn’t just about streamflow, and it’s not just fishermen and conservationists versus big agriculture. Add issues such as restoring the river habitat and the interests of tourism and recreation, and you have a contentious stew indeed. Few know more about being caught in the middle of these competing interests than Tod Heisler, the executive director of The Deschutes River Conservancy, a Bend-based nonprofit that is coordinating the Upper Deschutes Basin Study, a $1.5 million collaborative process that seeks to “provide a road map to meet water needs for rivers, agriculture and communities for the next fifty years.”

Heisler says that while the problem stretch of the Upper Deschutes appears to present a “seemingly intractable” set of issues, he believes an agreement could be reached in one of three ways: through the courts, via the spotted frog lawsuit, through the voluntary basin-study group process, or through the regulatory process, based on the habitat conservation plan being prepared by the irrigation districts and the city of Prineville. (In the latter scenario, this group is seeking a permit that would essentially exempt them from lawsuits such as the spotted frog one. Their habitat conservation plan, which would need to be approved by two federal agencies, and withstand scrutiny and, potentially, lawsuits from environmental groups, would have to make the case that they have a plan to mitigate the impact of their actions on protected species such as the Oregon spotted frog.)

“This won’t be an academic report that just sits on someone’s desk,” Heisler said. “It’s going to be a solutions-based study, based on science, that could result in the negotiation of a regional water management agreeement Central Oregon so urgently needs.”

The Technocrats

If you saw Douglas DeFlitch sitting in a corner of the Bluebird Coffee Company, steeping a cup of black tea, you might guess that he works for an environmental NGO, rather than BOR. Yancy Lind only “half-facetiously” described DeFlitch, who manages BOR’s Bend Field Office, as “the enemy.” But when I met him, he had a week’s beard growth and wore a pair of faded jeans and a puffy winter coat. “Casual Friday,” he explained. And when asked about the problem area of the Upper Deschutes, he was candid, not at all like the stereotype of the secretive government bureaucrat.

“It is the last worst place on the Upper Deschutes,” he said of the stretch between Wickiup and Sunriver. “But we’ve spent a lot of money and effort working to put more water instream to solve the problem.”

DeFlitch contends that management of the river has been tilting more toward the natural end of the spectrum in recent years and will continue in that direction. But he cautions that changes cannot happen overnight because irrigators have rights that are enshrined in law, and maintains that the current system delivers large economic benefits to Central Oregon. “We’ve grown economies based upon a particular use of the river so you need to take that into consideration before you change from the way the river has been managed,” he said.

Kyle Gorman, a region manager for Oregon’s Water Resources Department, was more blunt than DeFlitch in attempting to refute claims I’d heard from conservationists. I’d heard that the existing “use it or lose it” water laws encourage waste, but Gorman says not so, because those who don’t need their water can lease it back instream and not lose their water rights. Environmentalists complained to me that the required “beneficial use” of water can include anything, even watering rocks, but Gorman scoffs at this notion, insisting that regional watermasters investigate reports of this kind of misuse. (Though he admits that there’s nothing the state can do if farmers want to have big lawns and water features.) And Gorman thinks that those who advocate for a completely natural approach to the river aren’t considering all aspects of a complicated issue.

“Folks that have the water rights, they were promised those rights and told if they developed the land and continued to use the water, they could retain those rights,” he said, “You can’t take something away from someone by just pointing a finger and saying, ‘I don’t like that, I want it changed,’ to the detriment of someone else’s investment that they’ve made.”

The Farmers and Ranchers

Matt Borlen’s ranch is situated just beyond where the rolling hills east of Bend give way to the parched farms and ranches in the tiny community of Alfalfa. Before setting foot on his property, I met some of his 300 cows—black and red Angus, Tarentaise, and Hereford, beautiful creatures who linger close to the fence and study passersby. Given the arid landscape, water rights are no trifling manner in these parts. But Borlen is an optimist, and he greeted me on a blustery morning in early February with a smile and apologies for “being so dirty.”

Borlen and his father, Bob, humanely raise cattle and provide ground beef that is used in the burgers at the Deschutes Brewery Pub and other area restaurants.

During the irrigation season, they order their water from the Central Oregon Irrigation District (COID). The water comes to them through the Central Oregon Canal, which flows behind Fred Meyer, and through the Pilot Butte Canal to a sub-canal that flows through their property. That canal leads to a pond, where a pump connects it to underground pipes that fan out across the fifty-two acres they irrigate.

“Without this water, we couldn’t grow hay, we couldn’t sustain the cows,” he said, as we tromped around the ranch against a brisk wind.

Borlen said that he’s invested tens of thousands of dollars in infrastructure improvements to make more efficient use of their water resources. He loves frogs and wildlife and “all the other things that everyone loves about living here” but is frustrated by the lawsuit.

“We all have to eat,” he said. “Food has to be produced somewhere. We want to buy local don’t we? We’re trying to be good stewards of our natural resources, but the lawsuit could shut down people like me. The money we’ll spend on lawyers could be spent on conservation, and ultimately we’ll have to pass those (legal) costs on to our customers.”

I asked Borlen about some of the “two llamas and a Prius” complaints I’d heard, and he said that his community wasn’t as tight-knit as it was years ago, so it was hard for him to evaluate how others were doing. But COID’s Shon Rae, who grew up on a farm in Redmond, said that it’s harder for small farmers to afford the kind of infrastructure that would make them more efficient. She says that COID monitors and fines “bad apples” who waste water and insists that attacks on “gentleman farmers” are unfair.

“They are getting into morals and values,” she said of the critics. “They’re saying that it’s wrong to have a small farm, they’re telling people how to live. We don’t tell them how to live.”

Seth Klann is a seventh-generation farmer whose family migrated to Oregon because of the Homestead Act of 1862, which encouraged western migration by providing settlers 160 acres of public land. He has a craft malthouse north of Madras that sells estate malt to craft brewers such as Deschutes, Ale Apothecary, Wild Ride and others. As a member of the North Unit irrigation district—which has the most recent (from 1916) and thus most junior water rights in the region—he and other farmers “at the end of the irrigation line” have had no choice but to invest in technology to be resource efficient. Klann believes that the Oregon spotted frog lawsuit could have huge implications for every farmer and rancher in the region.

“Farmers aren’t making infrastructure investments because they’re afraid they might lose their water rights,” he says. “If the water goes away, Madras will become a ghost town.”

Klann says that they get just eight inches of rain per year in Madras but need twenty to malt barley. He wants to plead his case and that of other farmers in the court of public opinion, rather than in a court of law.

“I’m frustrated because my family poured so much work into this place, moving lava rock, surviving depressions and droughts,” he said, his voice rising. “We make due with so little water and now everything—all the hard work— could be wiped away by one lawsuit.”

Solutions

On a life-affirming, perfect Saturday in January, the kind of day where the sun plants a golden kiss on the snowcapped mountains, I could hear the reassuring gurgle of Whychus Creek, a tributary of the Middle Deschutes, before I could see it. I parked at the Whychus Creek trailhead, off Forest Road 16 south of Sisters, and the sound hit me immediately. I’d come to check out the Whychus because Douglas DeFlitch and others told me it was a great example of the positive work that’s been done to restore streamflow in the Middle Deschutes region, which had the opposite streamflow problem than the Upper Deschutes (heavy streamflow in winter, low in summer). Walking upstream along the Whychus Creek trail, alongside the reassuringly regular streamflow, I could see and hear that they were right.

Four days later, at the urging of Yancy Lind and many others who had encouraged me to see the “ecological kill zone” south of Sunriver, I drove south from Bend, and parked my car on a steep, snow-covered bluff above the Deschutes at La Pine State Park. It was another gorgeous day, but the place was deserted, save for one old man with a long gray beard riding his bike with a fluffy Old English sheepdog in tow.

This time, even though I could see the river below, I recognized the problem right away: I couldn’t hear it. I crept closer and could see sections were frozen, and what was flowing was sluggish, almost stagnant. I stood close to the riverbank and had to remain perfectly still just to hear the anemic flow. Who is going to fix this mess, I wondered. Will it be a judge? A study group? A government agency? Or will it be us, the people who live here and hold this iconic river close to our hearts?

Kyle Gorman believes that we need public funding to help irrigation interests create infrastructure that will allow them to use water more efficiently. Paul Dewey and a host of other conservationists want to see water laws changed to allow for more natural management of the river. Tod Heisler and many others contend that the most durable solution will come via the collaborative, scientific study group process that includes all stakeholders.

Jeff Perin doesn’t really care how the problem is resolved, so long as he gets the Upper Deschutes of his childhood back, the river that got him hooked on fly-fishing. Perin witnessed the October 2013 fish kill, but he was also part of the grassroots “bucket brigades” efforts in the fall of 2014 and 2015 that rescued hundreds of fish. He saw how concerned citizens, anticipating that low streamflows could trap and kill fish, got together and did something about the problem, and so he knows the situation isn’t hopeless.

“When we’re quietly rowing a drift boat on a day with perfect blue skies, past all these tall trees with their red bark through these gentle currents of the Upper Deschutes, and we cast dry flies toward the banks and catch these great fish—that’s what people come back for year after year,” he said. “I still love this river and I believe we can fix it.”