photo adam mckibben

Just over a century ago, the tiny settlement of Bend was roaring into the 1920s. It was a land of adventure and opportunity, similar to current times in many ways. The population had expanded tenfold, from 536 residents in 1910 to 5,436 a decade later. Dense pine forests fueled the economy, and the Old Mill and Box Factory areas bustled with loggers and millworkers. A new dam on the Deschutes River provided the first electric power in town, creating Mirror Pond in the process. Entrepreneurs platted out new streets for homes and neighborhoods, with the bend in the river at the center.

In the midst of this boom, a few key local leaders recognized the value in preserving outdoor space for gathering and connecting with nature. Their vision led to the creation of Bend’s first parks: Drake Park along the east bank of the Deschutes River in the heart of downtown Bend, and Shevlin Park, a natural area wrapped around Tumalo Creek, on the western edge of town. In doing so they set the stage for Bend’s ongoing culture of outdoor recreation and love of nature. These parks, both established in 1921, remain the crown jewels in Bend’s park system today.

BEFORE THERE WERE PARKS

Long before European Americans reached Central Oregon, this land was important to the ancestors of the Warm Springs, Burns Paiute and Klamath tribes. Native Americans traveled seasonally along the Deschutes River and Tumalo Creek, seeking resources like berries, basket materials, medicine, fish and game. Bend is located within the lands ceded to the United States government in 1855, as part of the Treaty with the Middle Tribes of Oregon.

In 1843, explorer John Fremont passed through Central Oregon on a mapping expedition from The Dalles to Nevada. Along with guides Kit Carson and Billy Chinook, the Fremont party camped in what is now Shevlin Park. Billy Chinook eventually returned to The Dalles and became a leader of the Wasco tribe. He served as an advocate during the 1855 treaty negotiations, and Lake Billy Chinook is named in his honor. Fremont’s maps and guidebooks identified an easily crossed stretch of the Deschutes River, opening the door to settlers and loggers. By the turn of the century, Bend was on the map.

DRAKE PARK: AT THE HEART OF BEND

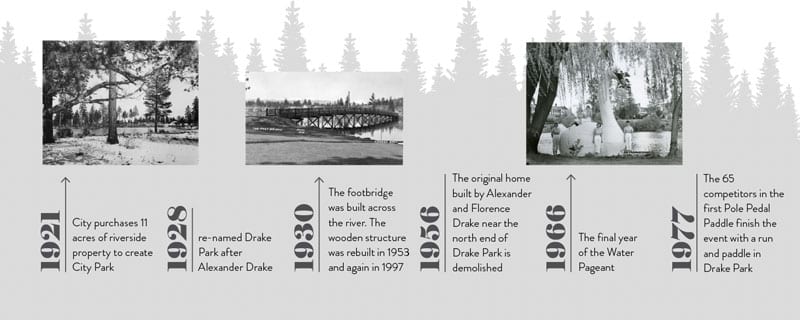

Bend’s favorite gathering space might easily have ended up a neighborhood of historic homes, if not for the Women’s Civic Improvement League and its founder, May Arnold. When the landowners drew up plans for homesites along the east bank of the Deschutes River, Arnold successfully spearheaded an effort to turn the riverside property into a city park. The women gathered 1,500 signatures from the townspeople to put a bond measure on the ballot. It passed, and the city purchased its first park for $21,000. Drake Park is named for Alexander Drake, who platted the original townsite and built Bend’s first lumber mill, irrigation canals and the hydroelectric dam that created Mirror Pond.

From the beginning, Drake Park was intended to provide a gathering place, according to Julie Brown, communications and community relations manager for the Bend Park and Recreation District. “The Women’s Civic Improvement group rallied for a town square type of park that would be at the heart of the community. Their forward-thinking vision of what this could mean for the town has had a lasting impact,” Brown said.

The first organized events established the park as the site for music and celebrations: In the summer of 1920, volunteers gathered to pull weeds, build benches and enjoy performances by the Shevlin-Hixon band. By the summer of 1921, local merchants planned Bend’s first Fourth of July celebration as a high-speed, non-stop event. As described in the Bend Bulletin on May 10, 1921, the day would start with a parade, horse races and carnival games and ended with street dancing on the new pavement, until well after midnight.

Bend’s enthusiasm for spirited celebration in Drake Park has held through the decades. The Water Pageant, an Independence Day tradition from 1933 into the 1950s, involved flotillas of lighted floats and local pageant queens atop a giant floating swan—a spectacle that brought thousands of visitors to town each year. More recently, Drake Park has served as home for the Kids’ Pole Pedal Paddle competition and the Munch & Music concert series. In between organized events, informal gatherings abound: from family picnics to slacklining teens to sports teams running drills through the park, all under the shade of the towering Ponderosa pines that were preserved a century ago.

Drake Park has grown to almost a half mile of river shoreline, stretching from the Galveston Avenue bridge to the backyard of the Pine Tavern. Mirror Pond’s reflective beauty still represents the heart of Bend, but not without controversy or negative impacts. Silt from the dam is filling up Mirror Pond, as the community debates the best solution. Crowds of people erode the riverbanks and degrade riparian habitats, keeping the Bend Park and Recreation District busy with restoring the vegetation and repairing rock walls. And about those goose droppings…feeding geese bread and popcorn is not healthy—for either the birds or the park.

Trail improvements slated for this year will improve accessibility on the trails and continue the park district’s goal of connecting pathways along the river. Brown explained, “A new boardwalk will cross the river at the north end of Drake Park, at the Newport Avenue bridge. This will connect into the Deschutes River Trail system up to Sawyer Park.”

SHEVLIN PARK: CONNECTING TO NATURE

While Drake Park is at the heart of Bend, Shevlin Park may well be at its soul. Just three miles west of Drake Park, Shevlin Park encompasses 900 acres of mixed conifers and volcanic rock outcroppings, with Tumalo Creek tumbling along the canyon floor. There’s no playground or bandstand—just trails, trees and water. “People come here to walk, find a bit of solitude, connect with nature and escape the busy-ness of town,” said Jeff Hagler, park steward manager.

Like many locals, Bend resident Sue Dougherty feels a special connection to Shevlin Park. “The first time I hiked these trails, after we moved here in 2003, it brought me to tears. I was so happy to belong to a community that would preserve a place like this, when it could have been logged off or developed,” Dougherty said. An avid birdwatcher and photographer, she tracks the changing seasons by what happens in the park. “For years I’d see a pair of mountain bluebirds in a certain snag, and I’d know spring was close,” she said. Birdwatchers can also spot Pygmy owls, woodpeckers and sapsuckers, an occasional great blue heron, and a number of migratory songbirds in the dense creekside willows and aspens.

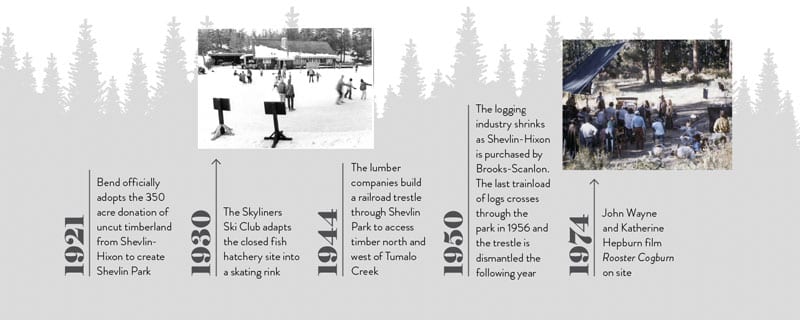

Despite its natural appearance and majestic old pines, Shevlin Park was once a working part of the timber industry. The Shevlin-Hixon Lumber company owned more than 200,000 forested acres around Bend, including Tumalo Canyon. As the logging cleared whole tracts of land around them, the company management recognized what could be lost if sections of the Cascade forests were not preserved. F. P. Hixon, Shevlin-Hixon’s president, and Tom McCann, general manager, began outlining protection for forested land around Dillon Falls and along the Dalles-California Highway (U.S. Route 97). They also designated 350 acres around Tumalo Canyon and creek to donate to the city, to be used as a park.

The park was named in honor of Thomas Shevlin, founder of the company. Shevlin was a larger-than-life Midwesterner, an athlete and entrepreneur. After building the lumber company in Bend, he traveled east to coach football at Yale, his alma mater. Shevlin contracted pneumonia and died in 1915, at age 32. The land donated in his name was donated with the stipulation that it remain a natural park for the public to enjoy, in perpetuity.

When townspeople came out to the new park, they also would visit the fish hatchery north of today’s Shevlin Road entrance. The hatchery land was added to Shevlin Park in 1929, and the Skyliner Ski Club used the pond as a skating rink for many years. Today the hatchery building is the site of Aspen Hall, and the old skating rink is home to a youth fishing pond. The pond stays stocked with rainbow trout for Bend’s kids to learn to cast and land a fish.

Shevlin Park makes it easy for people to enjoy being outside, said Hagler. “It’s such a safe place. I love that our visitors can be here without worrying, and just do their thing,” he added. Parents with strollers and kids on bikes might stick to the paved pathway; nature lovers can hike the 6-mile Loop Trail or the 2.5-mile Tumalo Creek Trail. The park also links into the Mrazek Trail for mountain biking and hiking, with a trailhead near the park entrance and a connecting trail at the south end of the park. This summer, a new trail will connect Discovery Park to Shevlin Park. The Outback Trail meanders through thirty acres of natural, undeveloped land and offers a safer, non-motorized access to Shevlin Park.

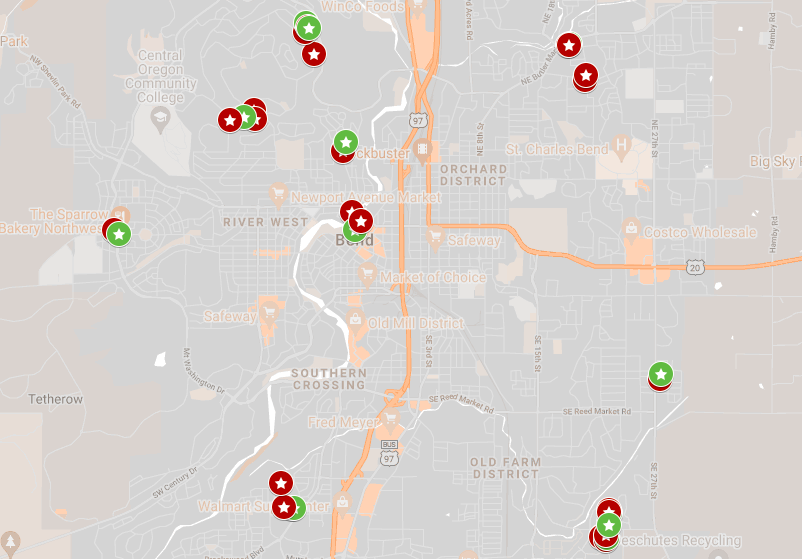

LOOKING AHEAD AT BEND PARKS

In the decades since these two founding parks got their start, Bend has added eighty more, ranging from playgrounds to off-leash dog parks to community gardens—with more than seventy miles of trails. This year, the park district broke ground on its eighty-third park: the Alpenglow Community Park in SE Bend. Alpenglow Park will include a “sprayground” water feature, event pavilion and grassy lawn, an off-leash dog play area and multi-use trails. The park is expected to open in 2022.