In 2014, the federal government spent more than $1.5 billion on wildfire suppression in the United States with two of the largest wildfires happening here in the Pacific Northwest. The Carleton Complex Fire, the largest Washington has ever seen, burned 256,000 acres in the Methow Valley over two weeks in July. At nearly the same time, the Chelaslie River fire in British Columbia took out 330,000 acres.

Putting out wildfires takes expensive equipment and high wages to pay high-risk firefighters. Further, the frequency and the size of wildfires are oblivious to budget constraints. In Central Oregon, surrounded by national forests, the federal government owns about 55 percent of all land and the vast majority of forestland in Central Oregon. Being on the dry side of the state and surrounded by trees, Central Oregon has made up most of the state’s overall wildfire suppression expenses in the past. However, with increasing temperatures throughout the state, many areas like Grants Pass, Douglas and Klamath Falls are seeing more wildfires than ever before.

This past summer was a standout fire season with costs reaching higher than normal, according to Central Oregon assistant district forester Tracy Wrolson. The Waterman Complex fire, near Mitchell, burned through more than 12,500 acres over two weeks, involved 373 personnel that included nine crews, fifteen fire engines, four bulldozers and one helicopter. This fire alone cost $6.5 million and accounted for nearly a third of Oregon’s total firefighting cost of $22.5 million. The year 2014 was Central Oregon’s second-most expensive year for wildfires within the last fifteen years, close behind 2013.

An August report by the U.S. Forest Service warns that climate change is forcing the agency into uncomfortable areas. “The U.S. burns twice as many acres as three decades ago and Forest Service scientists believe the acreage burned may double again by mid-century.”

More acreage is burning, but an entirely new problem skyrockets costs even further: the wildland-urban interface. In the 1990s, Central Oregon and many similar areas around the country saw a construction boom with houses being built in or near forests at high risk for wildfire. “Fighting a wildfire in the wildland-urban interface is much more complex than in a pure forest setting,” said Rod Nichols, public information officer for the Oregon Department of Forestry. “This requires more fire suppression resources, which runs up the cost considerably.”

The History of Oregon Firefighting

Twenty years ago, fire suppression accounted for 16 percent of the Forest Service’s annual appropriated budget. This year, for the first time, more than 50 percent of the Forest Service’s annual budget will be dedicated to wildfire,” the U.S. Forest Service report noted. Last year, the Forest Service’s ten largest fires cost more than $320 million dollars. The cost of fire suppression is predicted to increase to nearly $1.8 billion by 2025.

In a cost breakdown of any given fire, aircraft and firefighters are the most costly. An air tanker costs more than $14,000 per hour. The largest helicopters come in at around $150,000 per day. A single firefighter’s wage averages forty dollars an hour, often working twelve to fifteen-hour days, and working in crews of twenty. A department can spend $1.3 million on manpower in just a week. Other costs include catering, fire engines and water tenders, and personnel who manage crews of firefighters.

The general cost of fighting wildfires is on an upward trend, but the Oregon Department of Forestry says it’s doing everything it can to reign in cost on its side.

“This agency has historically been very frugal,” said Rick Gibson, former fire prevention manager at the Oregon Department of Forestry. “We’re always looking for new opportunities to keep costs down.” The department’s strategy is to swarm a fire quickly as possible with as many resources as feasible. While this may cost more on the front end, it has proven to decrease costs in the long run. “Keeping it small” is the goal around here, according to Gibson.

Modern Advancements

From watchtowers staffed with people with binoculars to today’s thermal detecting drones, fighting wildfires has evolved into a deeply researched, complex technological operation.

Thousands of innovations have been developed over the past century with the intent of making wildfire fighting more safe and predictable and fires more preventable. Wildfire fighting is quickly becoming high-tech up and down the West Coast.

The discussion around new firefighting technologies is overwhelmingly dominated by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), more commonly referred to as drones. The Southwest Oregon District of the Department of Forestry, in Central Point near Medford, has two UAVs and a trained pilot to fly them, with plans to deploy them this summer. “As far as a fire department owning its own unmanned aircraft, I believe we are one of the first in the nation,” said Matt Krunglevich, prevention planner for the southwest Oregon district.

Drones offer a few advantages to wildfire fighting agencies — they’re more cost-effective, timely, and, in some cases, safer. Putting a person in a helicopter to survey an area of a forest can run up to $3,000 an hour, while buying one aircraft can be a one-time purchase of $5,000. Further, drones could potentially provide live and continuous data through the use of cameras so that firefighters wouldn’t have to rely on data that was collected several hours ago. And, as opposed to a manned helicopter, if a UAV crashes, there are no people in it, said Krunglevich.

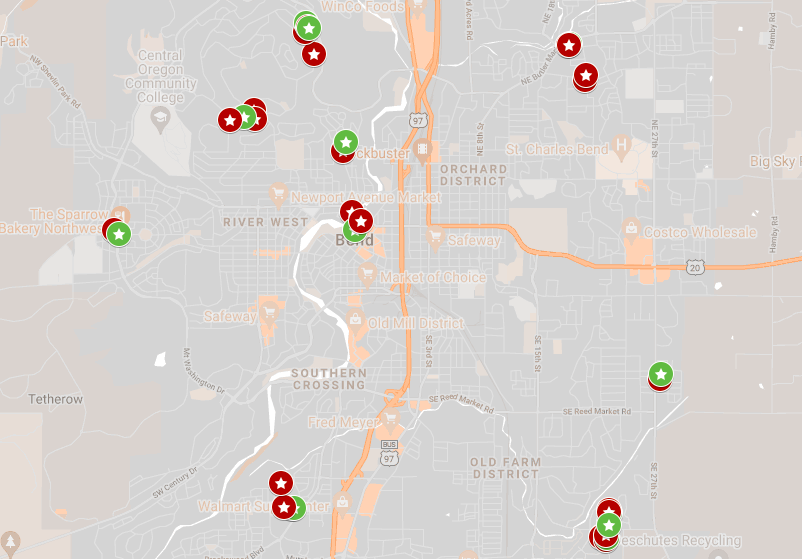

One tech company, FireWhat, Inc. is using Geographic Information System (GIS) technology to help wildfire fighters respond faster and more efficiently to emergencies. Recently merging with Geo-Spatial Solutions and opening an office in Bend, FireWhat has revolutionized wildfire response with its highly interactive, wireless mapping. The company designs custom programs for individual fire agencies, but it also has a public website, WildlandFire.com, where anyone can find details of wildfires in their area. According to CEO Sam Lanier, FireWhat is also testing drones as another tool in data collecting, partnering with Aerovel based in White Salmon, Washington.

Douglas County is paving the way for different kinds of technology that are quickly spreading to other parts of Oregon. The ForestWatch fire detection system is a series of cameras strategically placed in high-risk areas, detecting the earliest signs of smoke. A control center receives these alerts and the exact coordinates of the threat, enabling a speedy dispatch for a response. Developed by EnviroVision Solutions in Roseburg, the detection system has made its way to The Dalles and will be installed in the John Day area within the next year.

In the Oregonian tradition of “going green,” Central Oregon will use an environmentally safe retardant called FireIce for the first time this year. This fire retardant gel replaces the commonly used chemical foam that can be toxic to wildlife when used in large amounts. “Normally, you have to be careful where you drop fire retardant,” said Tracy Wrolson, assistant district forester of Central Oregon. “This [new retardant] does the same job and can be used in sensitive areas.”

Though more technologies are being developed to help make quicker, better decisions about wildfires, the man-powered physical nature of firefighting remains. “The reality is that the way of putting out a fire is the same,” said Dennis Lee, protection unit forester of the Klamath-Lake District. “We still have some of the same tools from 1908.”