There’s a crispness to the air. Every breath produces a wisp of steam. The upbeat music, piped in from overhead speakers, encourages spectators to join the fun. It’s Open Skate at The Pavilion, where skaters of all ages and abilities gather in Bend.

The natural wonders of Central Oregon have inspired enthusiasts since the establishment of the city in the early 1900s. Ranchers sought outdoor entertainment on sunny winter days, and Scandinavian mill workers imported their reliance on what they referred to as friluftsliv—outdoor living—to cure the challenges of those first days.

The abundance of lakes around Bend helped bring ice skating to the region. Local skating enthusiasts favored the upper part of the failed Tumalo Reservoir and the abandoned fish hatchery pond at Shevlin Park. The only requisite was a little help from Mother Nature to bring a freeze to standing water. It would take until the founding of Bend’s first ski club in 1927, Skyliners, before organized skating became a popular winter sport in Central Oregon. Helping the rinks take form was the job of ice makers, and the first was Myron Symons.

Bend’s First Ice Maker

Born in Stafford, New York, Symons came to Bend in 1915 from Dawson, Yukon. He hit it off with Skyliners’ founders, Chris Kostol, Emil Nordeen, Nels Skjersaa and Nils Wulfsberg, and quickly became involved in the skating community. The Bend Bulletin called him, “one of Bend’s most enthusiastic exponents of the winter sport.”

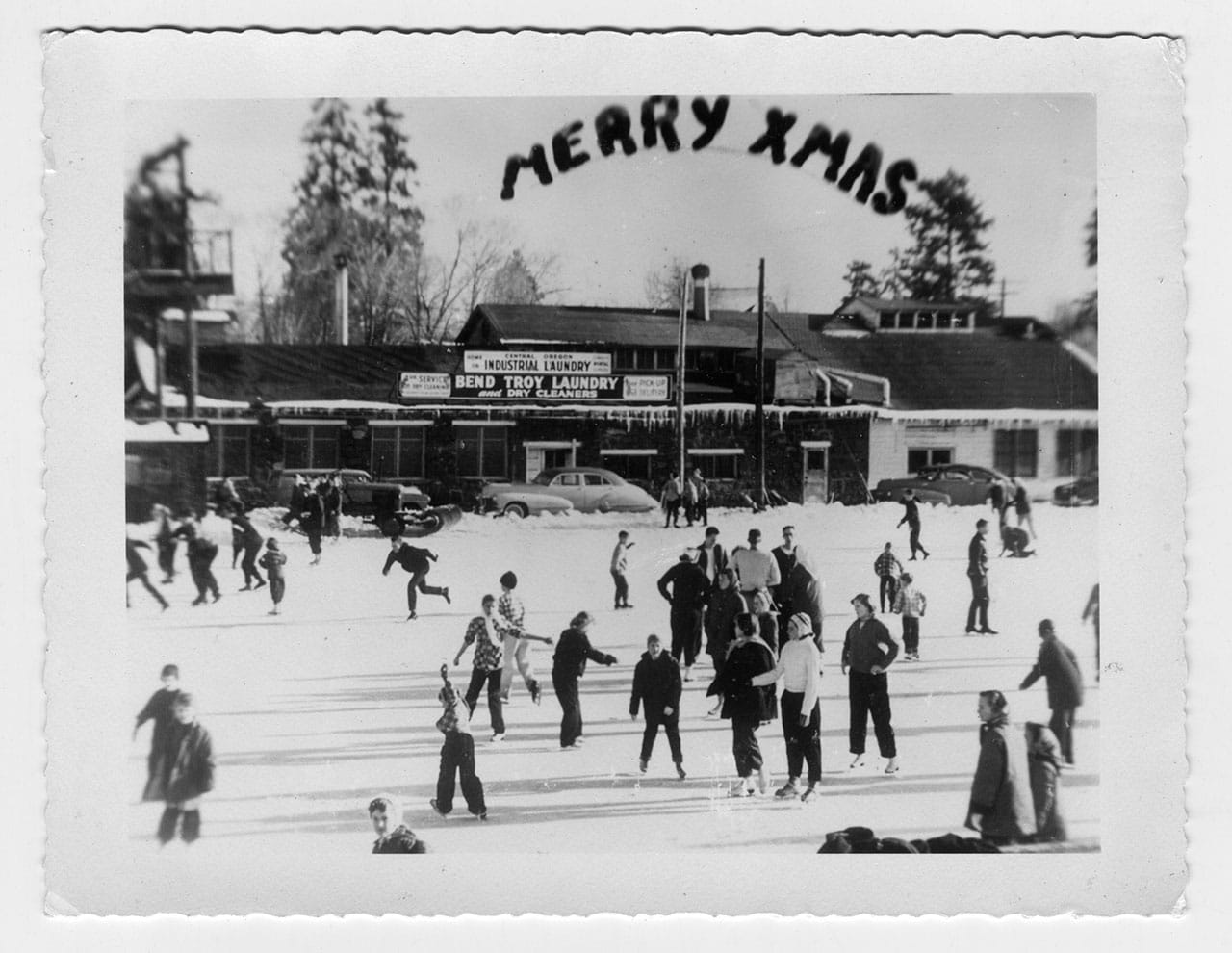

He began making ice for Skyliners in the 1930s and was instrumental in the creation of an outdoor skating rink at Skyliners’ winter playground located near the upper Tumalo Creek in 1938—where Skyliner Lodge can still be found. The technique he used was the same throughout his career: He flooded the area, building up a 3-inch-thick slab of ice. After the ice was set, he sprinkled hot water to fine-tune problem areas. With Symons’ help, Bend’s first skating rink came to fruition in 1949 at Troy Field, the open area nestled between the original Bend High School (today Bend-La Pine’s administration building) and St. Francis School (now known as McMenamins Old St. Francis School). Symons relied on the Bend Fire Department to flood the field with fire hoses. “The tap to access the water was made from a fire hydrant at the northwest corner of the field,” said Jim Crowell, who used to skate at Symons’ rink during his grade school years. Symons used any excuse to be on the ice himself. Crowell recalled Symons as “the guy who glided around Troy Field, an elder statesman of inner-city skating.”

Ice Master Today

Today, Donne Fox Horne is the maestro of ice as Zamboni operator at Bend Parks & Recreation’s The Pavilion. Growing up in Woodstock, New Hampshire, Horne has skated since his early years. “If the ice on the pond was thick enough, we didn’t go to school that day,” Horne said. After spending 25 years maintaining the ice arena at the Holderness School in Plymouth, New Hampshire, a visit to Bend in 2015 changed Horne’s trajectory. That same year, The Pavilion opened, with its NHL-regulation size rink of 200-by-85 feet of ice. Horne found a home at the new rink, a place to create ice magic with the help of a Zamboni.

From Flooding to Zamboni

Unlike Symons’ flooding technique, Horne relies on the 11,000-pound Zamboni machine to maintain ice at The Pavilion. “I usually get here at 4:30 in the morning to start resurfacing the ice,” said Horne. The technical wizardry happens at the tail end of the Zamboni where an apparatus that touches the ice contains everything needed for producing perfect ice—one-sixteenth of an inch at a time.

First, a knife shaves the ice while an auger removes the slush. Next, wash water is sprinkled onto the ice followed by a vacuum, which removes the dirty water. The final phase is a sprinkler system that sprays hot water onto the ice, followed by a towel that spreads water evenly behind the Zamboni.

Horne also has a secret weapon to battle warming trends, something that wasn’t available to Symons. The cement slab below the ice acts as a giant freezer. “We have between nine-11 miles of pipes that move a 19-degree glycol mix underneath the slab,” said Horne. “Think of it like the back of a refrigerator.”

Bend has come far from its early days of frozen ponds, irrigation ditches and the flooded Troy Field. From late October until early April, the ice at The Pavilion provides a centerpiece for winter sports. Myron Symons would be proud. See bendparksandrec.org.

Read more about our vibrant community and Central Oregon heritage articles.