When the Awbrey Hall fire blazed through a 6-mile corridor west of Bend in 1990, it laid bare a swath of land that would eventually become Shevlin Commons: a high-end neighborhood with some of the city’s most visionary building guidelines and award-winning architecture.

In the late 1990s, a developer with property bordering Shevlin Park proposed construction of 164 homes but abandoned the plan due to intense community opposition centered on the value of Shevlin Park.

In 2001, the property owners agreed to sell seventy-six acres to Bend resident and attorney, Andrew Crosby, who worked to achieve consensus among disparate perspectives for developing a portion of the property into housing while respecting the landscape. “The conservation community was concerned about the possibility of having multistory townhouses along the park boundary,” Crosby said. “People stepped forward because they cared about the property and wanted to preserve the feeling and keep open space.”

The center concept was a forty-three-acre conservation easement granted to the Bend Park & Recreation District that became a permanent, protective overlay and interface with the neighborhood.

The remaining thirty-three acres would provide lots for sixty-six homes and open-space communal areas. “I didn’t want large, poorly conceived homes packing the landscape. On expensive land, there’s always a pull to go bigger, and that was something we were trying to avoid,” Crosby said. “We capped height and square footage in three different zones.”

Lots ranged from 5,600 square feet to a half-acre in size. Homes closest to the park would be limited to a single story, with the second zone capped at one-and-a-half stories and the third zone at two stories. Construction guidelines promoted at-grade living to create a feeling of homes “being rooted in the landscape,” he said. In addition, design guidelines also promoted green and sustainable housing.

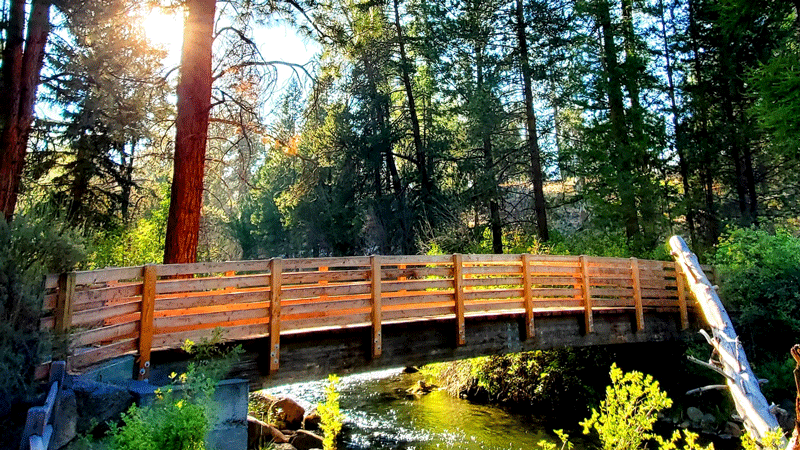

“Andy and his team created design guidelines true to the original idea,” said Susan Castillo, a resident since 2009 who served on the Shevlin Commons design review committee until recently. She and her husband hired James Cutler, the Seattle architect who designed Bill Gates’ 66,000 square-foot home, to design their home in the Overlook Pavilion zone closest to the park. “The neighborhood feels open yet close to town; rural but not remote,” she said. “We can go out the door, walk the dog down to the creek—which we can hear from our house—and see great horned owls on the snag nearby.”

Both Castillo and Eileen Drake, board president of the Shevlin Commons Community Association, agree that most people understand and support the design guidelines. “For some of us, [the design guidelines] are absolutely working,” Drake said. “We can’t find any place else like it.”

However, two decades into the development, they say new owners don’t always understand the purpose of the neighborhood and can struggle with the restrictive guidelines. For example, the design guidelines don’t allow non-natural siding, and homeowners can’t build fences or plant lawns and vegetable gardens. Landscaping is limited to native plants inventoried at the site or Shevlin Park. The result is open space around each home with pathways for residents and wildlife to crisscross the neighborhood.

“It’s not for everyone if they don’t embrace the nuances of living in nature and preserving the night sky,” said Drake, who along with her husband, built a home in the Forest Lodge, two-story zone in 2015. “We have lots of positive choices, including the option to interact with nature. This neighborhood takes that connection to a degree not found in any other area.”

Most people knowledgeable about Shevlin Commons agree that strict adherence to the design guidelines and the conservancy overlay makes it unique and highly desirable among high-end developments in Central Oregon. Drake reports that home sales are rare and happen quickly, often within a couple of days or weeks.

Of the sixty-six original lots, fifty-three have homes on them. Seven of the thirteen remaining lots are in a phase of construction, and the six other lots are not currently for sale—including those owned by adjacent property owners to protect their privacy. Home sales in the past year ranged from $2.2 million to $3.2 million.

Because homes weren’t intended to be large, Crosby built Bearwallows Pavillion, a community center with a large, grassy field to create space for casual gatherings among residents and their guests. The center won awards for its architecture and was a model of green construction, he said. Unlike other nearby developments like Tetherow or Broken Top, Shevlin Commons doesn’t offer resort amenities attractive to certain buyers.

“Shevlin Commons has been successful,” Crosby said. “It appeals to a certain buyer with a conservation mindset.”