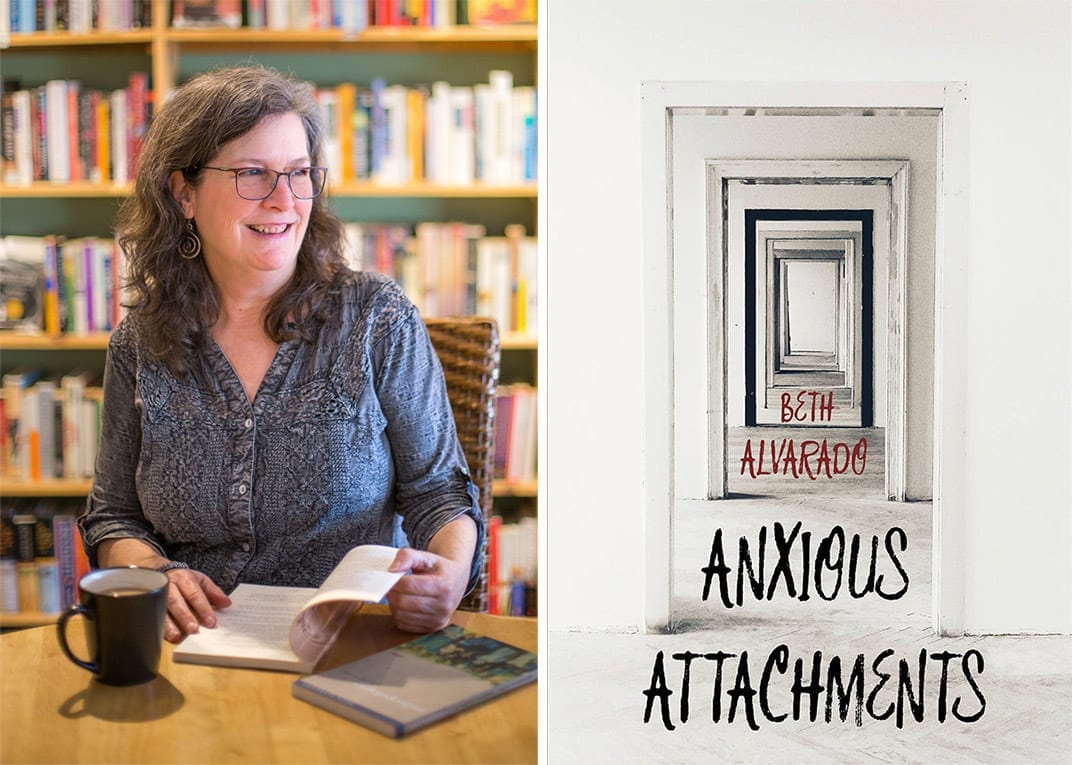

Local writer and OSU-Cascades faculty member Beth Alvarado talks about family, anxiety and more in her latest collection of essays, Anxious Attachments.

Beth Alvarado comes from a family of storytellers, so it’s no surprise that she found writing as her creative outlet and ultimately her career. In 2013, after her husband died, she started spending summers in Bend and moved here in 2016 to be closer to her daughter and grandchildren. She is core faculty at OSU-Cascades Low Residency MFA Program, where she teaches prose, both fiction and creative nonfiction. Her third book, Anxious Attachments, is a book of essays that will be published in March from Autumn House Press.

Tell us about your new book.

This is my third book; these essays span events that took place over forty years of my life. Many of them are about personal struggles—quitting heroin, caring for preemies, tending to the dying—but none are purely personal. Instead, each takes up issues that have affected my family and cause me a lot of anxiety, especially when I think of my children and grandchildren. Although the theme of anxiety runs through the book, I have also woven my story with my husband, Fernando, through it. Even though he died, he is still the glue that holds everything together for me. I think being married to him gave me a way of seeing our individual lives as being part of a larger web of lives—how everyone is connected and how we are, therefore, responsible to one another.

What topics do you cover in your essays?

One essay is about Fernando’s cancer in the context of the water pollution in Tucson that contributed to his death and to the deaths of approximately 20,000 other people, primarily Mexican and Native Americans; one is about caring for my infant grandchildren in Bend last summer, while surrounded by wildfires; another essay explores the ramifications of school shootings and video games in my life as a teacher and in the lives of my older grandchildren who attend public schools; another is about a journey I took to Mexico to see the place where my father-in-law was orphaned during the Mexican Revolution.

When did you first realize you were a writer?

I was a kid who went to the library every weekend and checked out a stack of books. I always wanted to write. My mother wanted to encourage me, so she refurbished an old Underwood typewriter and gave it to me along with a copy of Writers’ Digest Magazine. I had always wanted to draw but had no talent for it, but I could describe things in words. Later, in high school, I loved black and white photography, but it was too costly to pursue. When I got married, I started writing again. It was as if I needed some kind of creative outlet, and I always had paper and pens. In some ways, because I got married and had children so young, I think writing became this place in my life that was just for me, where I could be myself and remember who I was as an individual.

How did you carve out time for your writing while you were a busy mom with young children?

It wasn’t easy. I think the hardest thing is having any solitude for thinking. Like William Stafford said once, writing is like fishing. You have to cast the line out every morning and see what happens, but with young children, of course, you don’t have that luxury. Back when my kids were little, I had to stay up really late at night to write or study. And if you’re writing, teaching, and caring for others—each of those activities requires focus and attention. They are not things you can put on automatic pilot. And so you need to tell yourself to give over specific time to your writing, even if it’s only two mornings a week, and then you need to protect that time.

What do you recommend to people who are interested in writing themselves?

Initially, I wanted to be a poet, and the advice that I was given was, “If you want to write good poetry, read contemporary fiction.” So I did. I read everything in this anthology my husband had from his English class at the community college. Katherine Anne Porter and James Baldwin were two of the writers I liked and so I went to the library and got all of their other books. By the time I did go back to school as an undergraduate, I had already educated myself—but I had given myself an alternative education because when I was in school in the ’80s, you could go for whole semesters without reading one woman writer or one writer of color and those were the writers who spoke to me and whose work affirmed my own attempts at writing, my own subject matter. That’s kind of a long way of saying: be a reader if you want to be a writer. I have heard so many writers say that their best teachers were books.

Why was finding a creative community in Bend vital to you?

I told myself I would never be one of those people who retire and then follow their children. I never wanted my daughter’s life to become my life, and she didn’t want me to do that either. But living near her, and closer to my son and his family in Boise, is every bit as important as my writing life in Tucson. It goes back to that central conflict, the pull between family and the writing, and it’s partly why I made the move gradually and why I wanted to be involved in OSU – Cascades. I had to meet other writers. I had to find my creative home. Now that I’ve been here for a few years and met other writers and now that my most recent writing is set here in the Oregon high desert, I am starting to feel as if I’ve found a new home.