Trophy trout are just part of the appeal at Southern Oregon’s Lonesome Duck ranch.

You’re not likely to just stumble across the Lonesome Duck Ranch. The rustic, yet cozy, getaway is tucked into a strip of private land just east of Highway 97, near the old logging town of Chiloquin. The property, which owners Steve and Debbie Hilbert acquired some twenty years ago, sits on the east bank of the Williamson River about a mile upstream from where the river passes beneath the highway. A small sign bearing the ranch’s logo is the only prompt to turn left at a small opening in the guard rail, just south of the Kla-Mo-Ya Casino, and onto a private road that serves as the only way in and out of the riverside resort and adjoining ranch.

The Hilberts sold off the ranch portion of the property several years ago, as well as a custom home they built and operated as a bed-and-breakfast for almost two decades. Hilbert said they made the decision after realizing that their semi-retirement retreat had left them “land rich, but cash poor,” not to mention constantly overworked.

The Hilberts found a willing buyer and now lease back the barn and pasture from the new owner, who is more interested in fishing than ranching (more on the fishing in a bit). Not ready to leave their river sanctuary, Steve and Debbie downsized in 2013, moving into a smaller guest house that they remodeled as a permanent home by adding and upgrading appliances. The shuffle left them with two rental cabins and no bed-and-breakfast to tie them down.

Despite the scaling back of the operations at Lonesome Duck, the essential draw of the river endures. I made my first and only visit on a mid-summer weekday evening, one of the only times that Hilbert could find a small window of vacancy at the property, which serves as a basecamp for anglers in pursuit of trophy rainbow trout. It’s also a launching point for a visit to Oregon’s only national park, Crater Lake, which is located about fifty miles northwest of the property. With few other lodging options closer to the park, the Lonesome Duck has an international appeal. Flipping through the guest ledger in our cabin we saw notes from previous visitors who come from as far away as London and Germany.

Our travel plans were less ambitious. After confirming a vacancy a few days prior to the date, we packed up on the afternoon of our visit. Throwing a few extra clothes and a few snacks together (there is no on-site restaurant or provisions), I hopped into the truck with my somewhat reluctant daughters whom I had enlisted for company.

Hilbert greeted us upon arrival, motoring over from his nearby residence on a side-by-side four-wheeler, his enthusiastic black lab, Clara, sitting beside him on the passenger seat. (Like other elements of the ranch, Clara takes her name from a character in Larry McMurtry’s classic Western novel, Lonesome Dove.)

Hilbert, a University of Oregon graduate, said he first learned about the Williamson from an article in a fly-fishing magazine. After spending most of their professional lives building an interior design business in Lake Tahoe, Hilbert and his wife were ready for a change of pace. They found the Lonesome Duck property in the mid 1990s and spent the next several years shuttling back and forth between Lake Tahoe and Chiloquin. They made slow but steady progress, refurbishing an old railroad cabin that served as the main farmhouse residence. They removed junk cars and piles of trash and restored the home room by room. In 2005, They designed and built a 4,000-square-foot home that served as a two-bedroom bed and breakfast and their primary residence.

Rustic relaxation is the primary theme at Lonesome Duck, where days pass by as lazily as the river out the front door. Hilbert provides kayaks and canoes for guests, who can fish or just slip quietly downstream, while osprey and eagles perched in towering ponderosa pines adjacent to the river watch from above.

Before playtime could begin, we settled into our accommodations, a two-bedroom cottage with a comfy living area, surprisingly large kitchen and full bath with claw-foot tub. In the main living room area, a stone hearth occupies a wall above the fireplace. Hilbert points to native arrowheads embedded in the stones and explains that Lonesome Duck Ranch was once a native fishing grounds and village.

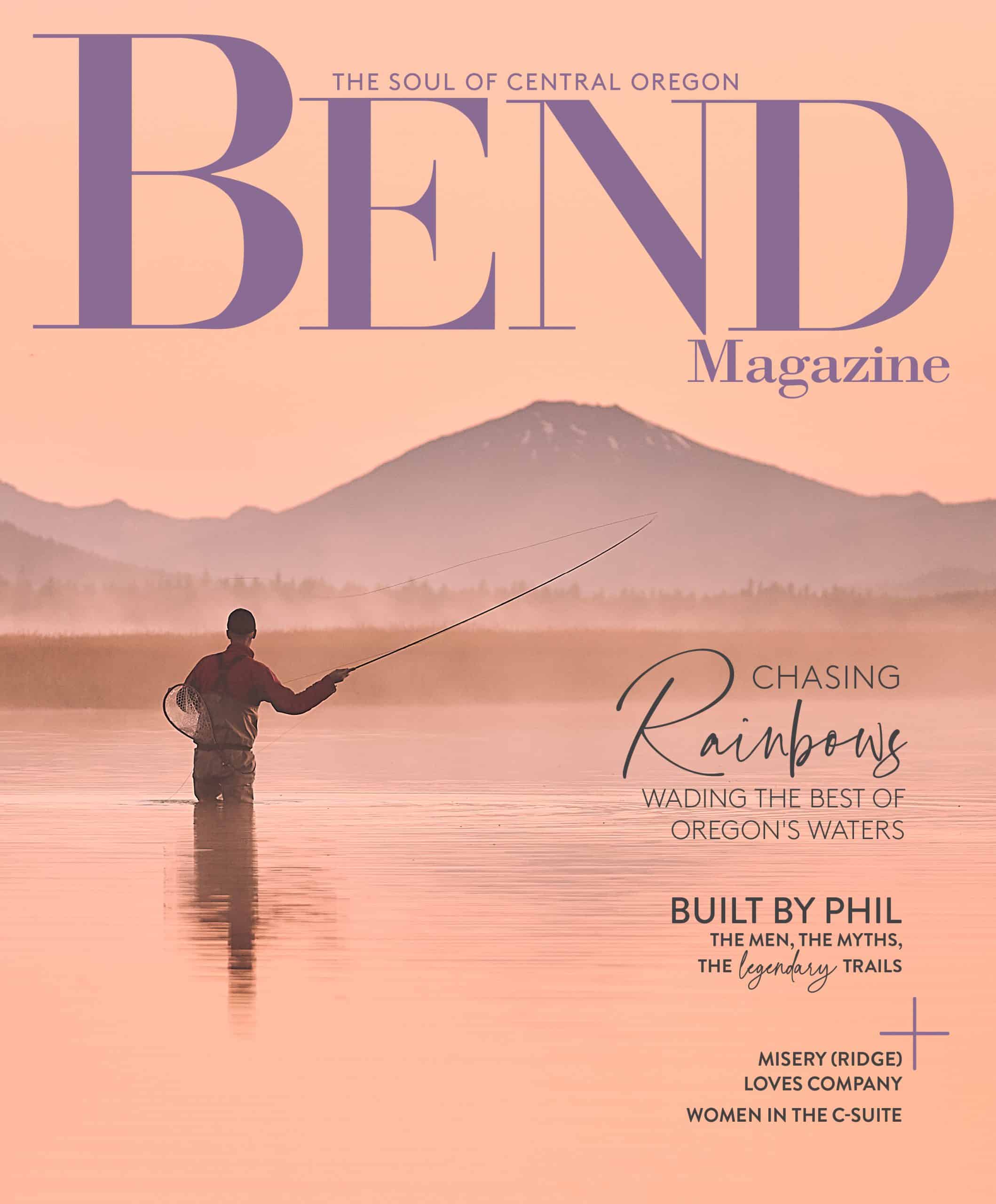

That was our cue to hop in Hilbert’s ClackaCraft drift boat that he keeps handy for opportunistic excursions. I’m not much for guided trips, but in this case I’m happy to have Hilbert’s help. The Williamson is a riddle. A languid creek with almost no discernible current.

Hilbert oars gently downstream toward a downed log. Before reaching it, he drops anchor. He advises me to peel off as much line as I’m comfortable casting. Maybe more. I do as I’m told and drop a marginal cast at forty-five degrees downstream. “Mend,” Hilbert directs, asking me to ease tension on the line by tossing loops of slack line upstream. I toss the mend. “Again,” Hilbert says. I toss another mend. “Another,” he says. “Now wait.” After a solid six seconds, he tells me to begin retrieving the fly. I begin pulling in line with long strips. Hilbert stops me. “Small strips—one inch,” he says. I try again. Still too aggressive, he says. I start to get the picture. I’m not so much stripping in line as teasing it in.

As we work the water downstream, we repeat the same sequence. Long cast. Mend. Mend. Mend. Wait. Tiny fingertip strips.

Nothing.

After almost two hours, dusk is closing in. We motor back upstream, and Hilbert drops me in front of our cabin. He leaves me the boat in case I want to give it another shot in the morning. As twilight envelops the ranch, I drop into an Adirondack chair on the porch with a cold beer while the girls play cards inside by lamplight. We drop steaks on the grill with fresh corn and enjoy a family meal as night settles over the ranch. After dinner, we shake Yahtzee dice as yawns set in. I set my alarm for 6:30 a.m. We need to be out of the cabin by 10 a.m. for the cleaning crew to prepare it for the next guests.

Dawn arrives early with a chill. I grab an extra layer and my fly rod, then head to the river. I decide to go upstream to a riffle that provides some structure and a semblance of familiarity to my eye. After a tug on the line on my second cast, I spend a fruitless hour casting and stripping to no avail. The sun works its way across the water and fish begin to rise around me. Time is slipping away, and my best chance to catch one of the legendary trout is already behind me. I pick up anchor and row downstream to where Hilbert and the girls are walking a pair of llamas. I work toward the edge of the pasture and a fence post where Hilbert spotted several fish a few days ago. Hilbert sees me and wanders over. He takes up a position and within a few seconds his trained eyes spot a fish. Then a second. And another.

“Move the boat a little close, maybe five feet,” he instructs.

I move the boat and drop both stern and bow anchors to hold my angle in the current for an optimal presentation. My first cast drops well short. I make another. Better, but too far downstream. I make a third cast. “Let it sink,” Hilbert admonishes, reading my nervous thoughts. I begin the small strip tease. One, two, three….

“Bang!”

An unmistakable grab of a large fish. I lift my rod. Nothing. Hilbert sees it all.

“Fish?”

“Yes, nice one.”

I keep stripping. One, two, three, four.

Fish On!

The rod doubles over and Hilbert allows a smile. After several leader-straining runs, the fish comes to the net. It’s at least 18 inches long. A migratory fish that bears signs of its recent lake residence. I hoist it into the boat and the small hook pops free. A tenuous connection.

It’s 10 a.m. Time to go. But I can’t resist, just one more cast. Maybe two. I know Hilbert understands.