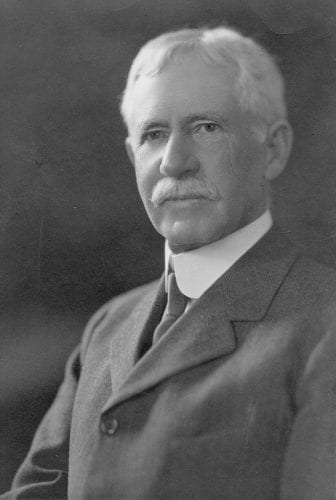

Take a look around the heart of Bend, and it’s hard to miss Alexander Drake’s handiwork. Drake arrived in Bend more than 100 years ago, but his fingerprints are all over this town, even if you don’t know where to look.

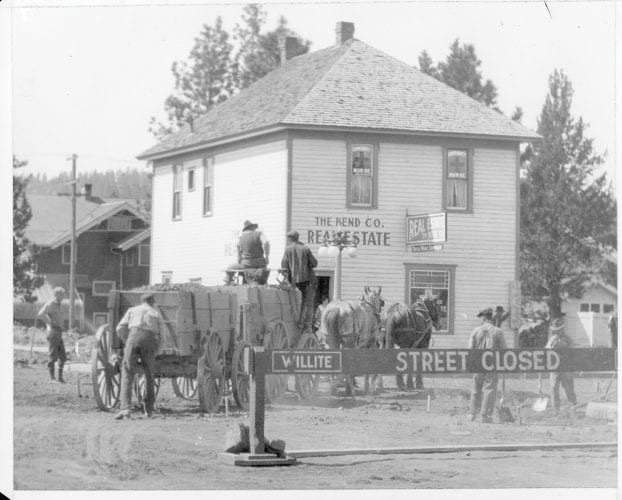

Drake laid out the town’s street grid, opened the first sawmill, developed the first canal system, and built the infrastructure to bring electricity to his town. And he did it all in just a little over a decade. About the time it would take today to get the permits for any single piece of the public works project.

Before Alexander and Florence Drake arrived, Bend was a rural outpost of just twenty-one souls at the turn of the nineteenth century. The Drakes had a vision of something grander.

“Alexander Drake came from money,” said Lisa Lee, historian with the Central Oregon Irrigation District (COID). “The elder Drake was involved in the railroad business and also served as a senator to the Minnesota senate.”

The Drake family fortunes took a hit in the latter part of the 1890s, in part thanks to two economic downturns and the railroad stock crash in 1894. The Drakes looked west to the frontier and saw opportunity. They left St. Paul, Minnesota for Portland, before finally settling in, what was then, Farewell Bend.

At the time of the Drakes’ arrival, Farewell Bend was barely a dot on the map. Engineer Levi Wiest helped Drake survey and map the irrigation canals for the federal government. In an interview with The Bend Bulletin on October 20, 1933, Wiest remembers a desolate place.

“There was only a little log schoolhouse in what is now Drake Park, a caved-in log cabin […] on the riverbank, and the Griggs deserted log cabin.”

Drake came to Bend to take advantage of the Carey Act of 1894. The Act gave investors a way to acquire public land if they could bring it under irrigation. With plenty of water on hand, Central Oregon was ripe for development.

In his book, Frontier Publisher, Jim Crowell writes, “Drake, even before leaving for the Far West, was familiar with the great economic potential of Central Oregon, especially its water resources, and soon after his arrival, he purchased land of his own.”

Entrepreneurial pioneers were already lining up to irrigate the desert land of Central Oregon. Charles Hutchinson formed the Oregon Irrigation Company in 1892. He had already filed a claim under the Carey Act but was looking to expand the footprint.

What happened next is murky, according to Lee. Hutchinson and Drake met at an irrigation conference in Spokane. Hutchinson was looking for capital to continue the expansion of his irrigation business.

“Hutchinson told Drake there were opportunities in Central Oregon and wanted Drake to join him as a business partner,” said Lee.

Only four months after arriving in Bend, Drake founded the Pilot Butte Development Company (PBDC). Days before the two “partners” were set to file the Carey Act paperwork, Drake cut Hutchinson out and filed the necessary documents as the sole owner of PBDC.

Drake received a state contract to sell the land and water rights and spent most of the next three years developing detailed survey maps for the future irrigation canals. But soon Drake was onto the next project. He sold his interests to Oregon Irrigation Company for $10,000 in 1904. (The equivalent of about $290,000 today.)

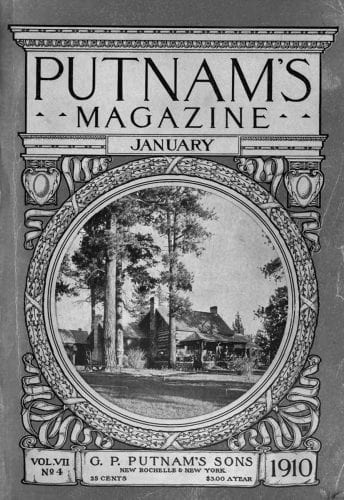

Drake’s vision for Bend did not end with plans to water the desert. Having helped spur an influx of settlers, Drake knew the growing town would need electricity, a commodity already enjoyed in large cities but scarcely found in rural areas. He founded the Deschutes, Water, Light and Power Company in 1909. He constructed a dam and powerhouse on the Deschutes at what is today Newport Avenue. While Drake sold his interest in the project before the lights came on in Bend, the work was a success. On November 2, 1910, the first electricity crackled through wires running from the powerhouse to business in downtown Bend, and 375 lights blinked on in the darkness.

As the father of Bend, Drake is credited with laying out one of the most picturesque townsites in Oregon, although that honor may go to his wife. In 1910, Drake hired a young civil engineer, Robert Gould, to start platting the townsite. Gould was assisted by Elmer Ward, who came to Bend the same year.

“Mrs. Drake loved every one of the cow trails on which these streets are located today,” said Ward in an interview with KBND’s Kessler Cannon in 1953. “She insisted that we locate the streets of Bend along those contours that formed the cow trails of those days. And we followed instructions. And that’s why we have the winding streets.”

The Drakes left Bend in 1911 for Pasadena, California—the same year that railroad tycoon JJ Hill hammered the last stake in the Oregon Trunk Railroad. The arrival of the rail line set off a second population boom and the construction of two massive sawmills that would transform Bend into a booming mill town for years to come. Drake wasn’t here to see the transformation, but he’d laid the groundwork for the town’s next phase of growth.

Drake died in his adopted hometown of Pasadena in 1934. The Bend Bulletin featured his obituary on the editorial page on October 12, 1934. The writer noted, “Had Mr. & Mrs. Drake chosen some other part of the west for their home, Bend might have remained Farewell Bend […] It was Mr. Drake who organized the Pilot Butte Development company, platted the Bend townsite and interested eastern capitalists in a community which, at the turn of the century, was merely a rangeland frontier.”

It seems fitting that the town’s crown jewel, the thirteen-acre Drake Park, bears his name. More evidence of fingerprints that time and memory may never erase.

Read more about the history of Central Oregon or more about our vibrant COMMUNITY today.