On a frosty February morning in Bend, the Deschutes River drifts into town, as ducks and geese move about on flat mud banks, exposed by lower winter flows. With temperatures in the 20s, it’s hard to picture the same stretch of river in warmer weather, crowded with innertubes and paddleboards, water flowing a bit faster and higher. By the time the water reaches the Old Mill District, the seasonal highs and lows are hard to spot to the untrained eye, and many would think the river is thriving and healthy. The Deschutes River is the lifeblood of Central Oregon after all—an economic driver, recreation hub, source of irrigation, habitat for fish and wildlife and scenic beauty. The river is dear to many.

Take a closer look at the beloved Deschutes, and it becomes the story of a hardworking river, stretched thin—simply not enough water for everyone hoping to get a bucketful, especially during an ongoing drought. The challenges of overseeing water in the Deschutes River Basin aren’t new, and most agree there are no simple fixes. But, a new Habitat Conservation Plan twelve years in the making provides a glimmer of hope and stability for the future of the river, promising more consistent flows and protections for Central Oregon’s fish and wildlife.

A voluntary effort by Central Oregon’s irrigation districts and the city of Prineville, working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service, the plan proposes that irrigators find ways to conserve water and stabilize seasonal flows in the river, and is part of an incidental take permit that will protect the applicants from endangered species litigation in the future. Irrigation districts agree the plan isn’t a comprehensive fix for the river, but believe it’s a great start, taking into account the needs of farmers, fish and wildlife, anglers, conservation groups and the public.

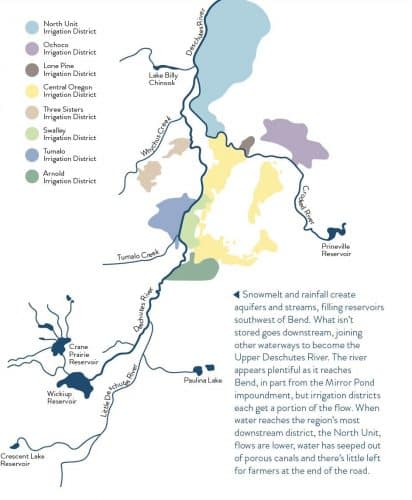

Central Oregon’s water woes are a product of historical practices that haven’t necessarily aged well. In the late 1800s, Congress passed the Carey Act, allowing irrigation companies to set up shop and sell water across the arid west, which a handful did in Central Oregon by 1904. Settlers were offered land in exchange for the cost of water, and irrigation districts followed the state water policy of “first dibs” that remains the foundation for water rights today. Those first irrigation districts established priority dates from 1899 to 1916, which dictate when and if their patrons receive water today. The process is straightforward but antiquated, without built-in protections for fish and wildlife and with no consideration for where farmers or other types of water users end up on the food chain.

When Michael Kirsch returned to the farm in Madras ten years after leaving for college and exploring other careers, his dad was there to guide him in operating the 2,000-acre family business. With about thirty-five employees to lead, crop rotations to consider and a budget to manage, Kirsch’s father told him the biggest focus would be on water. “He said the most important thing you’re going to do on this farm is irrigation management,” Kirsch said. This year, the budget calls for letting a third of the farm’s acres go fallow, sitting idle because of an anticipated lack of water for irrigation. It’s an increase from last year’s 28 percent, and a huge hit to the farm, which grows grass and carrot seed, peppermint for oil and seed potatoes, among other crops.

Like others in the North Unit Irrigation District, Kirsch has doubled down on water conservation at Madras Farms. “We implement drip irrigation practices, we have converted flood irrigation farms to sprinkler irrigation and we’ve installed ponds to catch runoff from one farm that is downstream from another,” he said. Kirsch sits on the North Unit board, and agrees with manager Britton that the district is among the most efficient in the state. “North Unit farmers have really been forced to be more efficient with the water they have, simply because they have less of it,” Britton said.

While farmers in the North Unit pride themselves on efficient water use, other landowners like those in the Central Oregon Irrigation District don’t feel the same pressure to use their allocated water so efficiently. If they use less water after all, they’re subject to the state’s “use it or lose it” water policy, so they’re encouraged to understand beneficial uses and use the water in appropriate ways each year. Part of Central Oregon Irrigation District manager Craig Horrell’s work is educating landowners about water policy, understanding beneficial uses, exploring conservation projects and sharing options for landowners who no longer want or need the water rights they have. One option is putting water back into the river with in-stream leasing. “We’re sometimes seen as a waste of water, but we’re making great strides and changes,” Horrell said. “We educate how to use water appropriately.”

With a limited amount of water flowing through the Upper Deschutes River each year, irrigation districts work to monitor reservoir water storage, control flows and ensure the water is divided properly among patrons. Water rights call for eighty-six percent of water from the Upper Deschutes to be diverted for irrigation, twelve percent to remain in-stream and two percent for municipal city use (think drinking water, laundry and showers). And while there are many important uses for water diverted, the Deschutes itself must retain some water for fish and wildlife habitats and community use, like fishing and recreation.

The Deschutes River was once called the “peculiar river” for its notably consistent flows throughout the year. But flows have been dramatically altered for the sake of seasonal irrigation, causing damage to riverbanks, according to Kate Fitzpatrick, executive director of the Deschutes River Conservancy. In the winter, water is stored in reservoirs to prepare for spring irrigation, leading to lower flows on the Deschutes. In the spring and summer, the flows are ramped way up for irrigation. “The flow regime of low flows in the winter and high flows in the summer has absolutely devastated the Upper Deschutes River,” Fitzpatrick said.

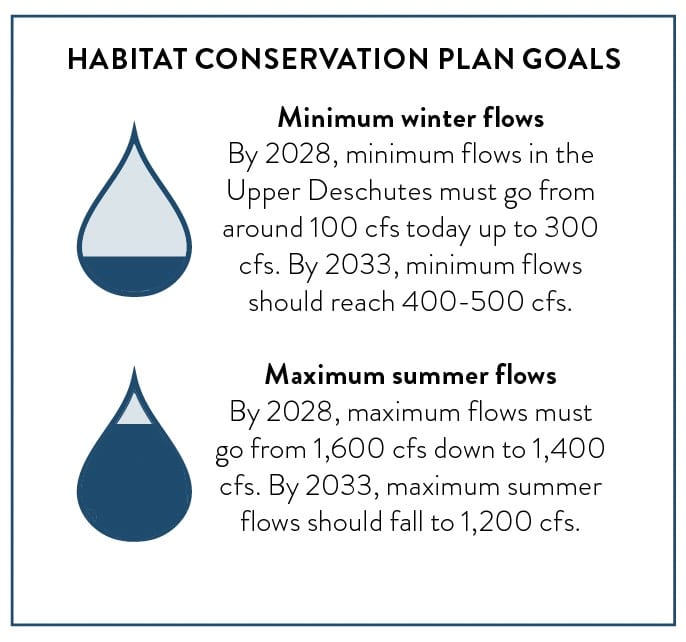

Seasonal swings were so significant in the early 2010s that flows in the Deschutes were as low as 20 cubic feet per second in the winter and as high as 1,800 cfs in the summer, dictated by climate conditions, dams and water storage practices and irrigation needs. During low flows, fish habitats like those for redband trout are degraded, riverbanks eroded and silt deposited into the river. High flows widen the riverbanks, wash away fish eggs and cause further habitat damage. For the Oregon spotted frog, low river flows have resulted in the loss of many of the once-common frog’s river side-channel habitats. “They’re just hanging on in a few places, where they would have been distributed throughout the river abundantly,” said Noah Greenwald, endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

For fish, erratic highs and lows in river flows affect survival of fish species, and lessen opportunities for recreational fishing. “We need clean, cold water to sustain trout, and if you lower the river enough it’s not as clean and it’s not as cold,” said Tim Quinton, president of Central Oregon Flyfishers, a nonprofit group that promotes catch-and-release fly-fishing, river restoration projects and youth outreach. Quinton recalled a fishing trip to the Crooked River in the winter of 2015-16 when the winter flows had gotten so low, portions of the river were ice from top to bottom. “Obviously fish can’t live in ice,” he said.

The Deschutes River Conservancy and other conservation groups pushed for years to collaborate with irrigation districts in an effort to stabilize seasonal flows, but concrete change never came. In 2007, an effort to re-introduce threatened steelhead in the Upper Deschutes Basin kicked off a process to create the new Habitat Conservation Plan, which aims to ensure irrigation needs on the Upper Deschutes are balanced with fish and wildlife and river health. In recent years, it was the spotted frog that became the impetus of a lawsuit brought on by environmental groups, who argued that irrigation districts in Central Oregon and the Bureau of Reclamation had violated the Endangered Species Act through irrigation practices that harmed the frog’s habitat, and failed to consult with relevant agencies.

In December 2020, twelve years after work on the Habitat Conservation Plan first began, a final draft was released, gaining approval from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The plan puts forth a thirty-year roadmap for stabilizing flows in the Upper Deschutes to lessen such dramatic highs and lows in the river, improving conditions for the spotted frog and various fish species.

Irrigation district leaders are optimistic about the plan, as it lessens the possibility of litigation bringing forth sudden changes in water supply for their patrons, and offers for the first time a real commitment to the future of the river. “There’s accountability,” Horrell said. “I think that’s the big thing. We finally signed on the line and have accountability to put water back in the river and do these projects.”

To accomplish the goals set forth in the Habitat Conservation Plan, irrigation districts must find ways to conserve water, one of which is through large-scale piping projects to modernize delivery systems and prevent water loss. In the Central Oregon Irrigation District, as much as fifty percent of water is lost to seepage through porous lava rock canals, so piping can improve efficiency in the district and free up water for other uses or a return to the river. It’s costly, however. The district plans to undertake as much as $100 million in piping projects over the next ten years, starting with a 7.9-mile stretch of pipeline between Redmond and Smith Rock. That $33 million project is estimated to put 33 cubic feet a second of water back into the Deschutes.

Federal grant money to help pay for piping is attractive to irrigation districts, but shouldn’t be their only focus, according to river advocates like Tod Heisler, rivers conservation director for Central Oregon LandWatch and former executive director of the Deschutes River Conservancy. Heisler would like to see irrigation districts focus more on true conservation of the water—teaching landowners to irrigate more efficiently and offering incentives to do so, or further developing a water market, where patrons with water rights can lease their allocation to farmers in need or send it back into the river. “It’s very evident that most of their time and effort and focus has been spent on designing and working on this big modernization plan and piping their district,” Heisler said. “But they should still set higher standards—you can’t pipe your way out of a problem for a species that you helped create a threat for.”

Horrell said the district is focusing on more than just piping, with efforts to increase in-stream leasing and encourage on-farm efficiencies. But large piping projects are important too, he said and will give the district a solid infrastructure for the future. “In order to make a change for a long time, we have to invest in the district,” he said.

As of early February, the Habitat Conservation Plan was still under review by the National Marine Fisheries Service, a final cooperating agency that will weigh in on the plan for improvements in the Deschutes River Basin. The more consistent flows that will be achieved as part of the plan are a notable improvement from current river conditions, yet environmental groups worry that the process is taking too long, and that the Habitat Conservation Plan doesn’t spell out exactly how the goals will be achieved. “From our perspective, we have a lot of concerns,” Greenwald said. “Our primary concern is we’re going to get to year eight, and they’re going to say ‘we can’t do this.’”

While the plan doesn’t require higher winter flows on the Deschutes until 2028, a more gradual increase in flows as conservation progress is made is possible, too. “I’m an optimist and I see this as an incredibly positive thing for the Deschutes River, with accountability that’s never been there before,” said Horrell, who has lived and worked in Bend for twenty-three years, the last seven leading the Central Oregon Irrigation District. “Growing up in Oregon and coming to Central Oregon all my life, I’m so excited to see this change in the health of the river.”

Although the plan wasn’t created to address drought conditions, it offers a sense of stability to farmers like Kirsch, who hopes to continue his family farm for decades to come. He’s hopeful that through the steps outlined in the plan, and ongoing conservation efforts across the region, his farm will have a stable source of water, and hopefully more of it, in the future. “It’s never going to be perfect for the farmers, or the recreational group or the fisherman—but we’re all in this together and we need to find ways to make this work,” said Kirsch, who also fishes and enjoys rafting. “As you get older, you learn to really appreciate the river and how it does affect so many people. The water is for everybody, as long as it’s maximized to its fullest potential.”