The Deschutes Railroad War is A Race for Oregon’s Natural Resources

The Deschutes River Railroad War in the early 1900s shaped the future of Central Oregon. Without railroad tycoons James J. Hill’s and Edward Harriman’s animosity towards each other, the area would look different than today. The battle royale played out along the steep river banks of the Deschutes and in the courtrooms of Portland.

On paper, Central Oregon was considered a high desert. However, the landscape held an important commodity—water was a necessity to irrigate the parched land. It also held another important commodity. In 1905, Israel C. Russell with the U.S. Geological Survey issued a report, Geology and Water Resources of Central Oregon, extolling the natural resources in the area: “The yellow pine forests [in the] central part of Oregon are not only extensive, but contain magnificent, well-grown trees, which will be of great commercial value when railroads shall have been built.”

The possibilities of getting a railroad into Central Oregon seemed bleak in the early 1900s. In his book, In the Oregon Country, George Palmer Putnam described the area as a “railless land, the largest territory in the United States without transportation.” At the time, Putnam had yet to purchase The Bend Bulletin or become Bend’s mayor. Nonetheless, he was a booster who believed that the area’s farm and timber products were worthless without a way to market. As he put it bluntly, “In Central Oregon the railroad question was one of life and death.”

That changed in 1909 when Hill and Harriman decided to build two separate tracks up the Deschutes River.

Two Men and Two Railroads

Although Hill and Harriman interacted professionally during their business dealings, privately, they despised each other. In 1901, Harriman tried to corner the market of Northern Pacific to gain voting power in the company controlled by Hill. The take-over failed and ended in a near stock market crash. “Hill and Harriman were interested in connecting with the Central Pacific route which had reached Klamath Falls by that point,” said Paul Claeyssens, owner of Heritage Stewardship Group in Bend. “They wanted to open the markets from the east side of the Cascades to California.”

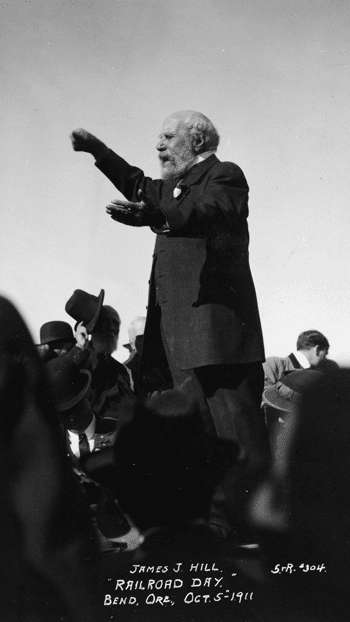

Russell’s report about Central Oregon must have whetted Hill’s and Harriman’s appetites. Whoever won the “war” would see a hefty return on investment. Hill got standing ovations when he visited Portland’s Lewis & Clark Exposition in October 1905. He had just announced plans for the construction of the North Bank railroad along the Columbia River. He would finish the line in February 1908 as a stepping-off point towards Central Oregon.

Harriman incorporated the Des Chutes Railroad in 1906 with the expressed purpose of building a line into Central Oregon. Two years later, Harriman was far from ready to start construction. For many Central Oregonians, the issue could be summoned up as; “Harriman promises. Hill builds.” Finally, by mid-1909, Hill and Harriman, egged on by each other, started construction.

The Race Was On

The most efficient way into Oregon’s interior went up the Deschutes River from The Dalles, where both Hill and Harriman had existing tracks. Hill’s engineer and president of the Oregon Trunk Railway, John F. Stevens contracted the Porter Brothers to build on the west side of the Deschutes River while J.P. O’Brien contracted the Twohy Brothers to lay Harriman’s tracks on the east side. Perhaps influenced by Hill and Harriman’s feuding, the work conditions almost immediately became hostile. “The blame for the infighting lays mostly with the supervisors who created an atmosphere of conflict,” said Leon Speroff, the author of The Deschutes River Railroad War.

Delay Tactics

The construction camps were small, semi-permanent tent cities along the riverbanks. The work was backbreaking. Evening entertainment, fueled by plenty of moonshine, included taking potshots at the opposing crews or performing brazen raids across the river to steal black powder or simply blow it up to delay construction. Revenge operations saw crews stampeding each other’s beef cattle. “There’s no evidence that the competition accelerated to the point where they were actually killing each other,” said Speroff. “They were just trying to scare people.”

One of the more ambitious schemes was an attempt by Steven’s crews to block access to the Twohy brothers’ water supply. The wagon road went through a nearby 320-acre property. Stevens allegedly bought the property, put up “No Trespassing” signs, and posted armed guards.

In September 1909, when the local sheriff arrived to solve the dispute, fighting broke out between Porter’s and Twohy’s work crews. During the melee, the sheriff and his deputies were ejected, and their horses were sent running into the high desert. The dispute had to be resolved in court.

Reaching the End

Throughout the project, Hill and Harriman’s representatives fought ongoing battles in Portland’s courtrooms. “You get the impression that much of the ‘war’ played out in the courtrooms. Ultimately, Stevens and his group had better lawyers,” said Speroff. After the death of Harriman on September 9, 1909, Hill and Robert Lovett, Harriman’s successor, decided to play nice.

The Harris track-laying machine reached Bend on September 30, 1911. The finished line included 151.5 miles of tracks, seven tunnels, and ten steel bridges—including the Crooked River High Bridge and Hill’s Columbia River Bridge. In the end, Bend was the real winner of the railroad war.