Warnings everywhere to wash hands. Fever monitoring. Quarantine. Events cancelled, theaters closed and a massive push for a vaccine. It may sound like the stuff of 2020, but it played out across America before, and not all that long ago. 1952 was the peak of the country’s polio epidemic, which resulted in decades of crippling and deaths for thousands.

Like coronavirus, the first major outbreak of polio in the U.S. struck in New York, in 1916. The scourge spread west, gripping the country with fear along its trajectory. Polio didn’t spare its wrath in Central Oregon, a small, tight-knit timber town with a fraction of the population it has today.

“We were like the entire country,” said Kelly Cannon-Miller, executive director of the Deschutes County Historical Society. “From 1915 to 1955, every summer was polio season. Every summer, parents were afraid. Boomers now in their 70s and 80s remember their parents checking them for fever, intestinal discomfort, any sign that their arm, leg or neck was not moving right.”

During polio season, health officials employed many of the same tactics as those used to flatten the curve of COVID-19. The two viruses also share the insidiousness of ability to spread by people who have no symptoms of the illness, but who carry and transmit it.

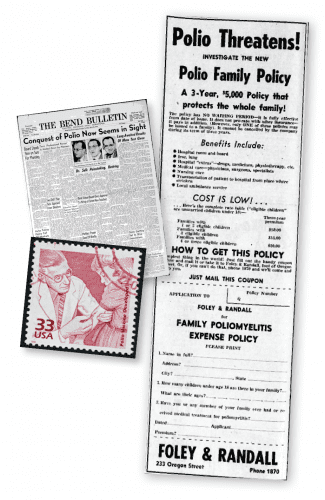

Panic around polio began in the late 1940s, as outbreaks in the United States grew, mainly targeting children, although perhaps the disease’s most famous victim was an adult, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The epidemic reached a crescendo in 1952, when about 58,000 contracted the disease and more than 3,000 died.

The race for a vaccine was on, led by the March of Dimes, which recruited millions of volunteers who collected dimes in cans and raised hundreds of millions of dollars for the cause. By 1954, with the grassroots movement funding the research of Dr. Jonas Salk, nearly two million school children participated in the vaccine’s field trial. Starting on April 26 of that year in Virginia, it was the largest medical experiment in history.

Polio plays out in Bend

Across the country a few weeks later, George Ray was celebrating Father’s Day in Bend with his wife, Shirley, and their 2-year-old daughter, Myrna. George, 27, had been promoted to a sales job at one of Bend’s major timber firms, Leonard Lundgren Lumber Company. He’d worked his way up from jobs in the woods and on the “green chain,” pulling boards out of the sawmill, and now had the chance to leverage his degree from Oregon State University.

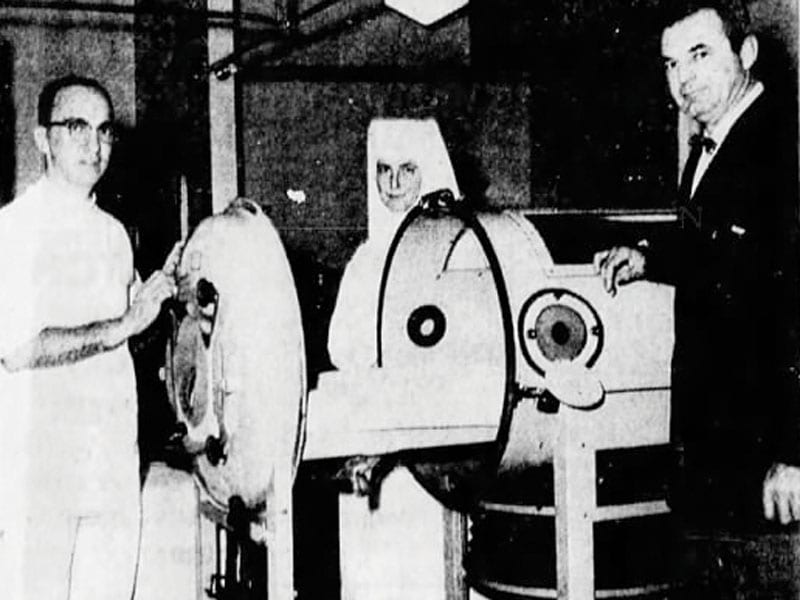

Shirley told him to treat himself to some fishing with a buddy that Father’s Day, and that night they went to the drive-in to catch The Moon Is Blue, starring William Holden. The next day, George told Shirley he was feeling achy. By Tuesday it was worse. By Wednesday he was in St. Charles Hospital and quickly transferred to Portland, where doctors were more experienced in treating polio. Paralysis struck his legs, arms and respiratory system. Doctors slid him on a cot into an “iron lung,” a long metal tank respirator, the precursor of the modern ventilator.

By fall, Ray was able to breathe on his own and return to Bend. Undaunted by his paralyzed legs and left arm, he returned to work. His new sales job was done mostly by phone and he had enough strength in his right arm to use one. He couldn’t push himself in his wheelchair, but after reading a magazine article about the latest electric model, he eventually found one, said his daughter, Myrna Ray Klupenger, who now lives in Florence, Oregon.

Polio may have stolen her father’s mobility, but not his entrepreneurial skills or the dedication of friends—making possible his civic involvement and philanthropy which reverberates through the community to this day. One of those friends was Norbert “Blackie” Schaedler, a mechanic at the Lundgren mill.

“He designed Dad’s little red car,” Klupenger said. The electric, three-wheeled vehicle, inspired by a golf cart, was level to the curb so Ray could roll his wheelchair onto it. The steering wheel was like a boat tiller which he could operate single-handedly.

“It was amazing,” Klupenger said. “It was completely open to the weather—Mom would bundle him up. It had a strap kind of seat belt and he went off to work on his own. There was a seat in back for me and Mom. People all over town knew him and that little red car and he went to all the football, basketball and sporting events.”

Schaedler also devised a lift with straps that could carry his friend from his wheelchair to the family station wagon, his bed and bath. Ray became an independent lumber broker and partnered with another friend from the mill in opening a lumber yard. Shirley worked full time, managing The Pine Tavern restaurant, co-founded by her aunt, Maren Gribskov. “They decided to live on one income and save the rest, and Dad liked the stock market,” Klupenger said. “They were wise investors and not spendthrift.”

The Rays supported St. Charles Hospital and Shirley organized local fundraisers for the March of Dimes. After George died of pancreatic cancer in 1988 at age 61, Shirley continued supporting local nonprofits including the Central Oregon Community College Foundation, Cascade Culinary Institute and OSU-Cascades before she died in 2018 at age 91.

“Shirley Ray’s philanthropy is becoming legendary now, but they were very quiet about it,” said Cannon-Miller.

Cannon-Miller reflected on the era before vaccines eradicated so many diseases. “We have lost our use and practice of quarantine as a first line of defense,” she said. “Modern medicine has made that largely unnecessary for humans for several decades now. It’s harder for us to accept and understand what’s happening because we’re out of practice. We haven’t had to do this for a very, very, very long time.”