Over the past fifty years, Bend has grown in short, intense bursts. This time, it means growing up or growing out. Are we ready?

Graphics by Brendan Loscar | Chalk art by Katey Dutton

On July 15, a dozen people packed the Bend City Council meeting. Determination radiated from their florescent yellow shirts whose bold capitals proclaimed, “Save Pilot Butte.”

There was no insidious plan to close the butte, or strip it of its junipers or pave it over with a new road. What Pilot Butte needed saving from was growth in the form of an apartment complex planned for a nearby neighborhood. This proposed 205-unit apartment complex would add to the scarce inventory of available rental housing and likely offer affordable homes to some of those families in Bend’s growing population.

At this council meeting, there was little solidarity from a renter in another nearby apartment complex. “I don’t believe that the four-story apartment complex is the best, efficient use of that land,” said Hope Dalryample. “[Our street] already has parking problems as it is. Our lease is month-to-month, and if they do the construction, our plan is to move because it is just going to be unrealistic to get out of that parking area.”

Dalryample’s voice, shaky with nerves at times but determined nonetheless is increasingly the voice of many Bendites who weathered the recent recession and now see a city ready to explode with growth once again.

Urbanization, in-fill, and density are all themes in play as Bend contemplates its larger self. No matter what moniker it goes by, change—significant change—is on the cusp. Central Oregon, and Bend in particular, will look very different in the coming years.

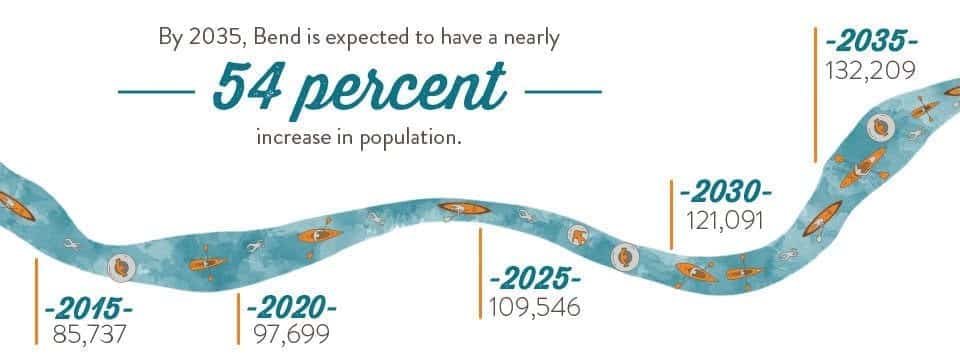

Multi-storied buildings and other housing density projects will soon be planned for neighborhoods in the southeast, the northeast, the downtown core and every other section of the community as Bend seeks to accommodate a projected 54 percent increase in population over the next twenty years while balancing a state mandate to keep the city’s urban growth boundary tight around the waist.

“It’s in the cards, and it’s not going to be easy,” said Nan Loveland, one of the founders of Old Farm Neighborhood Association in southeast Bend who, at times, has closely scrutinized developments near Pilot Butte and sees the “Save the Butte” group as an inevitable harbinger of growing conflict. “[This apartment building] is going to add more people, it’s going to change the nature of how the area looks,” Loveland said. “Residents have had open spaces for a long time. People just don’t like change. Very few people embrace it.”

POPULATION

“We just wanted to live here. We felt the draw for so many years and to have the door open up for us, we just couldn’t say no.”

– Rachel Scott

Loveland, who moved to Bend in 2000 after retiring from a teaching career, was part of an earlier wave of Bend’s population growth—a boom that increased Bend’s population nearly 70 percent between 1995 and 2000.

Trevor Scott, 28, is part of a new influx that is being driven by recreation and new industries, particularly high-tech. Trevor and his wife, Rachel, 26, moved from California to Bend in June for his new tech job with Five Talent, an app and software development company. She left a steady job as a risk analyst with Ventura County, where she had just earned a promotion. The couple packed up their studio apartment in a desirable neighborhood just a mile from Ventura Beach and headed for Bend, even before finding housing.

“We just wanted to live here,” said Rachel. “We felt the draw for so many years and to have the door open up for us, we just couldn’t say no.”

They came for the love of the outdoors, skiing at Mt. Bachelor and to be closer to family, who live in Northern California. The young couple knew it would be difficult for Rachel to find another job, and that affordable housing in Bend was scarce, yet they believed it was the right thing for their family and first child.

“The conversation basically came down to, ‘Do we want to be semi-comfortable in Ventura or live somewhere where we actually want to live and risk being slightly less comfortable?’” said Trevor.

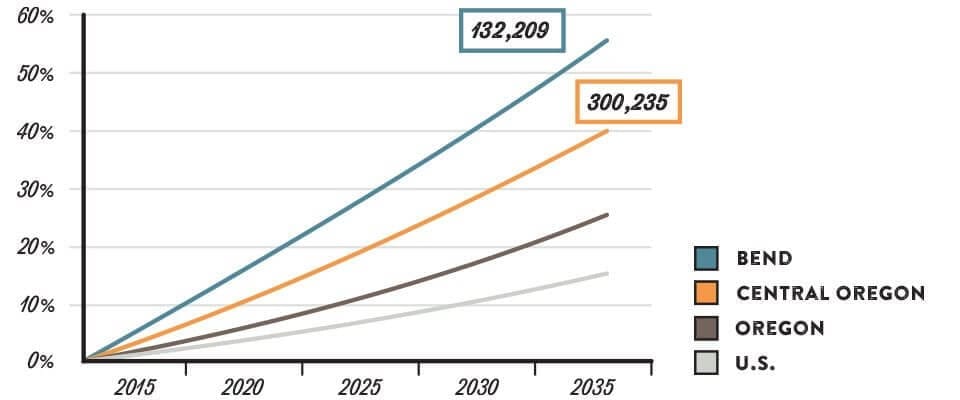

This quality-of-life debate, chiefly among millennials and seniors, is expected to result in an additional 46,500 people migrating to Bend by 2035, increasing the population to 132,200. This growth is expected to outpace the rest of Oregon, the West Coast and most areas across the nation.

“Boomers and the millennials are the dominant market in Bend to the mid-2030s,” Arthur C. Nelson, a professor of urban planning at the University of Utah and a nationally recognized demographer, told the Bend City Council and the City Club of Central Oregon in July. “What these two groups want will help spur the coming changes in how people live and get around in Bend.”

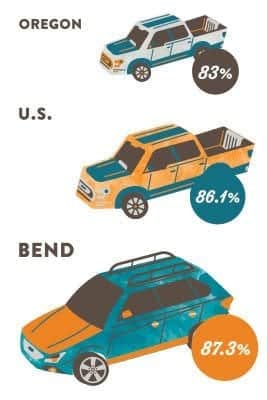

Fewer millennials, now 20 to 35, are opting for the quintessential single-family home on a suburban lot. Likewise, seniors are, increasingly, looking to downsize to smaller homes, condominiums or apartments. Both groups favor walking, biking and public transit.

“This will lead to a decline in home ownership,” said Nelson. “Basically forty percent of all new demand will be for rental housing. A much higher share of all new housing going forward to 2040 is going to have to be different. And these groups will be looking for more opportunity for walking and biking.”

HOUSING

In an attempt to slow urban sprawl and maintain farmland and forests, Governor Tom McCall, in 1973, signed a progressive land-use bill that mandated a twenty-year supply of land for housing and economic development for every city in Oregon. McCall, in a passionate speech, decried, “sagebrush subdivisions, coastal condomania and the ravenous rampages of suburbia.”

The relationship between the state-regulated UGB and the City of Bend has been that of teacher and student. In 2010, the city submitted a plan to the state Land Conservation and Development Commission to expand its boundary by 8,400 acres—the first proposed expansion since 1981. The state rejected the application for its failure to first show how it would use existing space within the city efficiently.

The overriding message from the State of Oregon to the build-first predisposition of Bend was that density must precede sprawl. Now the city is planning for an expansion of around 2,000 acres with a focus on using land currently inside the UGB differently. It’s likely that this philosophy, more than anything else, will shape Bend’s cityscape over the next fifteen years.

Behind this prescription is the notion that the largest tracts of undeveloped land, such as those in southeast Bend where Loveland lives, will be rezoned and subdivided to usher in a greater density of residences. At the same time, the city will look to create incentives for new development on small infill lots inside existing neighborhoods throughout town. For example, the Bend City Council recently eliminated the need for expensive conditional use permits for new duplexes on corner lots.

That single change immediately triggered a fuss in Bend’s West Hills, where a developer began building a multi-family home in an area surrounded by single-family houses. Homeowners took to an online forum called Nextdoor to vent their frustrations with the new project.

“I need some space around me but still be within walking distance of amenities and be able to meditate while looking at the mountains,” wrote one West Hills resident in the thread relating to the new duplex. “I have lived down in the flats, and it was a lot noisier.”

“Although I enjoy the convenience of living in town, the thought of leaving the city, or buying a larger parcel within, crosses my mind every day,” wrote another resident. “ … The unfortunate fact of the matter is that there are too many people who want to live in Bend, to build every residence a typical single story with a quarter-acre or more.”

This frustration over new development in the city isn’t a new problem. From her single-family home off of Ferguson in southeast Bend, Loveland looked out of her sliding glass door on a recent afternoon and described how she and a dozen other residents were able to persuade the city to reduce the number of lots that a nearby tract was subdivided into about a decade ago.

“That subdivision was going to go in with sixty-eight homes—it was going to be high residential,” she said. “That left (some neighbors) with five new homes along their lot line. So a bunch of us got together and hired Paul Dewey as a lawyer,” Loveland said, referring to the executive director of Central Oregon Landwatch, a group that encourages smart growth. “We got it down to thirty-eight.”

Despite Loveland’s earlier success in shaping development, she isn’t sure how new rules currently being drafted by the city’s planning commission will affect new higher-density residential projects abutting existing neighborhoods.

“My concern is that the new language will have protections for RL, the lowest density zoning, but what happens when you put these big lot residential single-family lots up against residential medium density lots or residential high density lots?” Loveland asked, speaking in the vernacular of developers gleaned from her involvement in civic committees and land use. “How do we preserve the character of these old neighborhoods?”

As the UGB expansion marches forward, the key to achieving this will be community input. “Involvement is a big key—it’s a huge key,” Loveland said. “You have to spend the time to learn what the problems are, who the players are, and how you can influence things, what you can bring to the table that might be helpful.”

TRANSPORTATION

Crumbling streets, an incomplete sidewalk grid, dangerous bike and pedestrian routes and a fledgling transit system that runs just six days a week and stops at 6:15 p.m.—this is the current state of Bend’s transportation system.

Now picture another 25,000 cars here by 2030 with virtually no new roads, the addition of a university, and the realization of denser residential housing.

A tally of the cost of projects for improvements to transportation run more than $100 million, plus ongoing annual funding of $5 million or more to operate the public transit facilities.

What sounds like a system doomed to failure could actually be the seed of a solution to Bend’s transportation issues, said Robin Lewis, transportation engineer with the City of Bend. The more congested the streets, the more people are willing to consider alternative modes of transportation. For investments in key multimodal infrastructure such as public transit to pencil out, more people have to be willing to regularly take the bus.

In the coming months, as part of the UGB process, the city will begin changing zoning and development rules to create incentives for developers and residents to embrace supporting alternative modes of transportation.

In fact, earlier this spring, the city reduced parking space requirements for residential developments near a transit line, in the hopes of encouraging more development near transit lines and to coax future residents to take public transit.

Moves like this could encourage people to live along “transit corridors,” which will become the skeletal structure for higher density areas throughout the city. Greenwood Avenue, Third Street, Reed Market Road, and other major streets will eventually offer the multimodal transit, bike and pedestrian facilities that will allow the city to better accommodate growth with fewer cars.

These changes, however, imply a change of culture and a substantial influx of funds. A tally of the cost of projects for improvements to transportation run more than $100 million, plus ongoing annual funding of $5 million or more to operate the public transit facilities.

Earlier this year, David Abbas, the street maintenance director for the City of Bend, said that city streets have declined to a “D” level and the city is facing $80 million in deferred maintenance. Compare that to Deschutes County and Redmond, which have maintained streets at a “B” level.

The deferred maintenance is the result of at least a decade of political and administrative instability, said Bend City Manager Eric King. From 2000 to 2007, Bend had four city managers and a great deal of turnover on the city council. To tackle large infrastructure issues during that time was very challenging, he said, and earlier attempts to fund roads were voted down by the city council.

“These are not easy things,” said King. “There have been efforts to educate the council on these issues, and sometimes there is political will for it and sometimes there’s not.”

Loveland watched it happen from her position on the city’s infrastructure advisory board, where she served for years. “The hard thing for Bend is that we are playing catch up,” said Loveland. “The decisions were not made thirty years ago when they should have been made.”

Because of the constraints of Oregon’s Measure 50, the funding mechanisms to catch up are few and local. Twenty-three cities across the state have navigated this issue with a local fuel tax, another thirty-one have passed transportation utility fees—which are frequently tacked onto water and sewer bills.

In August, Bend City Councilors, in a four-to-three vote, agreed to open up the debate of a local fuel tax to Bend residents by putting the issue on the March 2016 ballot. Passing it will be tough, with formidable opposition likely from a group of local petroleum dealers, which has hired Bend’s former mayor, Jeff Eager, to lobby against the tax on their behalf.

But the city has other options for raising transportation money. It could ask the public to pass a food and beverage tax that would seek to capture more tourism revenues from the roughly 2 to 3 million Bend visitors each year. The city also has plans to lobby the Oregon Legislature to pass a studded tire fee or new vehicle registration fee.

While funding roads in Bend is challenging, the real question is whether the city has strong enough political leadership to address the issue and adequately frame what’s at stake for its residents.

FOR Trevor and Rachel Scott, Bend’s future looks promising, but they are concerned whether the city they chose will be a good long-term bet. They wonder if voters will continue to fund schools with new levies. Will there be local employment opportunities for their daughter to stay in Bend when she is of working age? Can the small-town charm be preserved in the face of growth?

“It does seem like it’s on the cusp of something,” said Trevor. “I couldn’t tell if it would be negative—it seems like it would be positive.”

Meanwhile, many longtime residents resent the influx of newbies and change.

“Everybody has lived in rental housing at one point or another in their lives, but they don’t see the individuals for the whole,” Loveland said. “They don’t see the individual college student coming in, they just see the hordes.”

Click to read more about the Central Oregon BUSINESS community here.