A surge of interest in contrast therapy has made it easy to unleash your inner Viking.

Frankly, I think they’re bonkers. Some friends and I are seated in a sauna sweating our cheeks-to-cheeks off. It’s a cold, brittle day in Ramsvik, Sweden, and the oven-hot air inside here has that spicy cedar scent. My leg muscles, tight from a morning trail run, now go slack like molasses in the sun.

“You ready?” prods my friend Jim, motioning toward the sauna door.

The sauna sits along a small cove of black, 43-degree seawater, which is a whopping 160 degrees colder than inside the 200-degree sauna. Jim wants to race outside and do a cold plunge. The Vikings themselves knew this kind of hot-cold routine could bring curative, transformative powers. To me, it sounds like torture.

“I don’t know,” I say. But peer pressure prevails and into the water I go.

You know what happens next. I freak out. The cold crushes my breath into sharp, inefficient gasps. The water drains the heat from me with lethal efficiency. Every brain cell tells me to get out of this, now. I do as Jim says and work to control my breathing. When I do, something odd starts to happen.

I find willpower. Time slows and thoughts go still. I stop reacting to the pain and let my mind feel it out, like a finger drawn on an old stone wall. For a moment, I’m in control.

In less than a minute survival instincts take over and guide me out of the water. Dripping wet in the icy breeze on the dock, I am neither hot nor cold but sharp and alert like never before. I feel like a guy who has learned he can fly.

Cold Plunge as Therapy

Scandinavians have long embraced the sauna-plunge ritual of vinterbadning, or winter bathing. But now “contrast therapy” is everywhere. In Bend, you could even say it’s having a moment.

Consider this. Gather Sauna House: The original sauna/cold plunge business in Central Oregon is in its third year of a partnership with Bend Park and Recreation District. Its setup at at Riverbend Park allows you to sweat in a wood-fired sauna only steps away from a plunge in the chilly Deschutes River. Founded in 2019, Gather Sauna House will soon add a brick and mortar spot in addition to its seasonal park location. In late December 2024, SweatHouz opened on SW Century Drive with cold plunges and infrared saunas that warm tissues with a deeper heat. ChillWell opened in September 2024 on Olney and Wall streets. Flux Thermal Lounge in the westside Century Center will open in 2025 to provide hot and cold water immersion therapy. Bend’s mobile barrel sauna and cold plunge service, 541 Social Club, found a permanent home at Foundation Health and Fitness in southeast Bend.

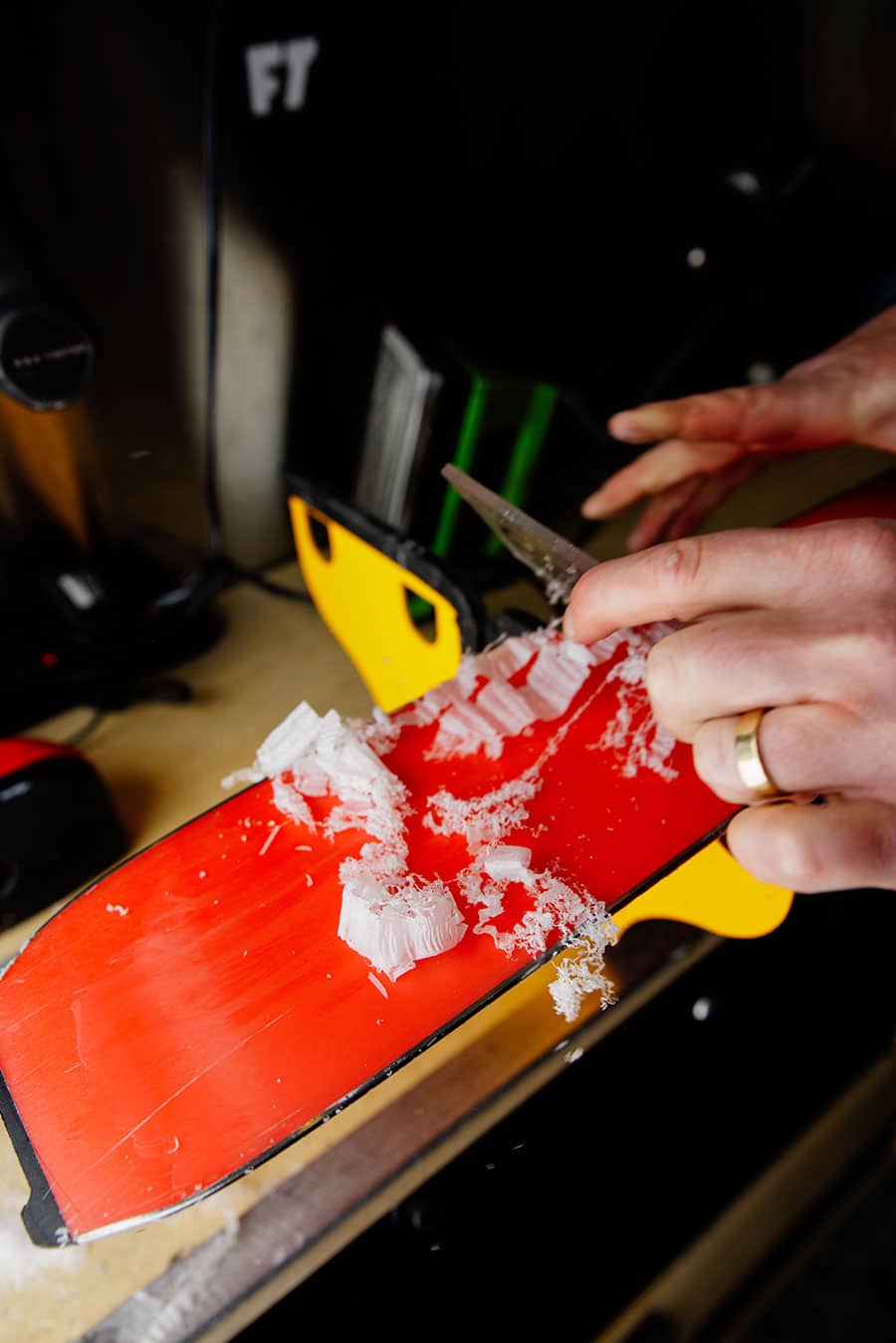

Want to build your own? Redmond Spa Stove and Sauna has the heat. For about $15,000, Redmond-based BlueCube will make you a handcrafted tub cooled by commercial chillers.

“People are digging it,” said Bryan Messmer, a former self-described contrast therapy skeptic who tried it, had a wonderful, transformative experience and launched ChillWell. “I thought for sure I was going to see a bunch of yogis and granolas and endurance athletes and biohackers and those kinds of people, but that has not been the case,” Messmer said. “This has been for everyone.”

From the Athletes

For years, athletes everywhere have fought muscle soreness and fatigue with cold therapies while others have sought the mental and physical benefits of cold plunges and breath work championed by people such as surfer Laird Hamilton and Wim Hof—the Dutch “iceman” known for his acts of enduring extreme cold. With this flush of new services in Bend, anyone can book a session and hire an expert to guide them through the experience.

Clayton Reeves, a Mountain View High School grad and an Oregon State Beaver with a bachelor’s degree in exercise sports science, is one of those experts. He returned to Bend after seeing a need for a mobile contrast therapy service. By January 2023 he was rolling around town with a barrel sauna and cold plunge tubs on a trailer that he could set up outside of gyms. He showed up at corporate retreats and marathons. Often people would hire him to do private pop-up events on their neighborhood streets.

“So many people would stop me and be, like, is that wine?” Reeves said. “I’d say, ‘No, it’s performance recovery.’”

His new space at Foundation Health and Fitness is now fully enclosed but the benefits are the same. How hard you train is only as beneficial as how well you can recover, he said. Alternating between hot and cold can speed that up.

For the hot portion of contrast therapy to work best, Reeves said you need an environment that’s at least 170 degrees. That’s when our cells activate a flood of heat-shock proteins that cruise around the body looking for and repairing damaged cells. The heat also ups your heart rate, which ups your blood flow and results in faster repairs. A sauna also stress tests our abilities to sweat, which trains our bodies to cool themselves more efficiently in the future.

Adding in cold is when things get interesting. Getting into water that’s roughly 40 degrees drastically reduces inflammation throughout the body, slashing pain. Cold-shock proteins whirl to life and pick up the repairs. Feel-good neurochemicals such as dopamine, adrenaline, epinephrine and oxytocin surge into the blood stream giving us a euphoric rush. To warm ourselves back up, our cells incinerate “brown fat,” a healthier fat than the “white fat” that’s great for the brain. The hot-cold combo can leave you in a better mood with less stress and anxiety and more confidence to face new challenges. “Plus I sleep like a baby,” Reeves said.

Me, too. Not long after I get home from Scandinavia, my wife and friends book a session at Gather Sauna House. I’m tempted to try it again, but ultimately chicken out. My wife struggles to push through the pain, while another friend, Erin Morgan, is hooked. She lights up when I ask her about it a few days later.

“I feel like that yoga shirt that says, ‘I’m just here for the Shavasana,” Morgan laughs. “Bring it on.”