Routing the Climbing Course

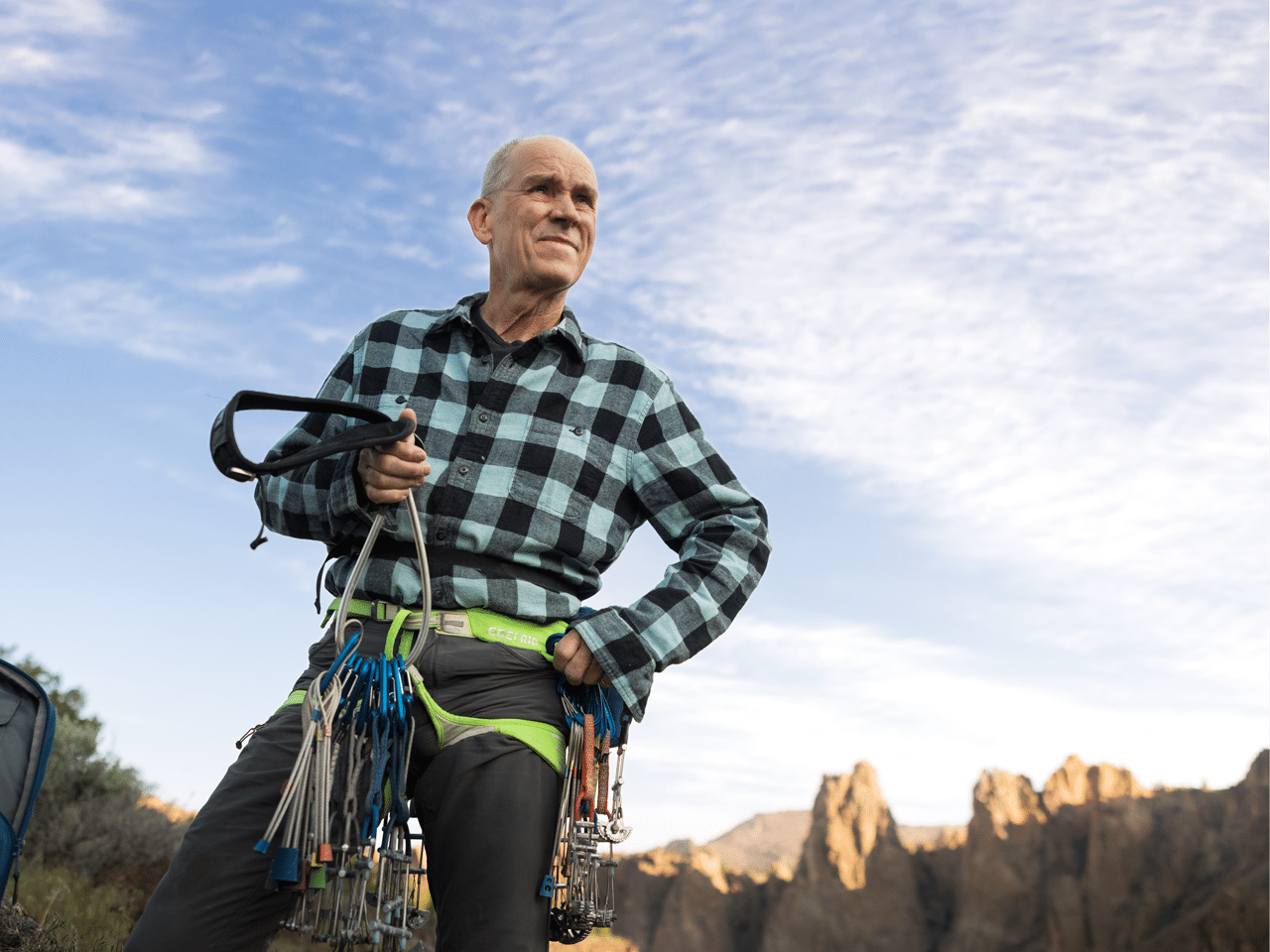

It’s late morning as Alan Watts pulls up at Smith Rock State Park. We first climbed here almost 40 years ago, when Watts was establishing a new style of rock climbing and putting Smith Rock on the map. We’re older now and not climbing as hard as we used to, but that’s OK. Today we’re going to climb a few forgotten classics, hoping we’ll have them to ourselves. We put on our packs and start hiking down the Chute Trail. That’s when it starts. [Above photo by Jules Jimreivat]

“Are you Alan Watts?” someone asks. “Will you autograph my guidebook?”

I like climbing with Alan, but we never do a lot of actual climbing. It’s like hanging out with a rock star. Everyone stops him to chat, pose for a selfie or autograph his climbing guide (he gets so many requests he carries a Sharpie in his pack). He’s been climbing here since the mid-1970s; when it comes to Smith Rock climbing, he wrote the book. His popular climbing guide, first published in 1992, is in its third edition.

I first climbed at Smith in the early ‘80s and was not impressed. Sure, the park inspired a sense of awe (it still does), but the rock seemed loose and the climbing so-so. I didn’t know that Alan—then a self-described “scrawny kid from Madras” in his early 20s—had already put up the first of dozens of steep, bolt-protected routes on the park’s blank-looking walls that would transform it into a world-class climbing destination. After a picture of Watts appeared on the cover of Mountain magazine in 1986, climbers from around the world began to arrive. Nearly 40 years later, they haven’t stopped coming.

“Watts’ legacy is pushing climbing forward early on with a new style of route development that created the hardest routes of their time.”

“It was my dream to someday turn Smith Rock into an international climbing destination,” Watts says, but admits he didn’t anticipate the sheer numbers of climbers who would come or the impact they would have. “There are times when I’ve felt overwhelmed by the popularity, wishing I could step back in time to the old days.”

In the old days, Watts was often the only climber in the park. Those days are long gone. “I’m never lonely out there anymore,” he says.

We finally get past the conga line of adoring fans and find a shady wall that isn’t too crowded. Alan goes first. You wouldn’t know this compact, unassuming 63-year-old was one of the best rock climbers of his generation—until he starts climbing. He leads methodically upward, casually clinging to the pebble-size nubbins and finger pockets, toeing in on rounded edges worn down by decades of ascents. He makes quick work of the pitch.

Some people assume Alan is the famous Zen philosopher and writer of the same name. “There are serious climbers who think we are one and the same,” he says. “I used to remind people that the other Alan Watts died in 1973, but now…” Now he just suppresses that wry smile of his and says, “Ah, yes, in each of my books lies the seeds of my next book.”

Passing climbers ask Alan when the new edition of his guidebook will be done. “Soon,” he assures them, but admits it’s a bigger task than he imagined. “People keep putting up new routes,” he explains. “I have to get them all in.”

New Guide, New Routes

Rock Climbing Oregon’s Smith Rock State Park: A Comprehensive Guide to More Than 2,200 Routes, which comes out in August, has more than 800 new routes; it took three years of hard work—frustrating at times Watts admits, but fulfilling. “I had doubts along the way whether I had another guidebook left in me,” he confides, “but I somehow reached the finish line.” He credits the book with giving him purpose and preserving his sanity during the COVID pandemic. He’s clearly relieved to be finally done.

We only get in a couple of routes before Alan goes off to lead a history tour of the park, narrating as he goes, pointing out the hard climbs he and his contemporaries—local climbers and foreign hotshots—did in the ‘80s and ‘90s, which still rank among the hardest climbs anywhere. Despite the heat, the group—mostly younger climbers—eagerly follows, soaking it all in. Alan is clearly enjoying himself, proud that he’s able to share the place he loves most.

“I never could have imagined decades ago that climbers who weren’t even born at the time would be just as enthused about Smith climbing as I was when I was young,” Watts tells the group. “What happened at Smith Rock in the 1980s still matters.”

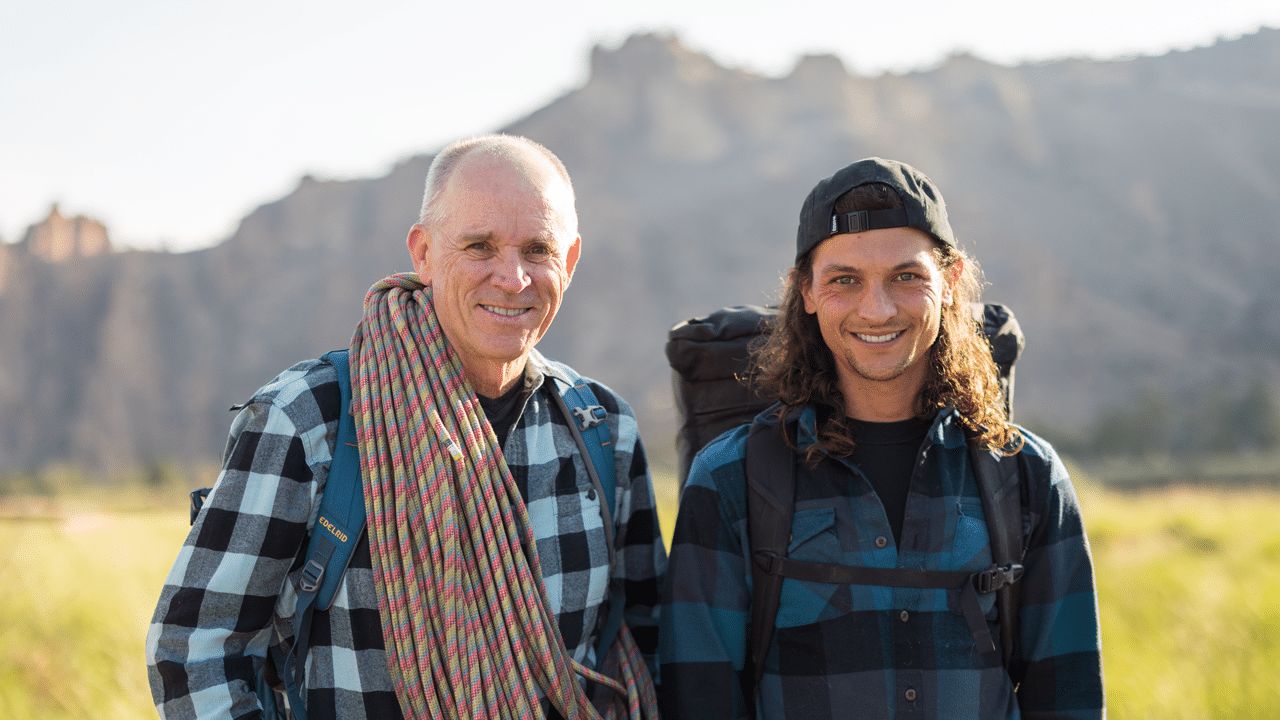

Watts wasn’t thinking of future generations of climbers back then; he was focused on climbing challenging new routes. But his single-minded obsession created a legacy, a torch that he’s passed on to a new generation, including Alan Collins, who, like Watts, is a passionate route developer who’s committed to preserving the character of the landscape.

“Alan [Collins]’s been a tremendous steward of the area,” Watts says. “In terms of new route development, he’s holding the torch right now.”

“I’m really proud to hear that he thinks I’ve got the torch,” Alan Collins says. “I’m just doing my thing out there.”

Collins, a 31-year-old Bend native, is one of the current driving forces of Smith Rock climbing. Since he started climbing seriously at age 19, he’s spent countless days establishing routes and building trails just outside the park boundary, developing new areas to help alleviate overcrowding in the park. Although some remain critical of the development process—removing loose rock and drilling protection bolts—it’s work he’s proud of. “I like things to look good, especially if it’s one of my routes.”

He’s quick to acknowledge Watts’ influence on the new generation of Smith Rock climbers. “Watts’ legacy is pushing climbing forward early on with a new style of route development that created the hardest routes of their time,” Collins says. “It’s always inspiring to think about everything Watts did back in the day. As a route developer, I have the utmost respect for Alan staying true to his vision regardless of the criticism.”

Is the future of Smith Rock climbing in good hands? Watts thinks so, but insists preserving the legacy of climbing here isn’t about one or two people. He credits organizations such as the Smith Rock Group and the High Desert Climbers Alliance for their access and conservation efforts, and Park Manager Matt Davey for doing a good job balancing access and overcrowding. He worries that increased bureaucracy may negatively impact the future of climbing in the park.

“It has taken the collective efforts of many people to keep this place from getting trampled to death,” Davey acknowledges. “For the first time, climbing is no longer purely in the hands of climbers.” He points to the draft master plan for Smith Rock issued in April 2023, which proposes the hiring of a climbing ranger to enforce climbing standards in the park and an online reservation and permitting system to alleviate overcrowding.

“I hope I never see the day when it’s necessary to make a reservation to climb at Smith,” Watts says, knowing it’s already happening at other climbing areas.

Regardless of new regulations, Watts believes older climbers—such as his role models from back in the day who helped shape his approach to climbing—play a vital role in preserving the legacy of climbing at Smith Rock. He says that the best way to assure access is for climbers to take it upon themselves to be good stewards and set a good example for newcomers to the sport.

“The older climbers not only inspired me but helped me define the boundary between what was and wasn’t acceptable,” Watts says. “Now I’m one of the older climbers who plays that vital role.”

Belay On

At any level, climbing requires diligent attention and support. Start with local companies and guides, such as: