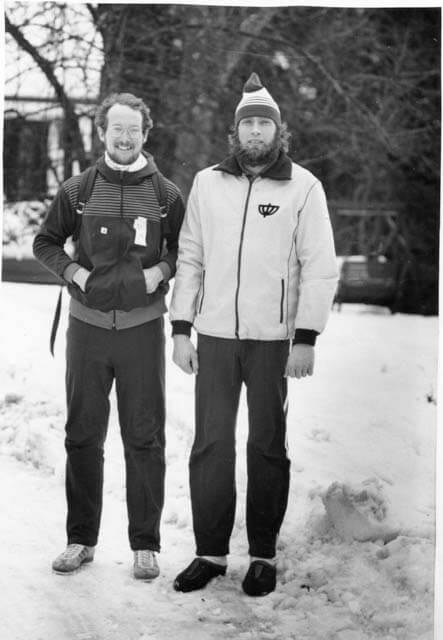

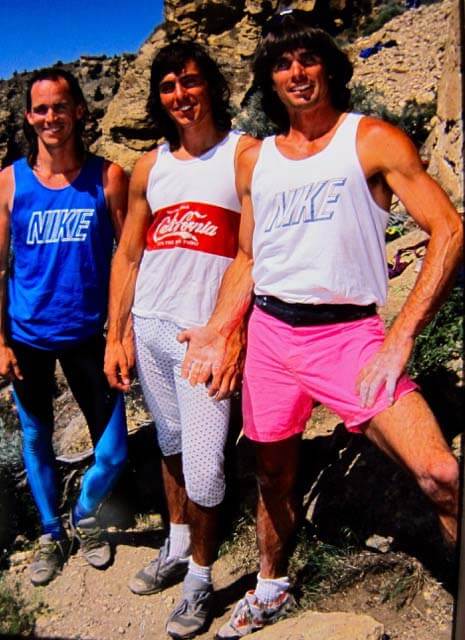

The gear, inelegant. The methods, crude. The hair, long. The pants, flared. The fun – full tilt. Bend’s “outdoor pioneers” transformed a region that would draw people from around the world with a thirst to explore the new. They were the founders of fun, Central Oregon’s original trailblazers.

Written by Cathy Carroll and Eric Flowers

When it comes to describing Bend’s outdoor recreation, the world has nearly exhausted the superlatives. The trails, rivers, lakes and mountain slopes fuel the area’s rapid population growth and an economy supported by a half-billion dollars in annual tourism spending. While this may be a year-round playground, it was once just a working town with a view. Whether you’re a weekend warrior or a die-hard adrenaline junkie, you have others to thank for blazing the literal and proverbial trails that now define our region.

Our Outdoor Pioneers are still outside doing nearly every activity they founded decades ago, so if you run into them on the trails or at a local watering hole, say thanks and buy them a round. We owe them one.

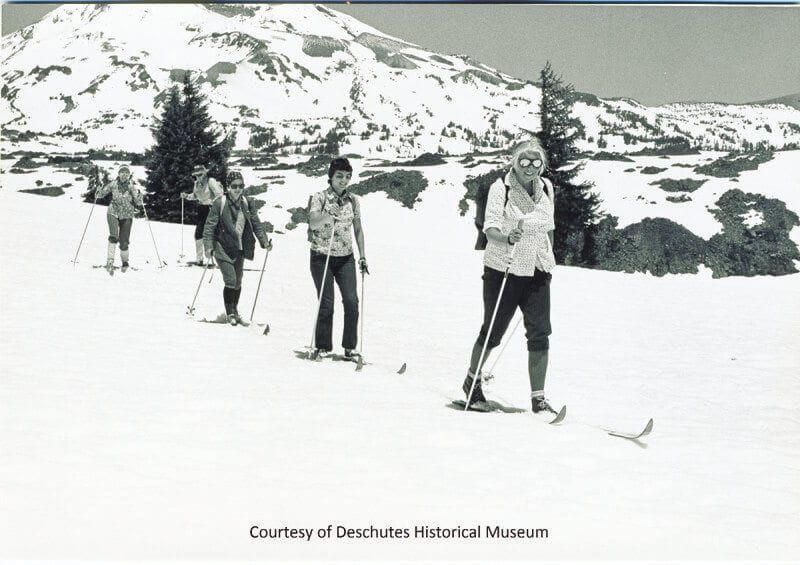

Nordic Skiing at Mt. Bachelor

Native Minnesotan Bob Mathews had stayed on at St. Cloud State College through the Vietnam War, and with a degree in history, didn’t know what he wanted to do this life, so he hit the road. While helping some of his high school buddies move to Bend to work at Mt. Bachelor, he got a job teaching cross-country skiing there.

“Cross-country was an afterthought at that time, so I went to Bill (Healy, a co-founder of the Mt. Bachelor ski area) to make something out of it,” said Mathews. “I typed a one-page proposal, and he said, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’ It was the right time and the right place, and he was an incredible guy to work for.”

That was in 1976, when there was just one small loop for cross-country skiing, and Mathews proposed a Nordic ski school separate from Mt. Bachelor’s alpine ski school. Mt. Bachelor began grooming a few cross-country skiing trails using one of its first snowmobiles. Just like that, the Mt. Bachelor Nordic Center was born, rooted in the spirit of camaraderie from a simpler, bygone era.

“Most of the people who worked up there were—I don’t know—ski bums,” said Mathews. “They hadn’t gone to college for ski area management, so people did a lot of on-the-job training. They were there for the moment, and they liked to ski. It was a fun place to work, the whole industry was in an upswing.”

Nordic Ski Camps and Races

Mathews and Bob Woodward ran Nordic ski camps and races, drawing hundreds of people. In 1978, the year Woodward had moved to Bend, he helped stage the Cascade Crest Marathon cross-country ski race from Mt. Bachelor to Little Lava Lake and back. Racers carried their own water with no aid stations in sight.

“It was a real wilderness cross-country race and spurred interest in long-distance racing,” said Woodward, “people showed up from Portland because it was the only groomed Nordic in the state. People went home saying Bachelor was a great place to go, and that Bend was cool.”

Woodward had moved to Bend two years after he and his wife, Eileen, had first visited and vowed to make the small logging town with a population of less than 18,000 their home. Working as a freelance sports writer and photographer, Woodward shared his passion for cross-country skiing by running a summer ski camp at Mt. Bachelor, a tradition he began during his first few months in Bend and carried on for the next fifteen years.

The geography-is-destiny quotient played out on a micro level as the Klister Korner gang, a group of Portland Avenue area denizens who took their nickname from a sticky cross-country ski wax, generated interest in Nordic skiing, mountain biking and whitewater kayaking.

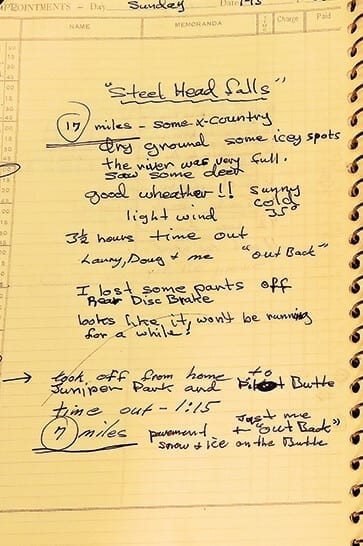

“It was natural synergy, with everybody loving and living to do all that stuff,” said Woodward. “We were exploring all the time, and there was always something new, someplace new to tour. Discovery was the key word, whether it was technique or things to do on the snow like snow camping.”

Designing Nordic Trails

As Mathews designed and cut out new Nordic trails, he paid homage to his compatriots, naming Oli’s Alley for Dennis Oliphant and Woody’s Way for Woodward. By the time Mathews left his position as director at the Nordic Center in 1992, the groomed trail network had expanded to fifty-six kilometers, with several hundred season-pass holders.

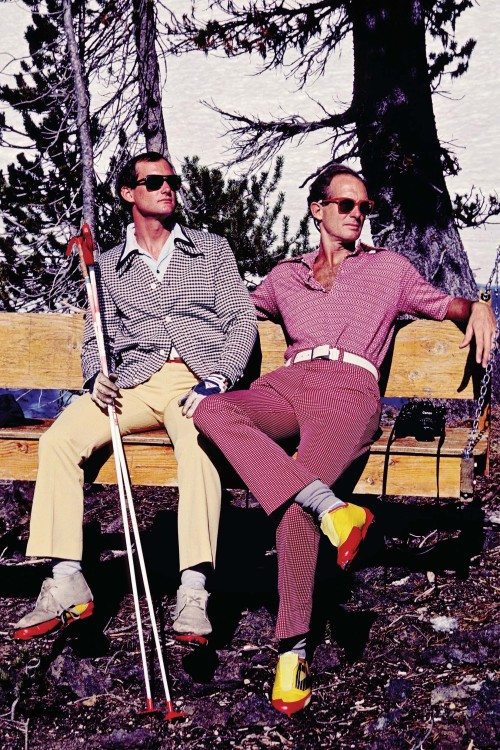

“There was a real sense of a little community that was building these sports, and it was the key to why it lasted,” said Woodward, who at 76 still skis and bikes frequently. “We got involved, stayed involved and spread it around. I’m tickled to death that there’s so much interest in Nordic. The only thing that bothers me is that people take it so seriously now. We had the dress-up days and kept a sense of humor about it at all times,” he said. “We’d get serious a few times for races, and the rest of the time was always about the fun and camaraderie. When I raced mountain bikes as the Reverend Lester Polyester and Art Deco, there were people in town who would call me Art–‘Hey Art, how you doing!’ There was nudging and winking a jaundiced eye for anything too serious–everybody was in on the gag.”

These modern-day enthusiasts were building on the earlier roots of cross-country skiing in Central Oregon, established by those such as Virginia Meissner, a mountaineer, and Bend’s Nordic first lady. She began teaching cross-country skiing at Mt. Bachelor when the ski area opened in 1958.

“They would have to go out and break a trail because they didn’t have grooming equipment back then,” said her daughter, Jane Meissner of Bend. “They had a first-generation snowmobile and would drag a sled behind them with two boards to make ski tracks.”

Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, Virginia Meissner taught cross-country skiing through Central Oregon Community College. She was known for her patience, encouragement, passion for sharing her love of the outdoors and for her perennially tan face. In the early ’70s, Meissner helped form the Central Oregon Nordic Club and served as its president, developing Nordic trails at Swampy Lakes, Dutchman Flat and Vista Butte. After Meissner died in 1988, the U.S. Forest Service named the Virginia Meissner Sno-Park in her memory.

Bend Mountain Biking

If there is a sport more firmly rooted in Bend’s DNA than mountain biking, it hasn’t yet been discovered. The sport has its international roots in Marin County, California, where bikers in the late ’60s and early ’70s were first experimenting with off-road riding. But Bend is the official birthplace of mountain biking in the Northwest, and the founders here needed no more inspiration than their own sense of exploration and some fat tires.

Before Central Oregon became a world-class mountain biking destination, there was Phil Meglasson riding forest roads and deer paths on a second-hand mountain bike he got at an auction in Fossil.

Phil Meglasson

This true pioneer of mountain biking in Central Oregon, along with his friends (including Bob Woodward and Dennis Heater) began riding the area’s forests and deserts at the dawn of mountain bike manufacturing in the early ’80s. Phil’s Trail was originally called Double-Cut Tree Trail, for a tree halfway up the canyon, but as mountain biking began to take hold and the area gained popularity, the U.S. Forest Service started referring to the area as “Phil’s,” and the name stuck.

In those days there were no signs. No maps. Meglasson and Heater, who founded the area’s first mountain bike fraternity, took old logging and forest service roads wherever they led, veering off on game trails that served as the precursor to what is now the area’s legendary singletrack.

Phil’s Trail in Bend

“That’s how Phil’s Trail got started,” Heater said. “We’d follow it as far as we could and then we’d start bushwhacking.” The intrepid pioneers cobbled together spare parts to turn a Schwinn cruiser into an off-road cycle. This typically meant new handlebars, motorcycle grips and oversized tires. The tools were inelegant. The methods were crude. (Heater remembers using a two-by-four to pry open the frame of his Schwinn to accommodate the new fat tires.)

“We could name everybody in Bend who had cycling shorts–and they were wool.” said Dennis Oliphant. If bike shops didn’t know what to make of these DIY “dirt bombers” as they referred to themselves, neither did anyone else, including the Forest Service, whose timberlands were quickly becoming the playground for the pioneering bikers.

“We wanted to go where no other bicycles had gone,” Heater said. “Back in the early days before the wilderness was closed (to bikes) we rode around the base of the Three Sisters in a single day. Talk about a gnarly ride.”

A Vietnam veteran with thick muscled arms, Heater grew up around Gilchrist riding his bike down gravel roads to reach fishing holes at Wickiup Reservoir. After losing his job in Southern California in the ’70s, Heater returned to Central Oregon. He started mountain biking shortly thereafter because he “couldn’t throw his motocross bike over a fence.”

A gregarious guy with a penchant for adventure, Heater organized group rides and off-road biking events around Central Oregon. He founded the Black Rock Club with a dozen other dirt bombers and a box of black T-shirts with no sleeves, printed with the club name.

“When it came to trails, it was Phil. When it came to fun it was Heater,” Woodward said.

The Grit of New Trails

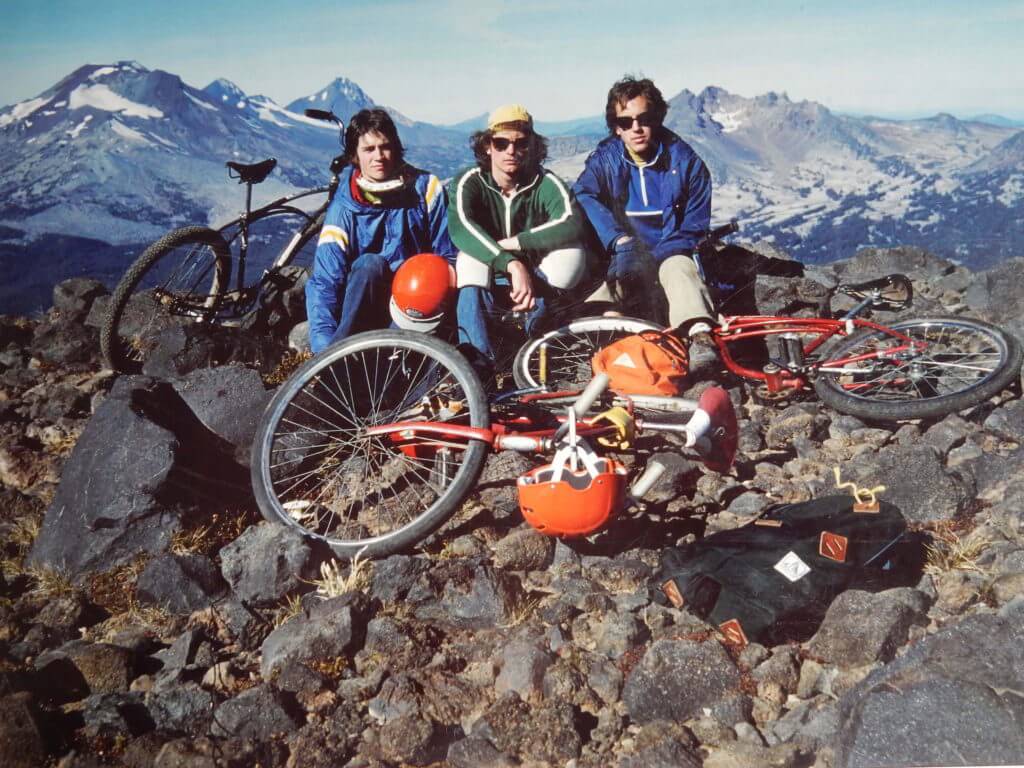

What the early adopters lacked in gear, they made up for in sheer grit. They rode Waldo Lake, made the first mountain bike trip up Burma Road Trail at Smith Rock and cut the heart of the trail system west of town. Other things were done, well, just because. That includes Gary Bonacker’s seminal descent of Mt. Bachelor with Tim Boyle and Don Ipock.

Armed with lightly modified cruiser bikes outfitted with coaster brakes, the trio hiked their steel frames up undeveloped summit slopes. It was October of 1976, nearly two decades before most people would even hear the term mountain biking.

A speed record may have been set, but never recorded. It was a different time. It wasn’t about conquering the mountain, it was about proving to themselves and maybe a few naysayers that it could be done. “Every one of the sports, it was uncharted water. It was new to here,” Woodward said.

Bonacker recalls training on Tumalo Mountain for the planned first descent of Mt. Bachelor. It wasn’t unusual for the group to run into the occasional hiker on the trail. At the time, the notion of bikes on sub-alpine trails was so unprecedented that the hikers would look at them as if they were from another planet. Bonacker and his merry band of bikers may have appeared fanatics and freaks to the outside world. But they never questioned the logic. “It was there. We needed to do it,” he said.

Closing in on 70 years old, Heater looks with awe at what the sport has become. From its humble beginnings, an entire industry and way of life that is now integral to Bend has grown. Dennis is still a regular trail rider, and the sport has a great future, in large part because of its storied past.

“I’m shocked that a few people have noticed that I was part of that gang that started it all,” he said. “And I think that’s a pretty good badge. I can’t think of another sport that I’d want to promote as much as mountain biking.”

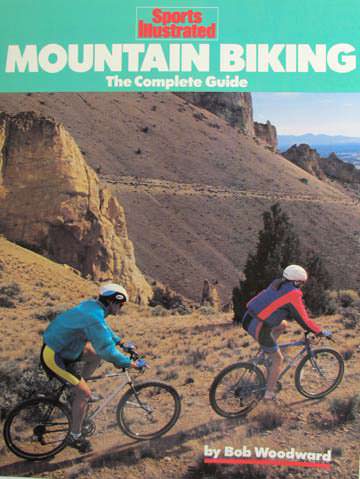

Read more about these same trails today. Our complete guide to mountain biking here.

Bend Whitewater Rafting

Look around today and signs of river culture are everywhere in Bend. The region’s primary export, Deschutes Beer, takes its name from the river that cuts through downtown. A newly minted whitewater play park opened this past fall–the crown jewel of a paddle trail that stretches from the high lakes around Mt. Bachelor to Bend.

It wasn’t always so.

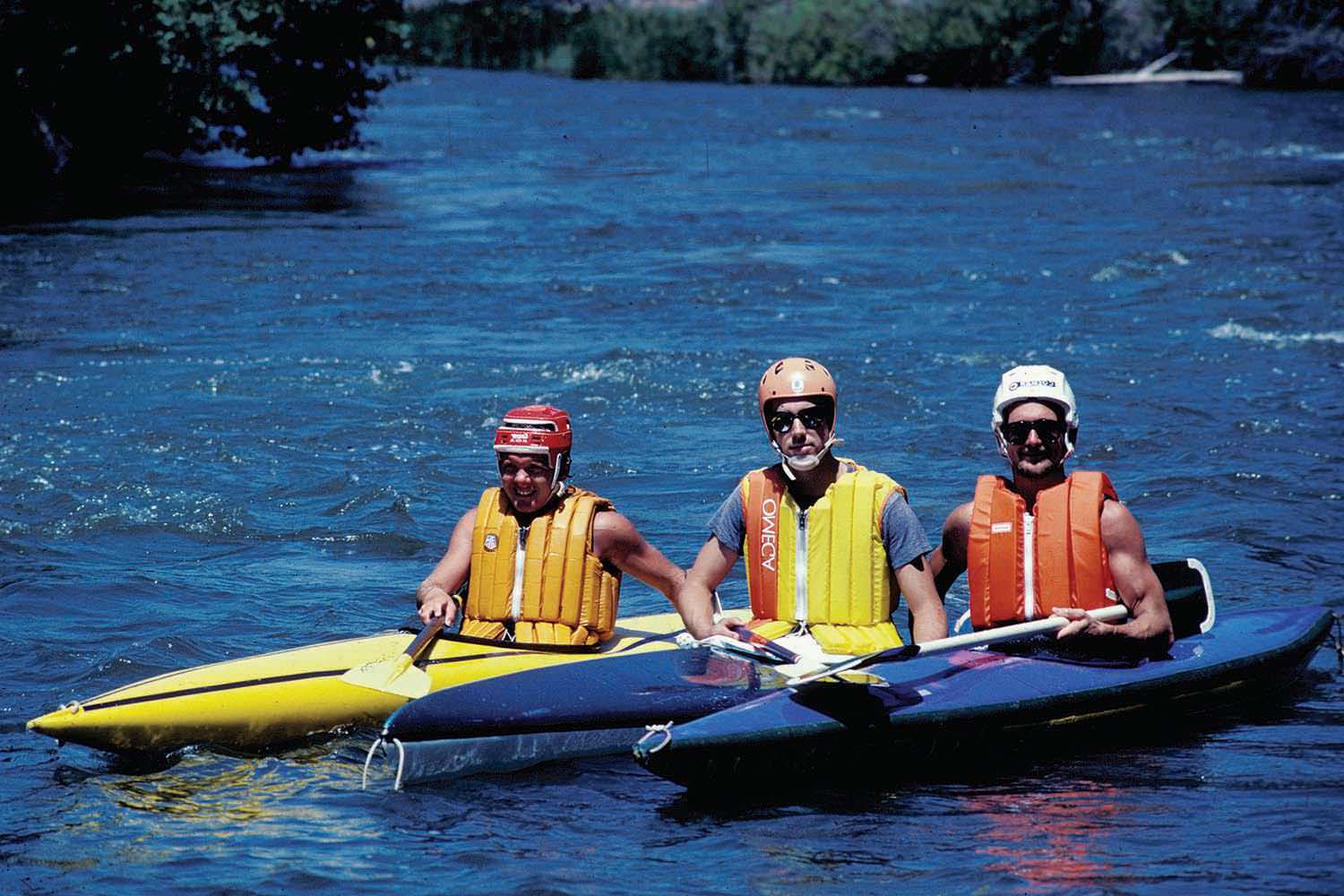

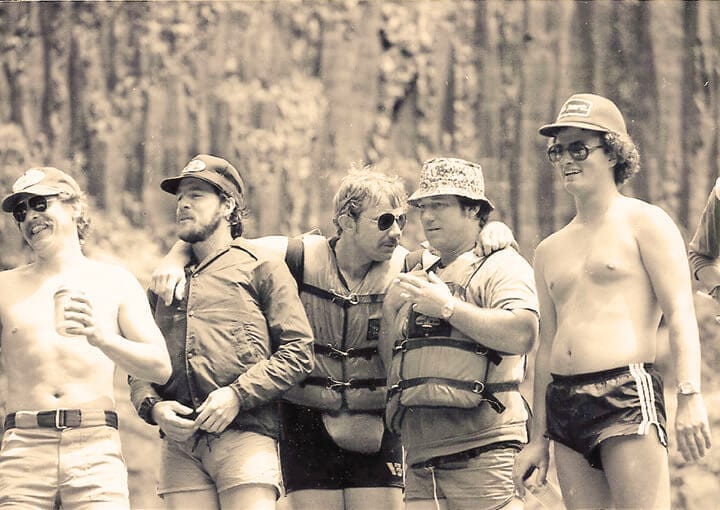

Back in the 1970s, the Deschutes River was still the lifeblood of agriculture and industry. Recreation was an afterthought. That all changed in the 1970s with the Klister Korner gang. The tightly knit group included Bob Woodward, Gary Bonacker and Dennis Oliphant who, together with a larger group of friends, started breaking down the boundaries. The approach was the same they would also take with mountain biking, substituting cheap kayaks and Army surplus rafts for their Schwinn Torpedos.

Together the group with its rotating cast of characters, including Woodward who had brought some whitewater experience and a passion for exploration, made the first kayak trips down the lower Crooked River, at that time a largely uncharted area filled with technical water and ever-changing obstacles thanks to its flood-and-drought regimen.

The group tamed Big Eddy, setting the stage for Oliphant to launch a rafting business out of the Inn of the Seventh Mountain (now Seventh Mountain Resort). He parlayed that into Sun Country Tours, the region’s premier river-guiding business.

Oliphant had arrived in Bend in the winter of 1977, fresh out of college at the University of Oregon, for a recreation management internship at the Inn of the Seventh Mountain. During that internship, Oliphant proposed and drafted a budget for a program to do rafting excursions on the Deschutes River. Commercial rafting was in its fledgling stage in those days. Cobbling together Army surplus rafts and learning from trial and error, Oliphant and the other program employees brought 4,000 people down the river that first summer.

“We certainly weren’t all-stars, but we were adventuresome enough and maybe a little crazy,” said Oliphant, whose company guided its millionth guest down the river last summer.

When Oliphant and his running mates weren’t guiding, they were exploring and pushing untested boundaries. As usual, Woodward wasn’t far from the action.

Home Base for Paddlers

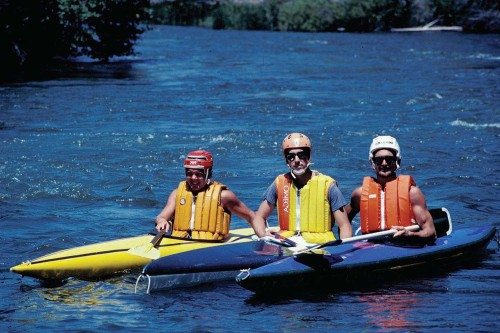

A reformed outdoor retailer-turned-adventure writer and photographer, Woodward used his industry contacts to wrangle at a super discount an entire truckload of Hollowform kayaks in 1979. They arrived on the back of a flatbed truck outside of Sunnyside Sports, one of only two shops on Bend’s west side and a gathering place for the area’s early outdoor adventure addicts.

Oliphant recalled hawking the novel, thirteen-foot (and one-inch) plastic boats around town. It didn’t take long for the idea to catch on. “It was like instant kayak community,” he said.

The group made their paddling home base at First Street Rapids, where Woodward taught Bonacker and others the basics, including how to roll a boat. “First Street was like a clubhouse,” said Bonacker, who sharpened his skills on the small wave that still attracts kayakers almost four decades later.

The First Documented Run of the Deschutes River

It wasn’t long before the ragtag group was adding more firsts to their growing list of outdoor exploits. Woodward and several others made the first documented nonstop run of the Deschutes from the Riverhouse to Tumalo State Park. It took two attempts and a small log removal project. Two weeks later, Oliphant would join them on the same run.

Soon they were venturing out of Central Oregon down the Klamath River, where they took on the expert-rated stretch below the John C. Boyle Dam at full high-water stage. It was on this stretch where Bonacker, who has lived twelve years with brain cancer and still bikes to work, had a near-death experience.

Bonacker recalls that he had attempted to “wet exit” his boat, dubbed “Fidel” for its brown, cigar-like profile, in a powerful eddy. Rather than slide out of the river’s hydraulic current as he had planned, he was recirculated. It ripped off his boat’s spray skirt–and his shoes. Unable to swim out, Bonacker was pulled down.

He remembers struggling, then, finally, relaxing. A single thought popped into his mind: the headline of tomorrow’s paper, “Bend Man Drowns.” It was then that he looked up and saw the white paint on the top of his boat. Energized, he struggled up through the current and poked his head into the inverted seat hole of the craft and the awaiting pocket of air. He was rewarded with his first breath in what felt like hours. Steadied, he maneuvered the upside-down boat out of the eddy to safety. The rest of the day brought multiple portages around the remaining rapids, and Bonacker’s nerves frayed.

His eyes are bright, soft and kind. His salt-and-pepper hair neatly combed. His skin is freshly tanned thanks to a two-week late winter stay in Baja, Mexico. His arms, however, are thin. He acknowledges that his kayak rolling days are over. Living with cancer for more than a decade, Bonacker has learned to accept some limitations even as he defies his doctors’ expectations.

Some of the risk-taking in his earlier years he chalks up to youth and ignorance. But he has no regrets. “If you start thinking about the “what ifs,” you’re probably done kayaking,” he quipped.

More than thirty years later, he’s still paddling, looking for the next adventure. Cancer be damned.

Read more about white water kayaking around Central Oregon today.

Rock Climbing at Smith Rock

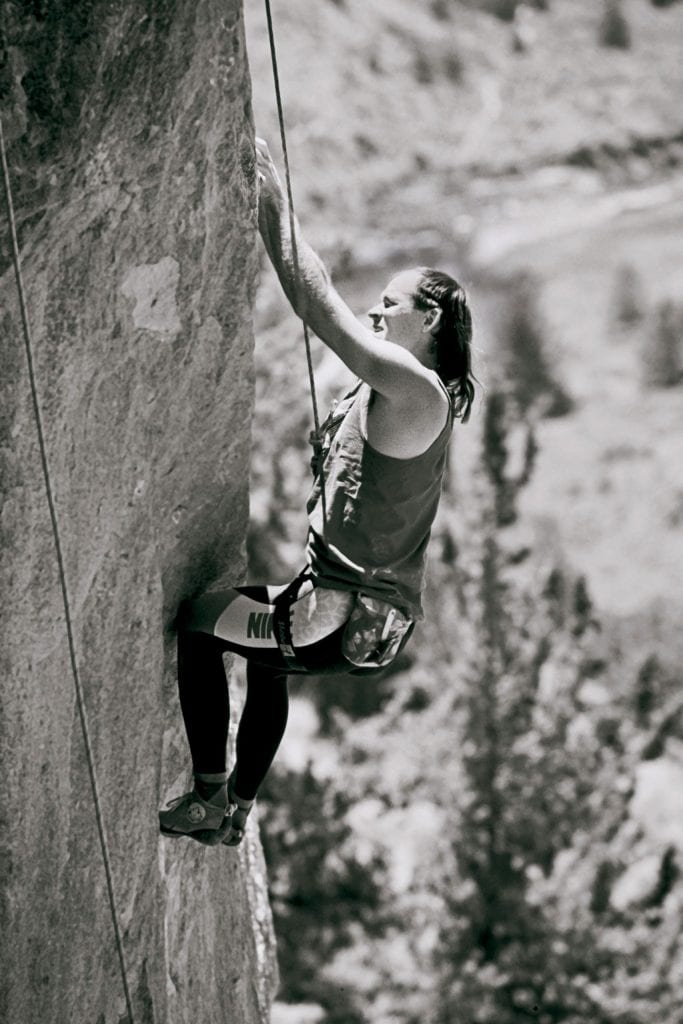

During the 1950s, Jack Watts and fellow Madras residents Jim and Jerry Ramsey started climbing at Smith Rock, putting up dozens of first ascents before it became a state park. Two decades later, Watts’ son, Alan, began climbing at age 14 with high school buddies. It was an inauspicious start to the birth of American sport climbing. Clad in the neon-colored lycra of the day, he–and Smith Rock’s standard-setting sheer canyon walls–would become world famous.

“The biggest obstacle I faced at the start was that almost no one climbed,” Watts said. “Developing the climbing at Smith Rock was not something that a young man should be doing with his life. My mom, in particular, was intensely concerned. Part of her concern was practical—I might very well kill myself pursuing my dream, but just as concerning for her was the fact that climbing wasn’t what normal young men did with their lives. Something must be wrong with me. Much like ski bums and surf bums, I was a climbing bum, more an outcast from society than a part of it.”

In 1979, traditional climbing was still the norm and sport climbing was controversial (people chopped off bolts in rock walls and got into fistfights). On top of this, Smith’s soft, crumbly volcanic rock is not the typical surface sought by climbers. Watts, however, having honed his rock climbing skills near Eugene during college, was drawn to the possibilities for the towering walls and textured spires.

“I spent so much time at Smith, I started noticing all of these unclimbed routes,” he said. “Almost everything done before 1980 followed a line up one of the natural crack systems splitting the walls. Once I started doing new routes at Smith Rock, it became apparent that traditional climbing tactics (used at Smith Rock and throughout the U.S.) wouldn’t work. I couldn’t just start from the ground and climb to the top. There was no way to protect myself in case I fell, and the rock was often dangerously loose.”

Rather than creating climbing routes from the ground up, Watts began bolting them by rappelling from the top of the wall to get a closer look at whether a route was possible, then drilling into the wall to place permanent bolts. Unbeknownst to Watts, this method of establishing climbing routes was catching on in Europe, but it was still relatively unheard of in the U.S. As a result, Watts took Smith Rock and American rock climbing to a new level.

Thanks to Watts, Smith Rock is now known as the birthplace of American sport climbing and attracts top climbers from all over the world. One classic route, Chain Reaction, became the most photographed route in the ’80s and helped spread the love for sport climbing around the globe. In 1986, the route To Bolt or Not to Be became America’s first 5.14 route and remains one of the hardest routes to this day. The origins of indoor climbing also can be traced to Smith Rock.

The Guidebook, Rock Climbing Smith Rock State Park

In 1992, Watts created the guidebook, Rock Climbing Smith Rock State Park, which endures as the premier rock climbing resource for the park. For him, the best moments were before the rest of the world discovered Smith Rock climbing.

“I wasn’t the only one who saw the potential of Smith Rock, and together we unlocked the potential,” he said. “At most there were a dozen of us, all living in Bend, who transformed Smith Rock into a world-class climbing area. The most fun came from hanging out with these incredible, inspiring, fun-loving individuals, sharing the dream. It became obvious after a few years that our approach was working tremendously well, and we knew that someday the rest of the climbing world would have to take notice.”

Watts was waiting in line at Jackson’s Corner in Bend a few months ago when he ran into an old friend and chatted for a moment until it was Watts’ turn to order. “In the background I quietly heard him mention to his female partner ‘He’s the one who developed climbing at Smith Rock.’ And I heard her quiet reply, ‘He must feel horrible about what he did.’”

When Watts goes to Smith Rock on a sunny day in peak season, and there’s no parking for a half-mile before the park entrance, he understands her point and shares her frustration. “But I recognize that I’m not to blame,” he said. “The discovery of the climbing potential at Smith Rock was inevitable. If I had never been born, someone else would have done the same thing.”

Through the Eyes of Alan Watts

But despite the massive growth throughout Central Oregon’s outdoor playgrounds, Watts considers the environment remarkably well preserved. “There are still days when you can be enjoying Nordic trails at Mt. Bachelor almost alone, or riding or running on Phil’s Trail when few other people are out there,” he said. “I still go to Smith Rock from time to time and find myself alone.”

Some areas have barely changed from the early days, he added. On a sunny day in August, hundreds of people will climb South Sister, while just a few will stand atop North Sister. “We are blessed with the vastness of our outdoor recreation options … each one of us has the responsibility to treat these special places kindly, so that future generations can enjoy the same experience as the pioneers.”

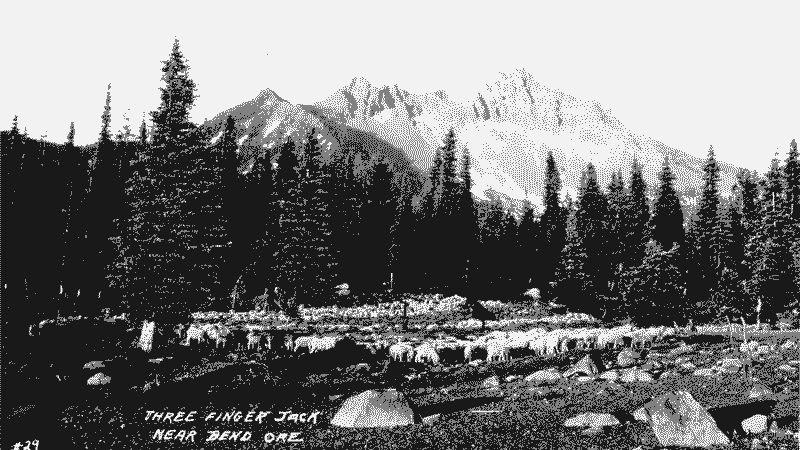

Photos From the Early Days of Bend’s Outdoor Scene: