The life and times of the storyteller, naturalist and namesake of Hosmer Lake, Paul Hosmer.

Paul Hosmer was a master of words. More than anyone else, he took the pulse of Bend’s millworkers and painted their tough world in vivid details. He was their champion.

Hosmer was an enigma. He was the scribe of the community but left a few cookie crumbs behind to explain his upbringing and life before moving to Bend, according to his son Jim Hosmer. Born in 1887 in St. Paul, Minnesota, Hosmer shared a glimpse of his formative years in a 1924 article in the 4L Magazine (The Loyal Legions of Loggers and Lumbermen). Hosmer told readers, “Received my diploma in football, baseball, basketball and spelling. Took a postgraduate course in boxing and had intentions of becoming lightweight champ.”

The spelling diploma presumably led him to newspapers “in half a dozen cities” before Hosmer ended up in Bend in 1915 working for the Shevlin-Hixon Lumber Company.

World War I put a hold on Hosmer’s career. Together with his good friend, Frank Prince, he enlisted in the 20th Engineers (Forest) Regiment. The outfit was designed to set up sawmills in France to provide building materials for the Allied forces. The two friends arrived in Europe in August 1918. Hosmer became a war stenographer, stationed away from the front lines. “After the armistice, I traveled around France playing banjo in a dance orchestra and made enough money to get into the crap games every night,” Hosmer wrote.

In the early ’20s after returning to Bend, Hosmer left the Shevlin-Hixon company and “moved across the river” to work for Brooks-Scanlon. One of his first jobs was to dream up the company newsletter that would define his life, Pine Echoes. Based on personal experiences, Hosmer told the stories of the workers at the mill and timber-fallers at the mill camps.

Hosmer’s articles also found their way into magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post and Oregon Motorist. In the 1930s, he shopped a story about Bend’s “Klondike Kate” Rockwell to the big Hollywood studios. Nothing came about, and the yarn eventually dreamed up by Tinseltown screenwriters for the 1943 film Klondike Kate had little to do with either “Aunt” Kate’s life or Hosmer’s script.

The lack of Hollywood success didn’t slow Hosmer, who remained a prolific writer and photographer throughout his years. It was Hosmer’s antics as much as his stories and images that imbued him with local celebrity status. Hosmer and his friend Prince were inseparable. Hosmer’s son Jim called them “the two roustabouts.”

“Frank had a lot of money, and dad had a lot of time and ideas, so they paired up and had all these escapades,” said Jim.

Like the time they lit a smoke bomb during a meeting at the Percy A. Stevens post of the American Legion and managed to keep the stunt a secret for several days. They were eventually hauled in front of the high court of the legion. The crowded hall was in full laughter throughout the proceedings. Although their defense strategy was built on an “insanity” plea of “temporary pyromania,” Hosmer and Prince were declared “guilty” of the crime and fined nominally for the prank.

Today, it’s hard to imagine just how isolated Bend was 100 years ago. Most of the culture was either homegrown or imported from family traditions. The mills attracted a large contingent of Scandinavian workers who had worked their way west in pursuit of timber jobs. Bend’s massive sawmills and the region’s extensive timber stock were a siren song for first and second-generation mill workers who came to Oregon from Minnesota and Wisconsin. (Both of Bend’s mills were owned by Minnesota-based companies.) Workers who came to Bend left behind extensive relations in the Midwest and abroad, but they brought along their passion for outdoor living—skiing during the winter and hiking and mountaineering all summer long. Eventually, they founded Bend’s ski club in 1927.

Hosmer came up with the name for the club, Skyliners. He also became the president of the club in 1929 and 1930. When Skyliners celebrated its ten-year anniversary in 1937, one of the founders, legendary cross-country skier Emil Nordeen, wrote that Hosmer was the “faithful pilot, without whose tireless effort the Skyliners’ dream could never have materialized.”

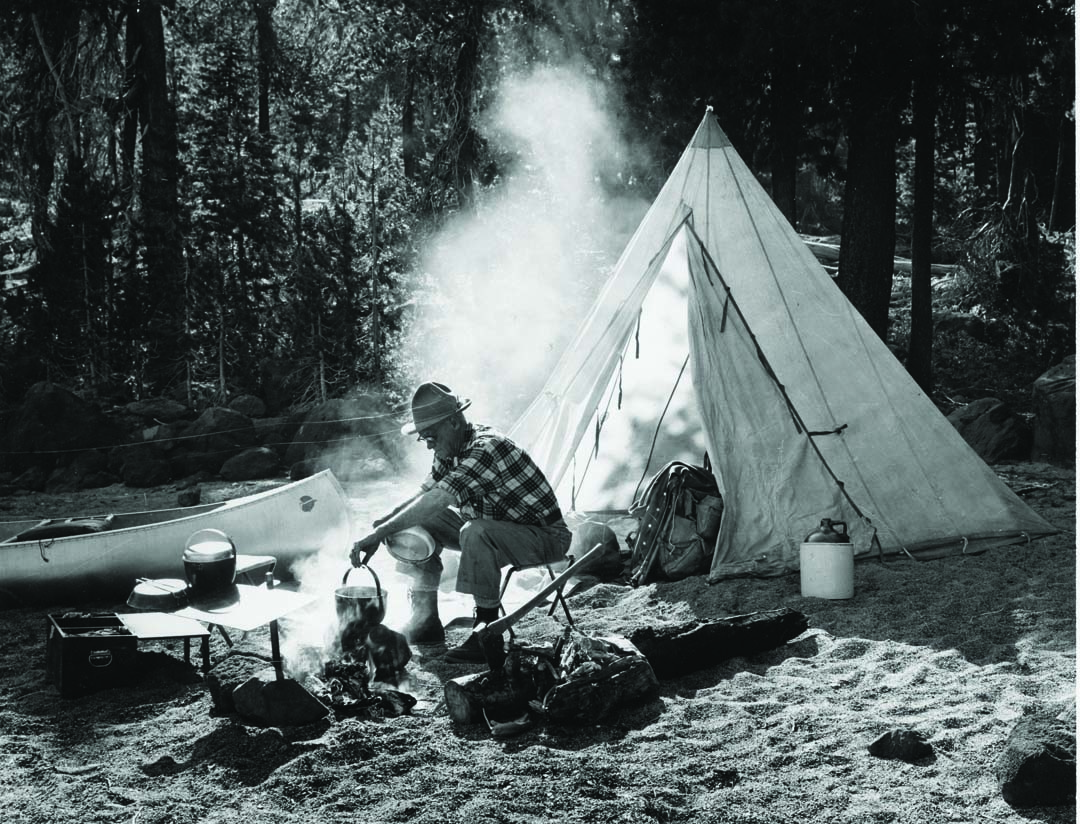

An amateur naturalist, Hosmer lived close to the outdoors throughout his life.

“His idea of having a good time was to walk into the woods with his canoe and paddles and go canoeing,” said Jim. In many ways, it is fitting he is the namesake of Hosmer Lake. Known previously as Mud Lake, it was renamed for him in 1962.

Hosmer retired from Brooks-Scanlon in 1961 after forty-one years as the editor of the Pine Echoes. He died a year later at the age of 74. One of the editorial writers for the Eugene Register-Guard, Bob Frazier, wrote, “the sage of the sagebrush country died last week.”