A mix of desperation and determination fueled Bill Smith and his enduring contributions to Central Oregon.

It’s approaching midnight on the Deschutes River and the scene is unusually quiet at the Brooks-Scanlon lumber mill. A workers’ strike has silenced the churning economic backbone of Bend, which, in 1973, supports many of the nearly 15,000 residents, directly or indirectly. The night watchman patrols the riverbank.

The river’s current is slackened by a dam and the banks have eroded from years of industrial activity. As the watchman goes, he snips off pieces of willow and pushes the tender shoots into the riparian mud, a minute reparatory act. The river’s surface, temporarily relieved of some of the logs that typically choke it, tempts him to drop in a fishing line, an act strictly forbidden on this liquid conveyor belt to the mill. Then it dawned on him: “I’m the night watchman; the only one who’d catch me is me.”

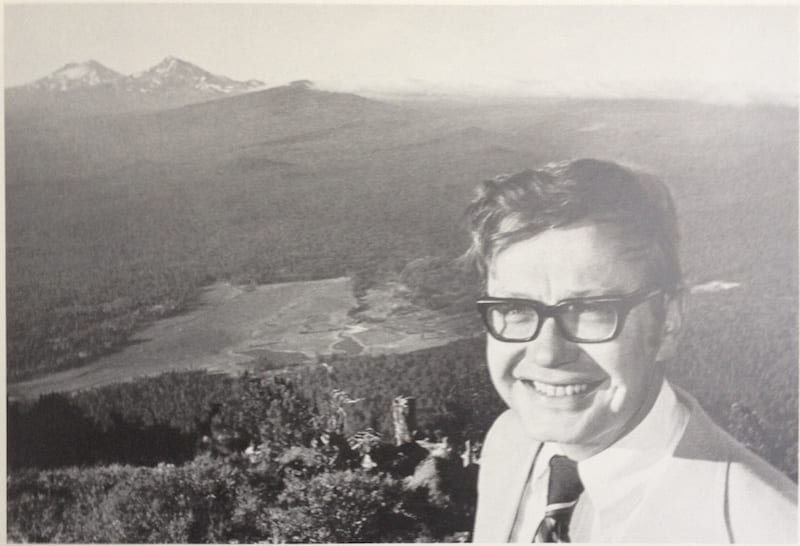

It wasn’t a job that William Smith was used to doing. Among the company’s top brass, he was pitching in to cover skeleton crew shifts during the work stoppage. The strike would end, but the problems were just beginning for the logging industry. Later that year, Smith would be named president of Brooks Resources Corp., the four-year-old real estate subsidiary of the timber monolith. He knew timber resources were limited; someday soon, the mill would close. But, boy, did he like that stretch of the river. Despite its industrial baggage, the site had potential. He wouldn’t have a chance to act on his notion, though, for two decades.

Fast forward to 1993, past an entire collapse of the Pacific Northwest timber industry, past Smith launching his own development company, and past a visit to San Antonio’s River Walk—where the shops, restaurants and public art lining the riverbank inspired him. Timber giants such as Crown Pacific and Weyerhaeuser are conducting fire sales on their timber holdings. Among those lands are several parcels bundled with the idle Bend sawmill, which most buyers considered the ugly stepchild in the portfolio. Smith, a consummate dealmaker, forms the River Bend Limited Partnership, and calls up the likely bidders with a proposal: buy the land and give him the unwanted mill, for a price. It didn’t take long for him to put together a deal.

It would take nearly five years—“four years, eleven months and two days,” Smith is quick to say—to funnel his plan through Oregon land use laws and get city zoning approval to begin creating the 270-acre Old Mill District. Central to that was cleaning up more than two-and-a-half miles of the riverbank that had been off-limits to the public for most of a century. The area opened in late 2000 with Regal Cinemas and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream shop as its flagship tenants. Today it has more than sixty businesses, including local and national restaurants, retail stores and nine historic buildings. The most iconic is the mill powerhouse, with its 200-foot-tall silver smokestacks, that now houses an REI store. A footbridge bedecked with colorful flags connects the shopping area to an outdoor amphitheater that hosts year-round events and attracts musicians on national and international touring circuits. Four hotels overlook the retail-lined streets and the walking and cycling paths that parallel the river and link to Bend’s extensive network of parks and trails. Thousands of people paddle or float by on this lazy section of the river, where otters frolic, offering evidence of the habitat’s restored integrity.

While the Old Mill District is Smith’s signature piece, and widely credited as integral to Bend’s rebirth, his prior work with Brooks Resources helped shape Central Oregon’s evolution from timber outpost to outdoor mecca. From Black Butte Ranch, Sisters and La Pine to major developments in Bend, such as Awbrey Butte and Mount Bachelor Village, Smith oversaw work that helped transform Brooks-Scanlon from a mill operator to a purveyor of destination lifestyles—work that helped rebrand and redefine the region in the process. He launched William Smith Properties in 1985, extending his holdings to vast ranches in Eastern Oregon. His wife and co-owner of the firm, Patricia “Trish” Smith, has taken the lead on their significant civic and philanthropic work, supporting arts and culture, education, and healthcare in Bend and throughout the state.

Known widely in the Central Oregon business community as a consummate dealmaker, Bill Smith turns 76 in August, with no intention of being more laissez-faire, even as the couple’s son and daughter assume responsibilities in the family’s thriving enterprises. By all accounts, including his own, it’s Smith’s pure love of work, ox-like persistence, obsession with detail and unrelenting desire to live nowhere but Bend that have allowed him to make a lasting mark on Central Oregon.

“Bill has cemented a place in our community’s history with his vision for the Old Mill District, whether you agree with his vision or not, and there are those in the community who didn’t necessarily want his vision,” said Kelly Cannon-Miller, executive director for the Deschutes County Historical Society. “It has had an undeniable impact on changing the face of Bend and what it means to visit here.”

Last summer, the Old Mill District was a finalist for the Urban Land Institute’s Global Award Program, alongside twenty-five others from Paris and Geneva to Manhattan and Mexico City, said Ken Kay, whose San Francisco-based design firm applied its specialty, linking urbanism and ecology, to Smith’s project.

Smith, known for his laconic style, sloughs it off. “It’s just fun,” he said. “I like to fix, rewind, repair, redo, rejuvenate. Historic preservation’s fun. Doing that gives you a place to know where you came from.”

The Making of a Dealmaker

You could argue that Smith pours so much into his work because he doesn’t know how to have fun. But it’s more complicated than that. The value of a day’s work was a notion embedded in him as a child. His maternal grandmother lived with his family when he was growing up, and she spoke with a heavy German accent. Trish recalled that the matriarch would sit in her rocking chair, always with a book, dispensing her favorite piece of advice: “You must verk.”

Smith, born in Denver to a mechanical engineer and a homemaker, the oldest boy of five children, launched a forty-hour-per-week lawn and garden business when he was a high school sophomore. He capitalized on the fact that the school was overcrowded. Half of the students, including Smith, had classes from 6 a.m. to noon, and the other half went until 5 p.m. Once he turned 16, he worked for his workaholic uncle’s growing trucking company, doing office work and filling in on the dock.

He graduated from the University of Colorado, Boulder in 1964 with a degree in economics, but the best employers avoided hiring men who might be drafted, so Smith joined the Navy. His four years of service included twenty-two months aboard a destroyer that bombed the shores of Vietnam, rescued pilots who’d been shot down and searched for those who missed aircraft carrier landings. In Saigon, as an Officer in Charge of Construction, he slogged through Agent Orange during the Tet Offensive.

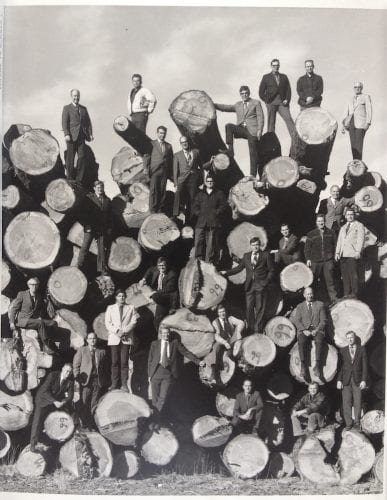

When he returned, he entered the MBA program at Stanford. In 1969, after Smith’s first year in the program, Mike Hollern, president of Brooks-Scanlon, recruited him and another graduate student to work for the lumber company during the summer, having interviewed about a dozen candidates. The company was founding its real estate subsidiary, Brooks Resources. That October, back in Palo Alto, Smith was at a party when a dark-haired, blue-eyed, fourth-grade schoolteacher walked in. He asked if he could buy her a beer. They were engaged at Christmas, married in June and moved to Bend in July 1970.

“Bill had turned down offers in L.A. and New York and chose Bend, where he could fish and hunt, which he did a bit, but not nearly as much as his imagination held,” said Trish.

Maverick Methods

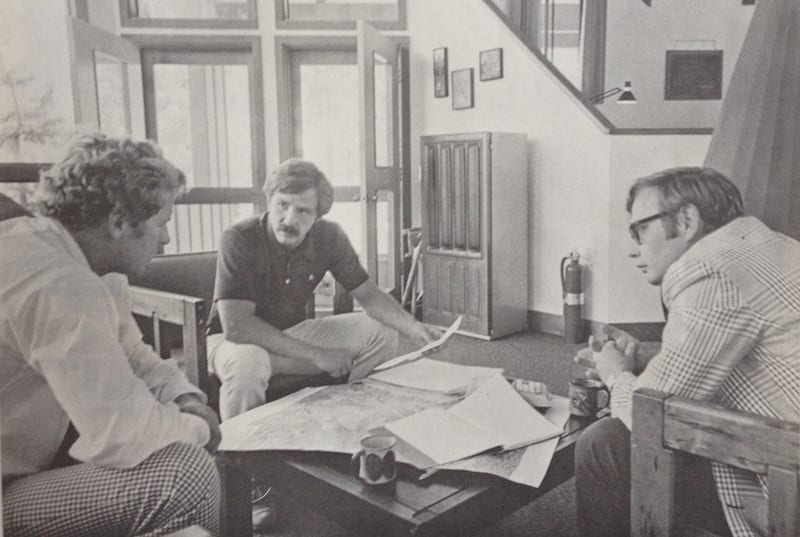

Newly formed Brooks Resources was creating Black Butte Ranch, and Hollern placed Smith in charge of marketing. Hollern recalled, “We did so many things differently—as young kids, we didn’t know any better—and I credit Bill with the marketing ideas: no paid advertising or print media.” Instead, Smith had frame-worthy posters made of Black Butte Ranch landscapes surrounding the undeveloped vacation home lots on 1,800 acres. He got the membership lists for all the private golf courses in Northern California, Oregon and Southern Washington.

“Every doctor, dentist, mortician, plane-owner,” Smith said, “anyone who made enough to afford a second home.” The vacation home concept had just arrived in Central Oregon with Sunriver and Inn at the Seventh Mountain (now Seventh Mountain Resort). The market research showed they could expect to sell about fifty lots at first. The Black Butte Ranch site had a natural advantage—people had to drive by it on their way to the other resorts, Smith said, “and they’d have gotten this unsolicited, nice piece. We didn’t have to spend as much to recruit them, we just had to get them to stop as they went by.”

Smith worked with a local designer and McCann Erickson ad agency in Portland to create the posters. The only information was a single slogan (which the property still uses): “There is a place … Black Butte Ranch.”

James Crowell, former communications director for Brooks-Scanlon, worked with Bill on the project. “Smith’s marketing approach was pure genius and set the tone for the way Brooks Resources sold property,” he said. “There was a very strict architectural review committee and they started with a limited number of lots to limit speculation. They wanted people to buy a lot, build a house and bring their family.”

It was a maverick approach for the 1970s, with the dawn of timeshares in Mexico and direct marketing brochures with price lists and huckster-like radio and TV pitches. “Real estate was being sold like used cars,” said Crowell. At a time when salespeople worked strictly on commission, Smith put his team on salary, which set them apart and kept aggressive pitching in check. “It was a heck of a different approach to selling property that nobody absolutely really needed,” said Crowell.

The team had sales objectives, though, and Monday breakfast meetings were important for the entire staff, not just salespeople. Smith reluctantly agreed they’d commence at 7 a.m. instead of 6:30 a.m. “He wound up every meeting with something I always thought was brilliant: ‘Nobody makes anything until somebody sells something,’” said Crowell. “Everyone loses track of that.”

Tough Times

Black Butte Ranch was the most fun because “success is always fun,” said Smith, but there were tough times, too. In 1982, while he was president of Brooks Resources, he led the company to invest heavily in Kennewick, Washington, piggybacking on the construction of a planned nuclear power plant. The gamble was ill-timed. The Washington Public Power Supply System was about to default on $2.25 billion in construction bonds for the project. It remains one of the one of the biggest municipal bond failures in U.S. history. WPPPS (dubbed WHOOPS by the national press) halted construction of several Pacific Northwest nuclear power plants, including one near Kennewick on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Speculators such as Brooks that bet on the accompanying boom had no recourse when the bottom dropped out of the local economy. Smith’s research on Kennewick had included several contingencies, but not an outright collapse. “I didn’t count on them hitting the pause button and there being no jobs,” he said.

The fallout was swift. Smith left Brooks Resources and began William Smith Properties with the ranchland that Brooks Resources didn’t want. It was precarious, and he admits now that he was afraid, but he had a plan: work even harder. “Instead of getting up at 4:30, I’d get up at 3:30.”

Hollern said, “He owed us a lot of money. We financed it, and he paid it off and we’ve maintained our friendship.” It took about six years for the market in Kennewick to turn around and Smith’s son, Matt Smith, now manages that region for William Smith Properties.

For all of Smith’s sheer love of dealmaking, positioning Bend for success in a new economy was central to the goal, and it aligned with his business philosophy: “If you’re doing good deals, you’ve got to have both sides win.” For him, that means a Bend where future generations can continue what he started. He still works every day, but when he isn’t at his desk with the resident cat, “Teeny,” he’s seen around the Old Mill’s wildflower beds with a couple of his five grandchildren, pulling weeds.

A Renaissance, Complete with a “Benign Dictator”

Trish, whose triple major included Renaissance history at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington and a year abroad in Florence, said, “I have a theory about Bend in the ’70s. It was a convergence of people who had a vision, like in Tuscany at the time of the Renaissance, and what they did lasted.” She cited Fred Boyle, a Harvard graduate who sought to model Central Oregon Community College after his alma mater; Mike Hollern, who came West to run Brooks-Scanlon even though the timber industry was dying; Sister Catherine Hellmann, a driving force behind St. Charles Hospital that spawned a regional medical complex; Rod Ray, who pioneered the area’s biotech sector with Bend Research; and John Gray, who created Sunriver, the area’s first destination resort, when “people didn’t know quite what it was,” she said. “All of the institutions in Bend we’re most proud of, the backbone, had those influences in the ’70s.” It created a foundation for today’s entrepreneurial tech and startup community, she said. “In some ways, it’s another Renaissance.”

A true renaissance also goes beyond brilliant, fresh ideas to compassion, and Trish has made that her life’s work. Since serving on Oregon Public Broadcasting’s board twenty-two years ago, she has become a primary source for philanthropic work east of the Cascades. She’s served on the board of many nonprofits, including: Oregon Health and Science University, Oregon Medical Board, Central Oregon Community College Foundation, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board (which distributes a portion of state lottery funds for salmon recovery, watershed improvement and state parks), St. Francis of Assisi Church and its school foundation and the Oregon Community Foundation.

Evoking the Renaissance, Smith refers to himself as the “benign dictator” of the Old Mill District, only half-jokingly. Clad in his unofficial uniform of blazer, Oxford shirt, striped tie and khakis, he removes posters and flyers which violate the Old Mill’s strict CCRs. He picks up litter, compulsively. His family recalls taking walks at Black Butte Ranch during its early days. They’d always have a Safeway bag with them for collecting litter. It’s a small act, but indicative of what has permeated all aspects of his business: a commitment to excellence. From his insistence on landscaping with flowers (another influence of his German grandmother and mother) to paying tribute to Bend’s history with pithy epitaphs on plaques throughout, to sending memorial gifts to the families of anyone who ever worked at the mill, Smith’s vision has always encompassed the micro and the macro. Trish summed up his credo: “‘Pay attention to the details,’ he would say, ‘It’s what always makes something good.’”

Giving Back

Among Trish Smith’s many charitable activities, she has been deeply involved with the Oregon Community Foundation, where she sits on six committees.

The foundation holds a $1.8 billion endowment, composed of about 2,000 charitable funds created by Oregon individuals and families, including the Smiths. It is among the top ten wealthiest and most generous statewide community foundations in America. OCF awards more than $100 million in grants and scholarships to Oregon nonprofits, and local recipients have included the Tower Theatre, High Desert Museum, Boys and Girls Clubs of Bend, Bethlehem Inn, KIDS Center and the La Pine Community Center.

“It’s ‘Oregon for good,’” Trish said. “We’ve touched every community.” OCF’s work ranges from the absolute essentials to the arts. She details how OCF made possible a symphony that took eighteen months to write and was performed on the rim of Crater Lake. In the next breath, the former schoolteacher rattles off statistics about the broader societal impacts of meeting the needs of children between birth and age three, that Oregon children’s dental health ranks near the bottom nationally, and that third-grade literacy is linked to school drop-out and juvenile justice rates. “We can move that needle,” she said. “Imbalance of opportunity directs your life one way or another, and if we can address it at an early age and solve problems, we can close prisons and open universities.”

Cheryl Puddy, an OCF program officer, said Trish Smith’s deep knowledge of Central and Eastern Oregon goes from the grassroots up to all stakeholders, on issues from schools to salmon to ranchers, and that’s just the beginning of what makes her an invaluable philanthropist. “‘Time, talent, and treasure,’ we always say—and Trish has all of those,” said Puddy. “I don’t know where she comes up with the time she devotes to all kinds of causes.”

Pingback:Paul Hosmer, The Bard of Bend — Bend Magazine