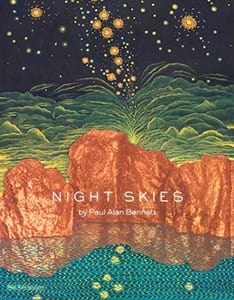

Sisters artist Paul Alan Bennett marries iconic desert landscapes to the heavens in a new book of works, Night Skies.

It’s 1986, and Paul Alan Bennett is driving alone around midnight toward the tiny town of Jordan Valley, near the Idaho border. He’s on the road through Paleolithic-age marshes, en route to rural schools as part of a state program to bring art lessons to remote communities. The headlights illuminate the path, with waves lapping over it from Malheur Lake, swollen with melting snow. The lake appeared endless, with nowhere to turn off the two lanes of asphalt.

“I just had to keep going, and I became so aware of the landscape and the power of it,” said Bennett. “I was amazed at how dark the sky can be and how many stars I could see. I found it spoke to me—driving off in the night sky—the sense of the scale of things.”

Although he was born in Montana, this was new to him. He came of age in Baltimore, went to the Maryland Institute of Art, and earned a master’s in Greek history at the University of LaVerne in Athens, Greece—places where the night sky is obscured by city lights and pollution.

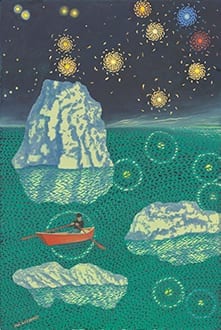

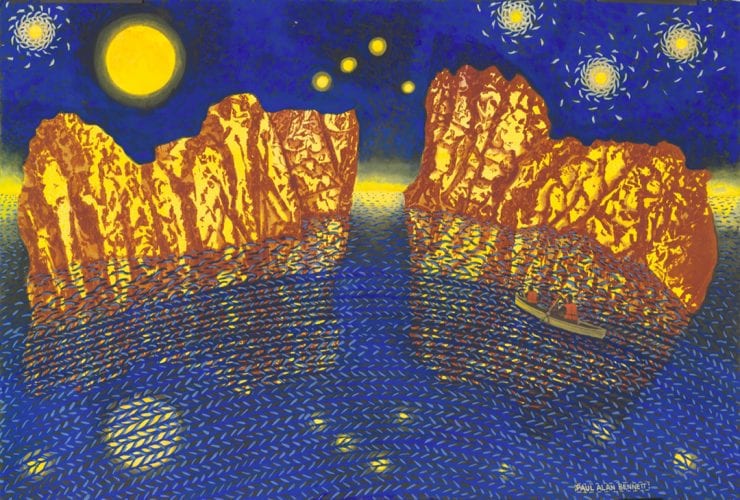

That night on the road not only inspired the first of scores of works about Earth’s celestial ceiling, but it also ignited his passion for stargazing, informed by the Greek mythology behind the constellations. Bennett wrote a play themed on the night sky and penned star-themed songs for ukulele. Most recently, he self-published the hardcover book Night Skies, which includes forty-four of his paintings. Employing his signature style, the look of knitted fabric created with watercolor, he depicts headlights projecting into the night beyond the blacktop, to a swirl of planetary splendor above.

That night on the road not only inspired the first of scores of works about Earth’s celestial ceiling, but it also ignited his passion for stargazing, informed by the Greek mythology behind the constellations. Bennett wrote a play themed on the night sky and penned star-themed songs for ukulele. Most recently, he self-published the hardcover book Night Skies, which includes forty-four of his paintings. Employing his signature style, the look of knitted fabric created with watercolor, he depicts headlights projecting into the night beyond the blacktop, to a swirl of planetary splendor above.

There’s a paddleboarder with a dog under a full moon and Virgo skies, a climber atop a Smith Rock spire beneath the constellation of Cygnus and a lone red car with beaming headlights joining the Corona Borealis, mythically formed when Dionysus tossed Ariadne’s wedding crown into the night sky.

Each illustration is accompanied by short bits of text such as:

“Look up. Feel the wonder and mystery above you.”

“Feel the moon welcoming your gaze.”

“Feel the night upon your skin.”

More Than A Muse

Yet the night sky is more than Bennett’s muse. He believes it’s a rich part of the human experience now largely ignored.

“That’s how people lived—watching the night sky—it was their Facebook,” he said. “That’s how they would navigate and know when to plant. For thousands of years we were connected [to] the night sky, but that’s not the case anymore.”

Bennett advocates for stargazing’s soothing, nurturing effects on the human brain.

Bennett advocates for stargazing’s soothing, nurturing effects on the human brain.

“It’s like a battery of wonder, to be connected and aware of this world, this spinning globe that we’re on and the swirling stars above,” he said. “When you get into negative thinking, or your brain gets stuck in the monkey mind, or maybe just being angry with yourself or thinking bad thoughts and you can’t seem to shake it, you’re in your head, and so the idea of looking at the stars is to get out of your head … getting people out of their computers, their phones and their heads.”

Just as people have embraced a Paleo diet, looking up seems to tap healthy benefits embedded in our DNA too, he said.

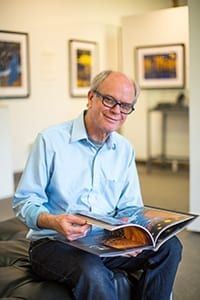

“I talked with people about the night skies and it’s almost always a personal, powerful experience,” said Bennett, 69. “It’s a time to connect with the bigger, vaster universe in which we live. It found a way into my work, and I found people really liked that.”

Free Show, Nightly

Central Oregon’s night sky is an asset as great as its mountains, rivers and trails, but doesn’t get as much attention.

“We live in a planetarium, and we have a free show here every night. Well, where’s the money in that?” he said.

Each evening, he looks up from his front porch in Sisters, where he’s lived since 1990 with his wife, Carolyn Platt, also an artist and teacher, and where they raised their son, Parker Bennett, now 27 and studying in Berlin.

“I don’t own a telescope, I just like standing on the front porch and seeing what I can see,” he said. “I like the feeling of vastness—nothing between my eye and the night sky.”

It’s his artistic eye that draws partners and gallery owners. Pendleton Woolen Mills created sixteen tapestries based on his images. People even wear his work, printed on leggings and dresses sold along with his book, original works, prints and cards on his website. Myrna Dow, owner of High Desert Frameworks, recalled discovering Bennett’s work shortly after opening her gallery in Sisters in 2001. One piece stood out to her.

“It featured the Owyhee River. To this day I love the colors, pattern and lyrical feeling of the river and surrounding land,” said Dow. “I knew right then that Paul was a wonderful artist with a unique style. at style is proven to be a very collectible characteristic that is loved by many.”