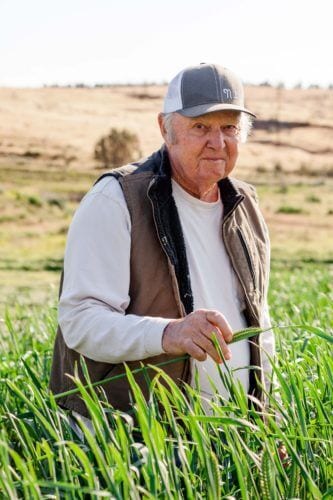

How Gordan Clark went from shaping surfboards in California to running Hay Creek Ranch in Madras.

The mid-’90s F-series outside Hay Creek Ranch’s shop has seen better days and covered many miles, but it saw a lot of freeway driving in its early days, said Gordon Clark. Because of that easy use, it has plenty of miles left for ranch chores that require the rig’s utility flatbed. A modest black-and-white logo on the front driver’s side quarter panel reads “Clark Foam,” and speaks to Clark’s first life that began decades before.

Clark’s first life was foam surfboard blank manufacturing in California where he pioneered the industrialization of modern surf board production.

The second life is playing out far away from the SoCal surf culture at Hay Creek Ranch on 52,500 contiguous Central Oregon acres, about ten miles due east of Madras. If you were to create a twenty-mile-long rectangle of property—roughly encompassing the city limits of both Bend and Redmond, it would need to be more than four miles wider to cover as much ground as the ranch. Of that, 720 acres are under irrigation. Clark and about a dozen hands run 4,000 sheep, 900 mother cows and all the equipment that supports the operation.

See the southeast horizon? That’s where the ranch ends. Beyond that? The Ochocos, where drovers will herd the sheep through leased summer pastures that extend the ranch well beyond its physical boundaries.

“Running a place like this is like piloting a battleship with an oar,” said Clark, 83.

Even though he is beyond the age where most people retire, Hay Creek Ranch is clearly no retirement job. The vast geographical scope of the operation provides a complement to a first career that was outsized in other ways.

“When I was young, all I wanted to do was surf,” said Clark. “I’d been building surfboards since I was a teenager.” It wasn’t long before he went to work for Hobie Alter, who had figured out a way to build surfboard cores from foam rather than balsa wood. In college, Clark majored in math and sciences, so he was a natural on the technical end.

The cores Clark helped create were sold to surfboard makers, who transformed them into finished, high-performance boards.

In 1961, Gordon “Grubby” Clark struck out on his own, building a factory in Laguna Niguel, California. He refined techniques for molding and reinforcing foam and his reputation grew as being the best in the business. By the start of the twenty-first century, industry experts estimated that Clark Foam supplied as much as 90 percent of the American market for blanks, and they said Clark may have supplied a majority of the global market. In 2002, Surfer Magazine placed him at No. 2 in its list of the “25 Most Powerful People in Surfing.”

In December 2005, he closed the factory without warning. Clark Foam’s market share plummeted to zero. In a seven-page fax to suppliers, he wrote that regulatory challenges—environmental, workplace and fire-related—gave him little choice in the matter. One line in the letter spoke to a reality affecting many American industries: “… You could build many blank making facilities outside the United States just for the cost of permits in California.”

A cowboy might call the resulting shock and confusion a goat rodeo. Nobody knew where the inner structure for new boards would come from. Mourning surfers, according to New Yorker writer William Finnegan, called it “Blank Monday.”

At the point of factory closure, Clark had already owned Hay Creek Ranch for a decade-and-a-half, and was living part of the year on the big island of Hawaii. He moved to the Oregon ranch for good in 2009.

Does Clark miss life on the beach?

“You’re only here once. I started surfing when I was real young. I did that—did the whole thing: a beachfront house, a surf break right out front,” said Clark. “Then I accidentally got into this thing, and it’s a whole new deal; it’s fascinating to do this.”

After decades of surfing and building boards, “I just feel fortunate to do something like this,” he said. “It’s like I’ve had two whole lives.”

Clark came to buy Hay Creek Ranch almost by accident. “Besides surfing all my life, I dirt biked all the time. A friend from Hawaii got the idea that we’d take a road bike trip,” said Clark. “So we saw the West that way.”

For bikers, the back roads of Eastern Oregon are heaven: next to no traffic, good asphalt, plenty of curves and a landscape that triggers a halt to one’s breath around each bend. Even the gravel roads are in good shape.

Before joining the bike crew on their ride through Oregon, Clark said a friend talked and talked about how amazing the riding was in Switzerland. After a stretch with curve after curve, fast descents, good climbs and stunning views, Clark pulled ahead, stopped his bike in the middle of the road, and dropped the kickstand. Climbing off and looking around in the silence, he asked: “What’s this you were saying about Switzerland?”

One of their rides took them past the ranch, which was a victim of the S&L crisis. The troubled insurance company holding the debt was receptive to fire-sale offers, and Clark was able to buy the ranch in 1993 with it in mind as a real estate investment.

Clark learned to guide his new “battleship,” as he calls it, from scratch. He imagined the neighbors’ initial thoughts: “Here comes this dork who doesn’t know anything.”

Any skepticism the neighbors might have had about a surfboard magnate may have been exacerbated by the fact he was the latest in a string of owners, spanning several decades, who had left things in a mess.

Clark got to work—part-time, initially—bringing things back up to snuff. He asked a lot of questions. “I’m not a farmer, and I’m not a rancher,” he said. “So I try to find people who know how to do it.”

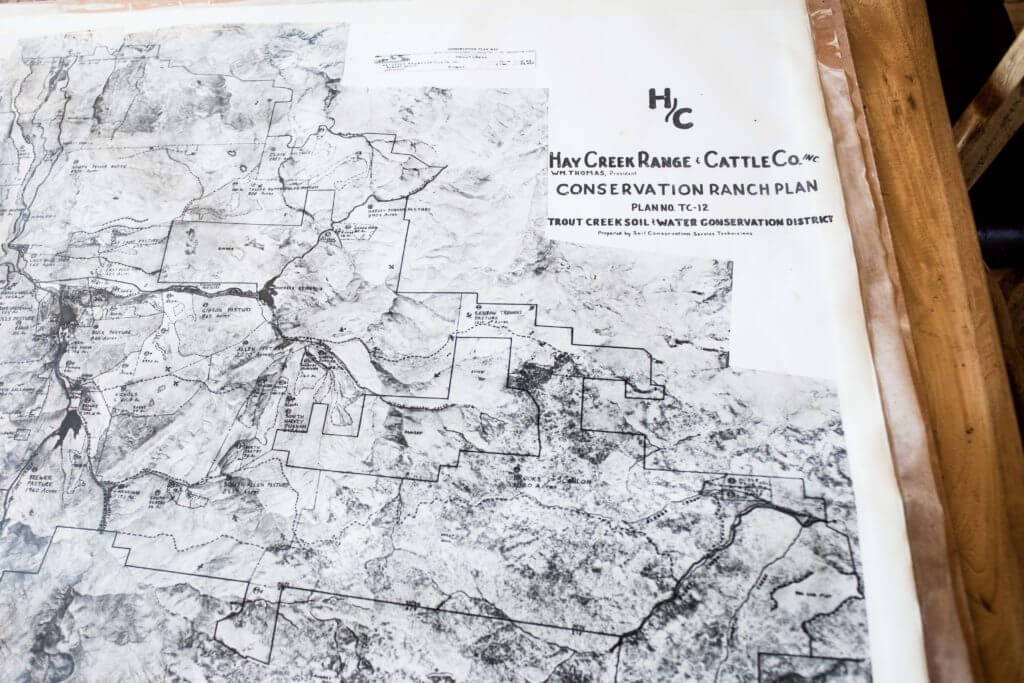

Hay Creek Ranch began in 1873 as the Baldwin Sheep and Land Company. At one time, the ranch ran 50,000 sheep (this was a time when plenty of open grazing stretched from the ranch down into northern Nevada) and created an economy large enough to support a village, complete with a store. A round barn, silo and large rectangular barn—all still in use—date back to the early 1900s. The main house is built around the ranch’s original cook house from 1910.

Today, the ranch employs about a dozen people full-time, including six sheepherders from Peru. It also employs high technology to support the best production practices possible. This comes with challenges similar to those of any factory. Just recently, Clark was in the field trying to figure out why a new tractor identical to one already on the ranch wouldn’t work with the swather harvesting hay for silage. Turns out it wasn’t identical: The PTO that makes the swather work spins in the opposite direction of the one on the other tractor. More troubleshooting.

Clark is obsessive about tracking and technology. Every animal has an ear tag with a chip that stores data about the animal; it’s all tracked in a computer system. Those self-driving cars you hear are coming our way? Tractors have that now, so even a rookie tractor driver goes in a straight line. He was so pleased with the system that, once when out on the tractor after dark, he impulsively turned off the headlights. Two reasons to not try this at home: Deer, while not caught in headlights, almost got run over—plus there was that section of wheel line that did get run over.

“I leave the headlights on now,” he said.

Clark gave a tour from the tight leather seats in the cab of his Ford Raptor, a high-performance short bed version of Ford’s classic F-150 work truck. The cab floor is littered with fast-food wrappers at the foot of the jump-seats. At the shop, he checked in on the progress of projects around the ranch and pointed out key pieces of equipment, including a twenty-nine-foot-wide swather and hay wagon that would bring the first cutting to silage pits over the next few days.

The silage pits are modeled after a design Clark learned about from a Dutch rancher: Concrete walls a little more than twice an average person’s height surround three sides of a rectangle about twice the size of a basketball court. As he explained the concept, a small crew wrestled with a huge tarp, intended to line the walls and cover the hay. Typical hay-cutting methods leave hay to dry on the ground where it is cut, then it is baled and stored for future use. Silage, instead, takes the green hay and encases it in sealed bins—sometimes plastic tubes—for storage. It requires an oxygen-free environment, hence the tarps. The process is tricky to do well, but storing the feed while it is moist preserves nutrients that would get lost in the drying process.

Clark drove into the concrete bunker and stepped out of the truck. “David,” he shouted. Turning back, Clark described David Auscheman, who oversees the sheep operation, as “one of the smartest guys I know. Tough. Feisty. Hard-working.” When Clark opened the half-door to the jump-seats, Auscheman pushed the wrappers aside and climbed in.

Hay Creek Road used to be what Clark called north-central Oregon’s “El Camino Real.” The Dalles to Prineville Stagecoach Road ran parallel to what is now Highway 97, and brought goods into and out of the area before the high bridges spanned the Crooked River Gorge at Terrebonne. It’s a well-maintained gravel road with no serious washboarding, but Clark hit the gas anyway. “It’s smoother when you go fast,” he said.

Clark headed north to Ashwood Road, turned right, then left and through a couple of gates into rangeland before decelerating in this slower world.

Sheep handed Clark the toughest learning curve at Hay Creek Ranch, and he said that he regularly travels hundreds of miles seeking advice. “It’s difficult to get information—not very many people do this,” he said.

In the distance, a familiar white shape was parked atop the ridge near where one of the three bands of sheep were grazing. The silhouette makes it clear that a traditional sheep wagon’s configuration hasn’t changed in a century and a half, though this wagon shows modern touches with a metal (rather than canvas) shroud and a solar panel. The back always points northwest to allow the sunrise alarm clock to shine through the front door. To the west is what would be a multi-million-dollar view for a real estate project.

“They always find the best view to park,” Clark said of his sheepherders.

Another quarter-mile up the road, 1,050 sheep and their lambs were clustered off the side of the dirt path. Great Pyrenees guard dogs and a herding dog greeted the truck. Back at the ranch house, the Pyrenees behave like 100-plus-pound lap dogs. Here, they keep coyotes away and their calm demeanor helps sheep feel secure. Their fur matches the sheeps’ wool, and they pack about as much dirt into their coats.

Over a period of several days, a herder takes a band of sheep from the wagon up the road to graze a new section of ground each day, going back to the area around the wagon at night. The choice of sheep breed, Rambouillet, was made in part because of their instincts to herd closely.

In the eighteen years since moving to Hay Creek from his home in the hills of Peru, Auscheman said that he and Clark have bounced a lot of ideas off each other. “We’re learning something all the time,” said Auscheman. “We talk a lot, ask a lot of questions.”

Over time, Clark and his hands asked enough questions and came up with enough ideas that Clark was named 2010 Livestockman of the Year by the Jefferson County Livestock Association.

This process of continually asking questions and coming up with ideas is shared by other successful ranchers.

“If you ever think you’ve got it down, you’re in the wrong business,” said Dan Carver. He and his wife Jeanie own Imperial Stock Ranch west of Shaniko, about thirty miles north of Clark’s ranch.

Sharing ideas is part of what Carver called “show-and-tell days” at farms and ranches where people are trying out new stuff. It’s also a matter of preservation. “We’re less than 1 percent of the population,” said Carver. “That makes it pretty important for us to talk with each other.”

Constant adaptation is part of that survival as well.

“These are changing times for sure,” continued Carver. “Climate change is a real thing. We say if we get two inches of rain in May, we’re off to a good start.” As of mid-May, he said there had been hardly any rain.

In discussing the ranch operation, Clark often used the term “factory.” He invokes the “Toyota Way” model for continual improvement and documentation of that improvement. He writes everything down, has much of the material translated into Spanish, and makes sure everyone follows the processes. If something breaks, they fix it and figure out how to keep it from breaking again. That reversed PTO on the tractor? He learned that there’s a checkbox on the order form to specify the rotation direction.

“One guy explained [to me] that ranching and farming is a series of small crises,” said Clark. “When something goes wrong, you try to fix it so it doesn’t happen again.”

If you drove east on B Street in Madras past the edge of town, kept going past the prison (don’t turn left), then continued on the dirt and gravel for a few miles, you’d see the first signs of the ranch: cattle fencing, downed junipers, occasional no-trespass signs that say Hay Creek Ranch or Centerfire Outfitters. At the crest of a long, easy slope, you’d sweep around a curve to see a lush green valley of hay, grain and lush pasture.

You could stop and look, but only if you parked on the shoulder. People sometimes drive fast because it’s smoother, you know. The sights you’d see are becoming less common. The challenges of passing on a family farm is a common theme in Midwest agriculture circles. Here, events such as the S&L crisis have some ranches changing hands regularly. The Big Muddy, just up the road? Thirty years after it was a commune for thousands of red-clad followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, it is now a Christian youth camp.

What’s the future for Hay Creek Ranch? Who’s going to take it over? Clark is adamant when the question is raised again late in the interview: “I won’t go there.” He did say that “If I get tired of the ranch, I’ll stop doing it.”

Clark, though, doesn’t seem tired of the ranch. “I really like it out here,” he said, and he definitely doesn’t find any time for sitting still. “Someone gave me a book recently. I’ve got a stack of fifteen books to read now.”

The systems for grass, grain, sheep, and cows that he and his workers have created continue to be developed and tweaked. Things break, things get fixed, then the solutions are put into writing. Whatever the future might hold for Hay Creek Ranch, at least there’ll be a manual waiting to be read.

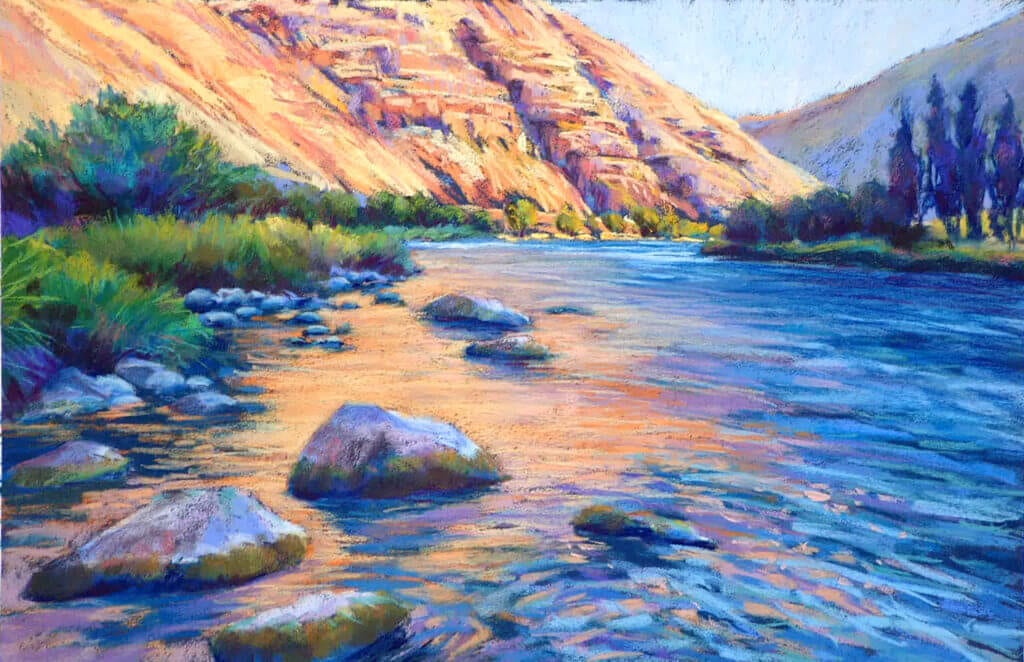

Wild & Scenic Crooked River

Wild & Scenic Crooked River

Combine the fickle weather of the Northwest with the predictable unpredictability of mountain climates and you have a recipe for snow in July and frost on the ground before October. This can make for, well, challenging conditions to enjoy the great outdoors. Add in a few kids and overworked parents, and you’ve got a recipe for a camping disaster. It’s probably no wonder that so many families have embraced a refined approach with the addition of travel trailers and, in some cases, motorhomes. But let’s get this out of the way: No one wants to saddle up next to a rig with a generator running outside their tent door or wake up with a forty-foot coach parked in what was previously a view of the evening sunset. That being so, there’s a time and place for trailers and motorhomes. Those who thumb their noses should try sleeping in a tent with a crying infant or spending a weekend huddled against an October winter storm with only a vinyl wall for insulation. Trust us. There’s a better way.

Combine the fickle weather of the Northwest with the predictable unpredictability of mountain climates and you have a recipe for snow in July and frost on the ground before October. This can make for, well, challenging conditions to enjoy the great outdoors. Add in a few kids and overworked parents, and you’ve got a recipe for a camping disaster. It’s probably no wonder that so many families have embraced a refined approach with the addition of travel trailers and, in some cases, motorhomes. But let’s get this out of the way: No one wants to saddle up next to a rig with a generator running outside their tent door or wake up with a forty-foot coach parked in what was previously a view of the evening sunset. That being so, there’s a time and place for trailers and motorhomes. Those who thumb their noses should try sleeping in a tent with a crying infant or spending a weekend huddled against an October winter storm with only a vinyl wall for insulation. Trust us. There’s a better way.

We may not have the peaks of Yosemite or the grizzlies of Glacier, but Central Oregon is a perfect launching point for countless backcountry camping adventures. From subalpine lakes ringing the Three Sisters to the novelty of paddle-in camping at Sparks Lake, there is a backcountry itinerary for anyone who has a passion for exploration. Here is a short list of overnight backcountry trips that offer a taste of what the region offers.

We may not have the peaks of Yosemite or the grizzlies of Glacier, but Central Oregon is a perfect launching point for countless backcountry camping adventures. From subalpine lakes ringing the Three Sisters to the novelty of paddle-in camping at Sparks Lake, there is a backcountry itinerary for anyone who has a passion for exploration. Here is a short list of overnight backcountry trips that offer a taste of what the region offers.